TIKAR PEOPLE: CAMEROON`S ARTISTIC BAMENDA GRASSFIELD TRIBE

The Tikar are a group of related ethnic proto-Bantoid Tikar-speaking groups in Cameroon. They live primarily in the northwestern part of the country, in the Northwest Province near the Nigerian border. In the Bamenda Grassfields, those who claim Tikar origin include Nso, Kom, Bum,Bafut, Oku, Mbiame, Wiya, Tang, War, Mbot, Mbem, Fungom, Weh, Mmen, Bamunka, Babungo, Bamessi, Bamessing, Bambalang, Bamali, Bafanji, Baba (Papiakum), Bangola, Big Babanki, Babanki Tungo, Nkwen, Bambili and Bambui.

Their population is approximately 47,000. They share their language with the Bedzan pygmies.

In recent times, the Tikar people have become popular to African-Americans.

Tikar people of Nso tribe, Cameroon

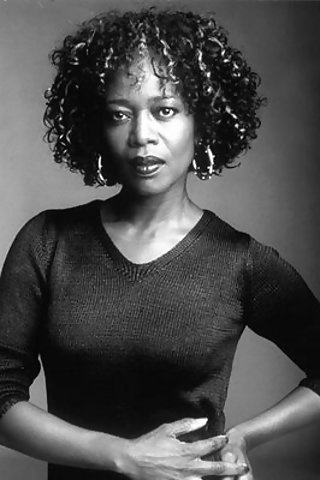

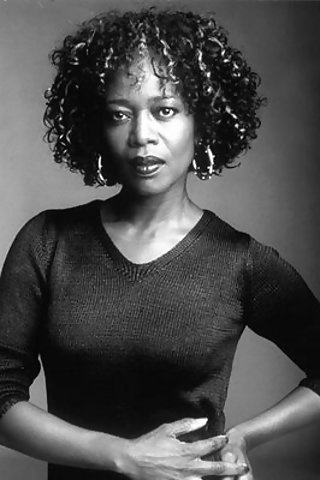

On the 2006 PBS television program African American Lives, the noted African American musician Quincy Jones had his DNA tested; the test showed him to be of Tikar descent. In the PBS television program Finding Your Roots, African American former Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice learned she shared maternal heritage with the Tikar. Actress Alfre Woodard's also traced her recent DNA ancestry to the Tikar people of Cameroon

Language

The Tikar people speak Bantoid language, also called Tikar. Tikar is a Bantoid language of uncertain classification spoken in Cameroon by the Bankim, Ngambe, and related Tikar peoples, as well as by the Bedzan Pygmies. Blench (2011) states that the little evidence available suggests that it is most closely related to the Mambiloid and Dakoid languages.Variants of the name are Tikali, Tikar-East, Tikari, Tingkala. A Bandobo variety (Ndobo, Ndob, Ndome) may be a separate language. Less divergent dialects are Twumwu (Tumu) in Bankim, Tige in Ngambe, Nditam, Kong, Mankim, Gambai, and Bedzan.

Tikar people

Tikar is a cover term for three relatively similar dialects spoken in the Cameroun Grassfields, Tikari, Tige

and Tumu (Stanley 1991). Tikar is spoken on the Tikar plain, south and south-east of Mambiloid proper,

and it shares a common border with some Mambila and Kwanja lects in Cameroun. The Tikar Plain, a

highly multi-lingual region, is referenced in many early administrative documents. Koelle (1954) includes a

Tikar wordlist, but the first analysis of the Tikar language may be in Westermann & Bryan (1952) who

considered it an isolated language. Richardson (1957) groups it with Bantoid and Williamson (1971) treats

it as an isolated subgroup of her Bantu node. Clearly, the Tikar language has always been somewhat

problematic in terms of its classification. Dieu & Renaud (1983) placed it together with Ndemli, another

language that is hard to classify, although this may be simply an admission of ignorance. Piron (1996,

III:628) recognises it as part of her non-Bantu group and assigns it a co-ordinate branch with Dakoid,

Tivoid, Grassfields and the other branches of Bantoid (her ‘South Bantoid’) in opposition to Mambiloid.

Stanley (1991) notes that Tikar has many lexical similarities with the neighbouring Bafia (A53) but that the

morphosyntax is quite different.

Legendary Musician Quincy Jones traces his ancestry to Tikar people of Cameroon

The main sources for this language are Hagège (1969), Jackson & Stanley (1977), Jackson (1980, 1984,

1987, 1988), Stanley (1982a,b,c; 1991) and Stanley-Thorne (1995). Following the establishment of a

literacy programme, Tikar has been studied intensively and there are various academic papers on the syntax

as well as a doctoral thesis (Stanley 1991). Separately a series of lexical studies published in German exist

(Mamadou 1981, 1984). There is also an unpublished lexicon (Jackson 1988). The Bankim dialect,

Twumwu, is the principal one chosen for standardisation and development. Nonetheless, primary

comparisons do suggest that Tikar plays a role in the North Bantoid grouping and it is tentatively assigned a

co-ordinate position with the Dakoid-Mambiloid grouping.

