NDEBELE (MATEBELE) PEOPLE: THE WARRIOR NGUNI PEOPLE OF ZIMBABWE

"The chameleon gets behind the fly, remains motionless for some time, then he advances very slowly and gently, first putting forward one leg and then another. At last, when well within reach, he darts his tongue and the fly disappears. England is the chameleon and I am that fly." —Lobengula,the second and last king of Ndebele.

Ndebele traditional dancers performing their tribal Isitshikitsha dance.Bulawayo, Zimbabwe

The northern Ndebele (Northern Ndebele: amaNdebele) /Matebele are a Bantu-speaking nguni people of southwestern Zimbabwe (formerly Matebeleland) who now live primarily around the city of Bulawayo and form 20% of the population of Zimbabwe. By the time of colonial rule, the Ndebele state had existed as a centralised political reality in the south-western part of theZimbabwean plateau with people who were conscious of being Ndebele and who spoke IsiNdebele as their national language (Cobbing 1976; Ndlovu-Gatsheni 2004). The Ndebele existed as an independent nation up to 1893 when King Lobengula was violently removed from power by the British colonialists. They were formerly an offshoot of nguni nation of Natal in Southern Africa, who share a common Ndebele culture and Ndebele language. Their history began when a Zulu chiefdom split from King Shaka in the early 19th century under the leadership of Mzilikazi, a former chief in his kingdom and ally. Under his command the disgruntled Zulus went on to conquer and rule the chiefdoms of the Southern Ndebele. This was where the name and identity of the eventual kingdom was adopted. Mzilikazi originally called his land Mthwakazi and the whites called it Matebeleand.

During a turbulent period in Nguni and Sesotho-Tswana history known as the Mfecane, Mzilikazi regiment, initially numbering 500 soldiers, moved west towards the present-day city of Pretoria, where they founded a settlement called Mhlahlandlela. They then moved northwards in 1838 into present-day Zimbabwe where they overwhelmed the Rozvi, eventually carving out a home now called Matabeleland and encompassing the west and south-west region of the country. In the course of the migration, large numbers of conquered local clans and individuals were absorbed into the Ndebele nation, adopting the Ndebele language and culture. Historically the assimilated people came from the Southern Ndebele, Swazi, Sotho-Tswana, and amaLozwi/Rozvi ethnic groups.

On the streets of the Zimbabwean city of Bulawayo, a group of men and women commemorate the life of King Mzilikazi, the founder of the Ndebele kingdom, in this shot by Clayton Moyo, who says the annual event is dominated by song and dance.

Today, the (ama)Ndebele of Zimbabwe or bakwaKhumalo (the people of Khumalo) are the second largest population of the country and their language known as isiNdebele, and just like their South African (ama) Ndebele counterpart is one of the official languages of the state.

language

The Northern Ndebele language, isiNdebele, Sindebele, or Ndebele is an African language belonging to the Nguni group of Bantu languages, and spoken by the Ndebele or Matabele people of Zimbabwe.

isiNdebele is related to the Zulu language spoken in South Africa. This is because the Ndebele people of Zimbabwe descend from followers of the Zulu leader Mzilikazi, who left KwaZulu in the early nineteenth century during the Mfecane.

The Northern and Southern Ndebele languages are not variants of the same language; though they both fall in the Nguni group of Bantu languages, Northern Ndebele is essentially a dialect of Zulu, and the older Southern Ndebele language falls within a different subgroup. The shared name is due to contact between Mzilikazi's people and the original Ndebele, through whose territory they crossed during the Mfecane.

Matebeleland,Zimbabwe

Linguistically, the (ama)Ndebele of South Africa, particularly the Southern (ama)Ndebele, differ radically from their Zimbabwean counterparts. Scholars such as Van Warmelo (1930:7), for instance, state clearly the language of the (ama)Ndebele of South Africa differs from that of Mzilikazi's followers.