History/Origin

According to historians, anthropologists, archeologists and oral tradition, the Tikar originated from north-eastern Cameroon, around the Adamawa and Lake Chad regions(present-day Adamawa, North and Far-North Provinces). Tikar migration southwards and westwards probably intensified with the raid for slaves by invading Fulani from Northern Nigeria in the 18th and 19th centuries. However, there is reason to believe that such migration was ongoing for centuries long before the invasion. The pressure of invasion by the Fulani raiders certainly occasioned the movements that led the Tikar to their current locations in the Western Grassfields (Bamenda Plateau) and Eastern Grassfields (Fumban) and the Tikar plain of Bankim (Upper Mbam) (Mbuagbaw, Brain & Palmer, 1987:26; Mbaku 2005:10-12). Upon arrival in the Grassfields, the Tikar found other populations in place, populations which had either migrated from elsewhere or had

inhabited the region for centuries. Their arrival occasioned population movements, just as did the arrival of others after them. Pre-colonial Cameroon, like the rest of Africa, was richly characterized by population movements not always induced by conflict or invasion.

Tikar elders

In the Bamenda Grassfields, those who claim Tikar origin include Nso, Kom, Bum,Bafut, Oku, Mbiame, Wiya, Tang, War, Mbot, Mbem, Fungom, Weh, Mmen, Bamunka, Babungo, Bamessi, Bamessing, Bambalang, Bamali, Bafanji, Baba (Papiakum), Bangola, Big Babanki, Babanki Tungo, Nkwen, Bambili and Bambui. Their alleged migration from the Upper Mbam River region was in waves, and mostly led by princes of Rifum fons, desirous of setting up their own dynasties (Nkwi & Warnier 1982:16; Nkwi1987:15-28). The authors of A History of Cameroon capture the Tikar migration asfollows:

“It was about three hundred years ago that increasing pressure from the north and

internal troubles plus the desire for new lands led to the splitting up of Tikar

groups into small bands, which, having left Kimi, drifted further west and southwest.

Some of these moved under the leadership of the sons of a Tikar ruler who

later called themselves Fons, the most common Bamenda term for paramount

chiefs. These groups, at various times reached what is now Mezam. Among the

earlier were those who came from Ndobo to the Ndop plain in the south of

Bamenda, where they formed small, politically independent villages a few

kilometers apart. No semblance of political unity was achieved. In the north-east

we have Mbaw, Mbem, and Nsungli, also settlements of Tikar, and below the

escarpment of a later date settlements of Wiya, Tang, and War. The main body of

this group however, set off under the leadership of their Fon and founded the

kingdom of Bum. The Bafut, Kom, and Nsaw were among the last to arrive.”

(Mbuagbaw et al. 1987:30).

Tikar Structures and Institutions

The political structures and institutions of the Tikar chiefdoms are very similar, and have influenced and been influenced by those of neighbouring non-Tikar groups. Some useful studies of Tikar political structures and institutions exist. Like other communities in the region, a Bamenda Grassfields Tikar community is led by a chief who is popularly known as fon, and whose chiefdomhenceforth we are going to call fondom. The Tikar in the Bamenda Grassfields mostlycame as small princely emigrant groups, to occupy areas that were already settled by other groups, with the result that in almost every Tikar fondom, are smaller fondoms that were either conquered or given protection by the Tikar, but that have largely retained their hereditary dynasties (Nkwi 1987:23-30; Mbuagbaw et al. 1987:30; Warnier 1985).

African-American lady Anita Woodley who traced her root to Tikar being welcomed with an emotional hug by a Tikar women. She was renamed Bekang.

It is in this way that during the 19th century fondoms such as Nso, Kom, Bafut, Bum and Ndu expanded their boundaries by incorporating or making tributaries of neighbouring fondoms, while at the same time entertaining relations of conflict and tension or conviviality with their fellow Tikar fondoms. Bum, for instance, though small, gained importance from its role as an “entrepot for the kola trade with Jukun and Hausa in the

north-west during the later part of the century”, and had “intermittent hostility” with Kom, its southern neighbours, while maintaining friendship with Nso and Ndu. Nso was mostly at conflict with Ndu and enjoyed an alliance with Kom, which was in competition with Bafut on its south-western boundary for the allegiance of much smaller fondoms (Mbuagbaw et al. 1987:31; Nkwi 1987:23-30; Yenshu 2001).

Blair Underwood in Tikar dress. Despite his DNA ancestry being of Igbo origin some part of it also has Tikar traces. He is captured his visiting Tikar Village of Babunga (Vengo) in Cameroon

“The Tikar Problem” in the Bamenda Grassfields

Today, the various groups of Tikar now settled in the Bamenda Grassfields reportedly trace their origin to Tibati, Banyo, Kimi and Ndobo of north-east Cameroon. Indeed, many royal lineages of various Grassfields fondoms claim to have originated from the“Ndobo-Tikar” country, a region that covers the area between the Upper Mbam and the Upper Noun. In certain cases in the Bamenda Grassfields – Bafut, Nkwen, Bambili and Bambui, their claims to being Tikar are not backed up by traceable direct contact, rituals, exchange or fon linking them with Rifum or Bankim, the most prestigious centres of the Upper Mbam valley. Culturally, the only institution of Tikar origin in the fondoms in question is the princes’ fraternity known as Ngirri, which the fondoms of Nso and Bamum for example, claim they acquired along with the paraphernalia from Rifum.

Other institutions such as Kwifon (ngwerong in Nso and its tributaries) are widespread in the Grassfields and correspond to those in the Tikar groups of the Upper Mbam region. In terms of languages spoken, it would appear that the Tikar of the Grassfields have through encounters and conviviality with other languages over the years, lost much of their linguistic similarities with the language of the Tikar who presently occupy the Tikar Plain. Some would argue that this makes of the Tikar of the Tikar plain the “true” Tikar.

The lack of any direct connections with Rifum notwithstanding, the fondoms in question could well be of Tikar origin, just asthey could well not be. Nkwi and Warnier have observed, for some fondoms to have

maintained oral tradition to origin even with little to authenticate those origin, thosefondoms must have an interest in doing so, and those traditions must be significant in their life (Nkwi & Warnier 1982:26; Nkwi 1987:23-28). This issue has been termed by scholars “The Tikar Problem”, and remains the subject of much ongoing debate (Chilver & Kaberry 1971; Fowler & Zietlyn 1996: 6-15; Yenshu 2001).

To Jean-Pierre Warnier, an anthropologist and archeologist who has worked extensivelyon pre-colonial Bamenda Grassfields, in many regards, the “Tikar Complex” is essentially an affair of the relations between fons on the one hand, and between a fon and his people on the other. First, for fons sharing common claims of origin, the Tikar Complex was a sufficient basis in principle to establish mutual obligations and taboos in

an assumed alliance without the need for recourse to ad hoc rituals. And for fons who did not share the same myths of origin, the mere reference to Ndobo-Tikar was reason enough to establish difference as legitimate basis for hostility or to render necessary a ritual of alliance, or in other instances to fuel sentiments of aristocratic superiority on the part of a “Tikar” fon. The prestige that came with declaring oneself as Tikar even when one was truly not was the fact of being seen as brother of renowned fondoms such as Nso

and Fumban. With the claim to being Tikar came a certain sense of entitlement or legitimacy to power over non-Tikar populations even when these were in the majority.

Hence it must be stressed that Tikar traditions are first and foremost associated with royalty and royal lineages than with the wider group, and that acquiring either through payment or otherwise ‘authentic Tikar’ signs of legitimacy (e.g. regalia, Ngirri) directly from fons of Tikar descent was capable of bestowing some of that Tikarness on non-Tikar (Warnier 1985:264-266). Claims of Tikar origin mean less for most of the population than they do to their fons who seek political capital through such claims (Fowler & Zeitlyn 1996:6-15). This means that Tikar identity, like identities everywhere, is not only subject to renegotiation with new encounters, but that it cannot be understood divorced from the power dynamics that accord or deny value to identities.

The same argument is developed in Elements for a History of the Western Grassfields, which Jean-Pierre Warnier co-authored with another anthropologist, Paul Nkwi, a Tikar from the fondom of Kom. “Claiming a Tikar origin was tantamount to claiming high status and legitimate political power”, and the closer to Bankim in rituals one was, the greater one’s legitimacy and power. Thus the Bamoun, Nso and others, by recognizing

the ritual ascendancy of the fon of Bankim and by maintaining a tradition where newparamount fons must be blessed at Rifum, a sacred lake near Bankim, earn themselves enough symbolic capital to pull their political and economic weight vis-à-vis their own subjects who may or may not claim Tikar origin, and especially in relation to otherfondoms and the agents of the state who are constantly shopping for local authorities as

vote banks and auxiliaries of the government. Similarly, the further and further away from Kimi one got, the more remote and difficult to substantiate their claims to be Tikar became (Nkwi & Warnier 1982:26-27)

Given that the Bamenda Grassfields were occupied long before alleged Tikar migration, the fact that the royal lineage claims Tikar descent does not imply that the fondom as a whole is Tikar, as the situation of Bum and Bafut would attest (Nyamnjoh 1985; Yenshu 2001). Among groups where Tikar origin is claimed by both royal and commoner lineages are Kom, Nso, Mbem and Weh (Nkwi & Warnier 1982:14-16).

However, given how common it was for people to move between groups in the 19th century for reasons of

trade, witchcraft, conflict, diplomacy and marriage inter alia, it is hardly surprising that few Tikar groups were pure and that fewer still are, even where commoners and royal lineages continue to claim Tikar origin. It was and still is commonplace for potential successors to compete for the throne on the death of a fon, and for the unsuccessful candidates to take refuge in other fondoms, taking along with them large numbers of supporters (Nkwi & Warnier 1982:24-28; Nkwi 1987:23-28). Here as elsewhere, the tendency to trace descent exclusively through the male line has often had the effect of oversimplifying the complexity of identities. Personally, I grew up in two palaces and belong with at least three fondoms, two Tikar (Bum and Mmen), a third Widikum (Mankon), and my biological and social origin can be traced to a lot more, such that

answering simple and often simplistic questions such as ‘where do you come from originally?’ is no simple feat (Nyamnjoh 2002). There is therefore no such thing as the essential, pure or homogenous Tikar community even amongst the so-called “true” Tikar of the Upper Mbam Tikar Plain, just as there is no essential African or American, as long as physical, cultural and ideological mobility are part and parcel of our reality and history. Being Tikar, being American or being anything for that matter, is always a negotiated reality subject to constant renegotiation in tune with new encounters, the aspirations of the moment and the relationships that engender such aspirations and make possible or impossible their realization (Nyamnjoh 2002, 2005, 2007a&b).

Tikar people

Trading and Relations with Others

Prior to the 19th century the Grassfields were a largely isolated region. Given the high altitude, mountainous and difficult landscape of the Grassfields, the lack of navigable waterways, and the fact that transportation prior to the opening of motorable roads was largely done by human porterage, the region did not benefit from the vast trading networks that crossed Africa in various directions, and which coastal chiefdoms took

great advantage of. The mountain range that extends from the Grassfields to Lake Chadand the Jos Plateau of Nigeria remained largely undisturbed until the 19th century (Nkwi & Warnier 1982:78). Trade was mainly in slaves (see Chem-Langhëë 1995, for more on 19th and 20th century slavery in the Grassfields), ivory, kola nuts, salt, oil, iron, cloth pearls and cowries, which in certain regions were adopted as forms of payment. During the 19th century the Bamenda Grassfields was still very largely outside the trading networks of the Benue and Adamawa. But these two networks would spread themselves into the Bamenda Plateau at the end of the 19th Century, thereby offering the communities of the region the possibility for differentiation (Rowlands 1978; Warnier 1985:141-148).

Two Tikar fondoms, Bum and Fumban, occupied strategic positions as trade routes, Bum for trade with Wukari and Fumban for trade with Banyo. At first, trade between the Benue and the Grassfields was still mainly in the hands of the local population, which was not the case with trade with the Adamawa region, which was totally under the control of the Hausas, whose impact in the Grassfields has been such that there is hardlya local market today where one does not find a Hausa trader on a mat with items such as herbs, salt, powder and little packets of mixtures of cooking ingredients of all sorts. The mountainous nature of the region added to many rivers to make it difficult to travel, especially at the rainy season, meaning that only certain routes were possible for traders. Kola nut mostly produced in Nsungli and Nso was sold in Nigeria through Banyo, Yolaand Takum, and the importance of the Banyo route was only diminished when the French and British set up customs posts. The donkeys seen today in Nso (where they are called “the kola animals”) and elsewhere in the Grassfields were probably introduced during the kola trade (Warnier 1985:141-148). In the second half of the 19th century, the fon of Bafut was allegedly so powerful that he used to send traders as far away as Takum (Warnier 1985:267). The Western and Eastern Grassfields along with their Tikar fondoms have yielded some of the most enterprising entrepreneurs in present day Cameroon

(Warnier 1993).

Procession of Tikar elders

Culture

The Tikar have elements of matrilineal and patrilineal descent. Their folk belief states that during pregnancy the blood that the woman would normally release during menstruation forms parts of the fetus. This blood is said to form the skin, blood, flesh and most of the organs. The bones, brain, heart and teeth are believed to be formed from the father's sperm. In the case of a son the masculinity also comes from this. The Tikar are also noted as mask-makers.

The primary religion of the Tikar people is Islam

The History of the Masks of the Tikar

The Tikar people have focused on education for generations. Teachers taught boys vocational skills which included craft-making, woodcarving, mask carving and making bronze sculptures. They developed a process of using hot wax and bronze to create masks and statues to be used during agricultural ceremonies and festivals.

The Tikar or Twumwu people currently number between 44,000 and 250,000 (depending on the source) in Cameroon, in the grasslands areas of central Africa. More than 25 peoples of this area currently claim Tikar origin including the Nso, Kom, Bum and more. While they speak a variety of languages (even though French and English are their official languages), they all claim to have similar ancestors linking their history and culture. Approximately 65 percent of the population is Islam with another 20 percent claiming Christianity. A largely agricultural people, their main crops are cocoa, coffee, bananas, plantains, sugar cane and cassava, among many others.

Tikar Buffalo mask

Ceremonies

Many believe the Tikar masks are originally used to celebrate agricultural ceremonies or festivals with a plentiful harvest resulting in even larger, more elaborate celebrations. Hosting an honored guest was also cause for celebration as these extremely political people were wise to treat foreign dignitaries with respect. During these festival,s plam wine, billet beer and carbonated drinks are served along with a chicken, goat, steer or sheep.

Source:http://www.nyamnjoh.com/files/africanamerican_ancestry_search_tikar_origins.pdf

Their population is approximately 47,000. They share their language with the Bedzan pygmies.

In recent times, the Tikar people have become popular to African-Americans.

Tikar people of Nso tribe, Cameroon

On the 2006 PBS television program African American Lives, the noted African American musician Quincy Jones had his DNA tested; the test showed him to be of Tikar descent. In the PBS television program Finding Your Roots, African American former Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice learned she shared maternal heritage with the Tikar. Actress Alfre Woodard's also traced her recent DNA ancestry to the Tikar people of Cameroon

Condolezza Rice traces her ancestry to Tikat people of Cameroon

Language

The Tikar people speak Bantoid language, also called Tikar. Tikar is a Bantoid language of uncertain classification spoken in Cameroon by the Bankim, Ngambe, and related Tikar peoples, as well as by the Bedzan Pygmies. Blench (2011) states that the little evidence available suggests that it is most closely related to the Mambiloid and Dakoid languages.Variants of the name are Tikali, Tikar-East, Tikari, Tingkala. A Bandobo variety (Ndobo, Ndob, Ndome) may be a separate language. Less divergent dialects are Twumwu (Tumu) in Bankim, Tige in Ngambe, Nditam, Kong, Mankim, Gambai, and Bedzan.

Tikar people

Tikar is a cover term for three relatively similar dialects spoken in the Cameroun Grassfields, Tikari, Tige

and Tumu (Stanley 1991). Tikar is spoken on the Tikar plain, south and south-east of Mambiloid proper,

and it shares a common border with some Mambila and Kwanja lects in Cameroun. The Tikar Plain, a

highly multi-lingual region, is referenced in many early administrative documents. Koelle (1954) includes a

Tikar wordlist, but the first analysis of the Tikar language may be in Westermann & Bryan (1952) who

considered it an isolated language. Richardson (1957) groups it with Bantoid and Williamson (1971) treats

it as an isolated subgroup of her Bantu node. Clearly, the Tikar language has always been somewhat

problematic in terms of its classification. Dieu & Renaud (1983) placed it together with Ndemli, another

language that is hard to classify, although this may be simply an admission of ignorance. Piron (1996,

III:628) recognises it as part of her non-Bantu group and assigns it a co-ordinate branch with Dakoid,

Tivoid, Grassfields and the other branches of Bantoid (her ‘South Bantoid’) in opposition to Mambiloid.

Stanley (1991) notes that Tikar has many lexical similarities with the neighbouring Bafia (A53) but that the

morphosyntax is quite different.

Legendary Musician Quincy Jones traces his ancestry to Tikar people of Cameroon

The main sources for this language are Hagège (1969), Jackson & Stanley (1977), Jackson (1980, 1984,

1987, 1988), Stanley (1982a,b,c; 1991) and Stanley-Thorne (1995). Following the establishment of a

literacy programme, Tikar has been studied intensively and there are various academic papers on the syntax

as well as a doctoral thesis (Stanley 1991). Separately a series of lexical studies published in German exist

(Mamadou 1981, 1984). There is also an unpublished lexicon (Jackson 1988). The Bankim dialect,

Twumwu, is the principal one chosen for standardisation and development. Nonetheless, primary

comparisons do suggest that Tikar plays a role in the North Bantoid grouping and it is tentatively assigned a

co-ordinate position with the Dakoid-Mambiloid grouping.

African-American actress Alfre Woodard's traces her ancestry to Tikar people of Cameroon

History/Origin

According to historians, anthropologists, archeologists and oral tradition, the Tikar originated from north-eastern Cameroon, around the Adamawa and Lake Chad regions(present-day Adamawa, North and Far-North Provinces). Tikar migration southwards and westwards probably intensified with the raid for slaves by invading Fulani from Northern Nigeria in the 18th and 19th centuries. However, there is reason to believe that such migration was ongoing for centuries long before the invasion. The pressure of invasion by the Fulani raiders certainly occasioned the movements that led the Tikar to their current locations in the Western Grassfields (Bamenda Plateau) and Eastern Grassfields (Fumban) and the Tikar plain of Bankim (Upper Mbam) (Mbuagbaw, Brain & Palmer, 1987:26; Mbaku 2005:10-12). Upon arrival in the Grassfields, the Tikar found other populations in place, populations which had either migrated from elsewhere or had

inhabited the region for centuries. Their arrival occasioned population movements, just as did the arrival of others after them. Pre-colonial Cameroon, like the rest of Africa, was richly characterized by population movements not always induced by conflict or invasion.

Tikar elders

In the Bamenda Grassfields, those who claim Tikar origin include Nso, Kom, Bum,Bafut, Oku, Mbiame, Wiya, Tang, War, Mbot, Mbem, Fungom, Weh, Mmen, Bamunka, Babungo, Bamessi, Bamessing, Bambalang, Bamali, Bafanji, Baba (Papiakum), Bangola, Big Babanki, Babanki Tungo, Nkwen, Bambili and Bambui. Their alleged migration from the Upper Mbam River region was in waves, and mostly led by princes of Rifum fons, desirous of setting up their own dynasties (Nkwi & Warnier 1982:16; Nkwi1987:15-28). The authors of A History of Cameroon capture the Tikar migration asfollows:

“It was about three hundred years ago that increasing pressure from the north and

internal troubles plus the desire for new lands led to the splitting up of Tikar

groups into small bands, which, having left Kimi, drifted further west and southwest.

Some of these moved under the leadership of the sons of a Tikar ruler who

later called themselves Fons, the most common Bamenda term for paramount

chiefs. These groups, at various times reached what is now Mezam. Among the

earlier were those who came from Ndobo to the Ndop plain in the south of

Bamenda, where they formed small, politically independent villages a few

kilometers apart. No semblance of political unity was achieved. In the north-east

we have Mbaw, Mbem, and Nsungli, also settlements of Tikar, and below the

escarpment of a later date settlements of Wiya, Tang, and War. The main body of

this group however, set off under the leadership of their Fon and founded the

kingdom of Bum. The Bafut, Kom, and Nsaw were among the last to arrive.”

(Mbuagbaw et al. 1987:30).

Tikar Structures and Institutions

The political structures and institutions of the Tikar chiefdoms are very similar, and have influenced and been influenced by those of neighbouring non-Tikar groups. Some useful studies of Tikar political structures and institutions exist. Like other communities in the region, a Bamenda Grassfields Tikar community is led by a chief who is popularly known as fon, and whose chiefdomhenceforth we are going to call fondom. The Tikar in the Bamenda Grassfields mostlycame as small princely emigrant groups, to occupy areas that were already settled by other groups, with the result that in almost every Tikar fondom, are smaller fondoms that were either conquered or given protection by the Tikar, but that have largely retained their hereditary dynasties (Nkwi 1987:23-30; Mbuagbaw et al. 1987:30; Warnier 1985).

African-American lady Anita Woodley who traced her root to Tikar being welcomed with an emotional hug by a Tikar women. She was renamed Bekang.

It is in this way that during the 19th century fondoms such as Nso, Kom, Bafut, Bum and Ndu expanded their boundaries by incorporating or making tributaries of neighbouring fondoms, while at the same time entertaining relations of conflict and tension or conviviality with their fellow Tikar fondoms. Bum, for instance, though small, gained importance from its role as an “entrepot for the kola trade with Jukun and Hausa in the

north-west during the later part of the century”, and had “intermittent hostility” with Kom, its southern neighbours, while maintaining friendship with Nso and Ndu. Nso was mostly at conflict with Ndu and enjoyed an alliance with Kom, which was in competition with Bafut on its south-western boundary for the allegiance of much smaller fondoms (Mbuagbaw et al. 1987:31; Nkwi 1987:23-30; Yenshu 2001).

Blair Underwood in Tikar dress. Despite his DNA ancestry being of Igbo origin some part of it also has Tikar traces. He is captured his visiting Tikar Village of Babunga (Vengo) in Cameroon

“The Tikar Problem” in the Bamenda Grassfields

Today, the various groups of Tikar now settled in the Bamenda Grassfields reportedly trace their origin to Tibati, Banyo, Kimi and Ndobo of north-east Cameroon. Indeed, many royal lineages of various Grassfields fondoms claim to have originated from the“Ndobo-Tikar” country, a region that covers the area between the Upper Mbam and the Upper Noun. In certain cases in the Bamenda Grassfields – Bafut, Nkwen, Bambili and Bambui, their claims to being Tikar are not backed up by traceable direct contact, rituals, exchange or fon linking them with Rifum or Bankim, the most prestigious centres of the Upper Mbam valley. Culturally, the only institution of Tikar origin in the fondoms in question is the princes’ fraternity known as Ngirri, which the fondoms of Nso and Bamum for example, claim they acquired along with the paraphernalia from Rifum.

Other institutions such as Kwifon (ngwerong in Nso and its tributaries) are widespread in the Grassfields and correspond to those in the Tikar groups of the Upper Mbam region. In terms of languages spoken, it would appear that the Tikar of the Grassfields have through encounters and conviviality with other languages over the years, lost much of their linguistic similarities with the language of the Tikar who presently occupy the Tikar Plain. Some would argue that this makes of the Tikar of the Tikar plain the “true” Tikar.

The lack of any direct connections with Rifum notwithstanding, the fondoms in question could well be of Tikar origin, just asthey could well not be. Nkwi and Warnier have observed, for some fondoms to have

maintained oral tradition to origin even with little to authenticate those origin, thosefondoms must have an interest in doing so, and those traditions must be significant in their life (Nkwi & Warnier 1982:26; Nkwi 1987:23-28). This issue has been termed by scholars “The Tikar Problem”, and remains the subject of much ongoing debate (Chilver & Kaberry 1971; Fowler & Zietlyn 1996: 6-15; Yenshu 2001).

To Jean-Pierre Warnier, an anthropologist and archeologist who has worked extensivelyon pre-colonial Bamenda Grassfields, in many regards, the “Tikar Complex” is essentially an affair of the relations between fons on the one hand, and between a fon and his people on the other. First, for fons sharing common claims of origin, the Tikar Complex was a sufficient basis in principle to establish mutual obligations and taboos in

an assumed alliance without the need for recourse to ad hoc rituals. And for fons who did not share the same myths of origin, the mere reference to Ndobo-Tikar was reason enough to establish difference as legitimate basis for hostility or to render necessary a ritual of alliance, or in other instances to fuel sentiments of aristocratic superiority on the part of a “Tikar” fon. The prestige that came with declaring oneself as Tikar even when one was truly not was the fact of being seen as brother of renowned fondoms such as Nso

and Fumban. With the claim to being Tikar came a certain sense of entitlement or legitimacy to power over non-Tikar populations even when these were in the majority.

Beautiful Tikar tribe woman

Hence it must be stressed that Tikar traditions are first and foremost associated with royalty and royal lineages than with the wider group, and that acquiring either through payment or otherwise ‘authentic Tikar’ signs of legitimacy (e.g. regalia, Ngirri) directly from fons of Tikar descent was capable of bestowing some of that Tikarness on non-Tikar (Warnier 1985:264-266). Claims of Tikar origin mean less for most of the population than they do to their fons who seek political capital through such claims (Fowler & Zeitlyn 1996:6-15). This means that Tikar identity, like identities everywhere, is not only subject to renegotiation with new encounters, but that it cannot be understood divorced from the power dynamics that accord or deny value to identities.

African-American genealogist William Holland, dressed in traditional garb, shows off the ceremonial masks he bought on eBay. He plans to return the masks to the tribes from whence they came during a trip to Cameroon. He is from Oku clan of Tikar people

The same argument is developed in Elements for a History of the Western Grassfields, which Jean-Pierre Warnier co-authored with another anthropologist, Paul Nkwi, a Tikar from the fondom of Kom. “Claiming a Tikar origin was tantamount to claiming high status and legitimate political power”, and the closer to Bankim in rituals one was, the greater one’s legitimacy and power. Thus the Bamoun, Nso and others, by recognizing

the ritual ascendancy of the fon of Bankim and by maintaining a tradition where newparamount fons must be blessed at Rifum, a sacred lake near Bankim, earn themselves enough symbolic capital to pull their political and economic weight vis-à-vis their own subjects who may or may not claim Tikar origin, and especially in relation to otherfondoms and the agents of the state who are constantly shopping for local authorities as

vote banks and auxiliaries of the government. Similarly, the further and further away from Kimi one got, the more remote and difficult to substantiate their claims to be Tikar became (Nkwi & Warnier 1982:26-27)

Given that the Bamenda Grassfields were occupied long before alleged Tikar migration, the fact that the royal lineage claims Tikar descent does not imply that the fondom as a whole is Tikar, as the situation of Bum and Bafut would attest (Nyamnjoh 1985; Yenshu 2001). Among groups where Tikar origin is claimed by both royal and commoner lineages are Kom, Nso, Mbem and Weh (Nkwi & Warnier 1982:14-16).

However, given how common it was for people to move between groups in the 19th century for reasons of

trade, witchcraft, conflict, diplomacy and marriage inter alia, it is hardly surprising that few Tikar groups were pure and that fewer still are, even where commoners and royal lineages continue to claim Tikar origin. It was and still is commonplace for potential successors to compete for the throne on the death of a fon, and for the unsuccessful candidates to take refuge in other fondoms, taking along with them large numbers of supporters (Nkwi & Warnier 1982:24-28; Nkwi 1987:23-28). Here as elsewhere, the tendency to trace descent exclusively through the male line has often had the effect of oversimplifying the complexity of identities. Personally, I grew up in two palaces and belong with at least three fondoms, two Tikar (Bum and Mmen), a third Widikum (Mankon), and my biological and social origin can be traced to a lot more, such that

answering simple and often simplistic questions such as ‘where do you come from originally?’ is no simple feat (Nyamnjoh 2002). There is therefore no such thing as the essential, pure or homogenous Tikar community even amongst the so-called “true” Tikar of the Upper Mbam Tikar Plain, just as there is no essential African or American, as long as physical, cultural and ideological mobility are part and parcel of our reality and history. Being Tikar, being American or being anything for that matter, is always a negotiated reality subject to constant renegotiation in tune with new encounters, the aspirations of the moment and the relationships that engender such aspirations and make possible or impossible their realization (Nyamnjoh 2002, 2005, 2007a&b).

Tikar people

Trading and Relations with Others

Prior to the 19th century the Grassfields were a largely isolated region. Given the high altitude, mountainous and difficult landscape of the Grassfields, the lack of navigable waterways, and the fact that transportation prior to the opening of motorable roads was largely done by human porterage, the region did not benefit from the vast trading networks that crossed Africa in various directions, and which coastal chiefdoms took

great advantage of. The mountain range that extends from the Grassfields to Lake Chadand the Jos Plateau of Nigeria remained largely undisturbed until the 19th century (Nkwi & Warnier 1982:78). Trade was mainly in slaves (see Chem-Langhëë 1995, for more on 19th and 20th century slavery in the Grassfields), ivory, kola nuts, salt, oil, iron, cloth pearls and cowries, which in certain regions were adopted as forms of payment. During the 19th century the Bamenda Grassfields was still very largely outside the trading networks of the Benue and Adamawa. But these two networks would spread themselves into the Bamenda Plateau at the end of the 19th Century, thereby offering the communities of the region the possibility for differentiation (Rowlands 1978; Warnier 1985:141-148).

Tikar wedded couples in their traditional wedding dress in Washington DC

Two Tikar fondoms, Bum and Fumban, occupied strategic positions as trade routes, Bum for trade with Wukari and Fumban for trade with Banyo. At first, trade between the Benue and the Grassfields was still mainly in the hands of the local population, which was not the case with trade with the Adamawa region, which was totally under the control of the Hausas, whose impact in the Grassfields has been such that there is hardlya local market today where one does not find a Hausa trader on a mat with items such as herbs, salt, powder and little packets of mixtures of cooking ingredients of all sorts. The mountainous nature of the region added to many rivers to make it difficult to travel, especially at the rainy season, meaning that only certain routes were possible for traders. Kola nut mostly produced in Nsungli and Nso was sold in Nigeria through Banyo, Yolaand Takum, and the importance of the Banyo route was only diminished when the French and British set up customs posts. The donkeys seen today in Nso (where they are called “the kola animals”) and elsewhere in the Grassfields were probably introduced during the kola trade (Warnier 1985:141-148). In the second half of the 19th century, the fon of Bafut was allegedly so powerful that he used to send traders as far away as Takum (Warnier 1985:267). The Western and Eastern Grassfields along with their Tikar fondoms have yielded some of the most enterprising entrepreneurs in present day Cameroon

(Warnier 1993).

Procession of Tikar elders

Culture

The Tikar have elements of matrilineal and patrilineal descent. Their folk belief states that during pregnancy the blood that the woman would normally release during menstruation forms parts of the fetus. This blood is said to form the skin, blood, flesh and most of the organs. The bones, brain, heart and teeth are believed to be formed from the father's sperm. In the case of a son the masculinity also comes from this. The Tikar are also noted as mask-makers.

The primary religion of the Tikar people is Islam

Dance mask, Tikar, Cameroon

wood, rattan, trade cloth, paint - 49cm

gift of Peter Natan

wood, rattan, trade cloth, paint - 49cm

gift of Peter Natan

The History of the Masks of the Tikar

The Tikar people have focused on education for generations. Teachers taught boys vocational skills which included craft-making, woodcarving, mask carving and making bronze sculptures. They developed a process of using hot wax and bronze to create masks and statues to be used during agricultural ceremonies and festivals.

Tikar facial mask

The Tikar or Twumwu people currently number between 44,000 and 250,000 (depending on the source) in Cameroon, in the grasslands areas of central Africa. More than 25 peoples of this area currently claim Tikar origin including the Nso, Kom, Bum and more. While they speak a variety of languages (even though French and English are their official languages), they all claim to have similar ancestors linking their history and culture. Approximately 65 percent of the population is Islam with another 20 percent claiming Christianity. A largely agricultural people, their main crops are cocoa, coffee, bananas, plantains, sugar cane and cassava, among many others.

Tikar Buffalo mask

Ceremonies

Many believe the Tikar masks are originally used to celebrate agricultural ceremonies or festivals with a plentiful harvest resulting in even larger, more elaborate celebrations. Hosting an honored guest was also cause for celebration as these extremely political people were wise to treat foreign dignitaries with respect. During these festival,s plam wine, billet beer and carbonated drinks are served along with a chicken, goat, steer or sheep.

Alfie Woodard has Tikar tribe DNA

Tikar Batibo fondom

Condolezza Rice has Tikar tribe DNA

Tikar Bambui fondom

Very nice pictures...keep it up...

ReplyDeleteBafut population alone is more than 100,000 far more than the 47,000 for the entire Tikaris on this page. Please updated statistics very important.

ReplyDeleteEnjoyed the history and beautiful pictures. My dna shows Cameroon, Benin, Togo and Nigeria and more in Africa. Very nice post thank you for sharing.

ReplyDeleteKom is not mentioned here, Kom is also tribes came from Tikari and the population of Kom alone is about 180 000 in habitant. Check statistic,Plz

ReplyDeleteJadwal Bola Terupdate Liputan6

ReplyDeleteBerita Bola Terkini Liputan6

Jadwal Liga Inggris Liputan6

Klasemen Liga Inggris Liputan6

Klasemen Liga Spanyol Liputan6

Jadwal Liga Spanyol Liputan6

Berita Terkini Timnas Indonesia Liputan6

Berita ISL 2015 Liputan6

Persib Bandung Hari Ini Liputan6

Arema Cronus Hari Ini Liputan6

Persipura Hari Ini Liputan6

Real Madrid Hari Ini Liputan6

Juventus Hari Ini Liputan6

Inter Milan Hari Ini Liputan6

AC Milan Hari Ini Liputan6

Manchester United Hari Ini Liputan6

Berita Arsenal Liputan6

Berita Liverpool Liputan6

Jadwal QNB Leagua 2015 Liputan6

Berita Bola Terkini Jumat 17 April 2015 Liputan6