IsiNdebele of the (ama)Ndebele of South Africa is more influenced by Sepedi because of their close contact for many years, while that of the (ama)Ndebele of Zimbabwe is closer to isiZulu, most probably because they never stayed for long in close contact with the Sotho speaking tribes when they were on their way northwards. The following few lexical examples illustrate differences between the two languages.

IsiNdebele of South Africa IsiNdebele of Zimbabwe English

ihloko Ikhanda ‘head’

ipumulo ikhala ‘nose’

umkghadi ixaba ‘skin blanket’

isiphila ummbila ‘maize’

umsana umfana ‘boy’

umntazana intombazane ‘girl’

ukuluma inxwala ‘first fruit ceremony’

isokana ijaha ‘young man’.

Ndebele man and his wife

Origin

Most Ndebele trace their ancestry to the area that is now called KwaZulu-Natal. The history of the Ndebele people can be traced back to Mafana, their first identifiable chief. Mafana’s son and successor, Mhlanga, had a son named Musi who, in the early 1600’s, decided to move away from his family (later to become the mighty Zulu nation) and to settle in the hills of Gauteng near Pretoria.

Ndebele people of Zimbabwe

After Chief Musi’s death, his eldest son, Manala was named future chief. This was challenged by another senior son, Ndzundza and the group was divided by the resulting squabble between the two. Ndundza was defeated and put to flight. He and his followers headed eastwards, settling in the upper part of the Steelport River basin at a place called KwaSimkhulu, near present-day Belfast, leaving Manala to be made chief of his father’s domain. Two further factions, led by other sons, then broke away from the Ndebele core. The Kekana moved northwards and settled in the region of present-day Zebediela, and the other section, under Dlomo, returned to the east coast from where the Ndebele had originally come.

By the middle of the 19th century, the Kekana had further divided into smaller splinter groups, which spread out across the hills, valleys and plains surrounding present-day Mokopane (Potgietersrus), Zebediela and Polokwane (Pietersburg). These groups were progressively absorbed into the numerically superior and more dominant surrounding Sotho groups, undergoing considerable cultural and social change. By contrast, the descendants of Manala and Ndzundza maintained a more recognisably distinctive cultural identity, and retained a language which was closer to the Nguni spoken by their coastal forebears (and to present-day isiZulu). Hence, the formation of the Southern vs. Northern Ndebele.

Life was simple for the Khumalos until the rise of chief Zwide and his tribe Ndwandwe. The Khumalos had the best land in Zululand, the Mkhuze: plenty of water, fertile soil and grazing ground. But in the early 19th century, they would have to choose a side between the Zulu and the Zwide. They delayed this for as long as they could. To please the Ndwandwe tribe, the Khumalo chief Mashobane married the daughter of the Ndwandwe chief Zwide and sired a son, Mzilikazi. The Ndwandwes were closely related to the Zulus and spoke the same language Nguni using different dialects.

When Mashobane did not tell Zwide about patrolling Mthethwa amabutho (soldiers), Zwide had Matshobana killed. Thus his son, Mzilikazi, became leader of the Khumalo. Mzilikazi immediately mistrusted his grandfather, Zwide, and took 50 warriors to join Shaka. Shaka was overjoyed because the Khumalos would be useful spies on Zwide and the Ndwandwes. After a few battles, Shaka gave Mzilikazi the extraordinary honour of being chief of the Khumalos and to remain semi-independent from the Zulu, if Zwide could be defeated.

This caused immense jealousy among Shaka's older allies, but as warriors none realised their equal in Mzilikazi. All intelligence for the defeat of Zwide was collected by Mzilikazi. Hence, when Zwide was defeated, Shaka rightly acknowledged he could not have done it without Mzilikazi and presented him with an ivory axe. There were only two such axes; one for Shaka and one for Mzilikazi. Shaka himself placed the plumes on Mzilikazi's head after Zwide was vanquished.

The Khumalos returned to peace in their ancestral homeland. This peace lasted until Shaka asked Mzilikazi to punish a tribe to the north of the Khumalo, belonging to one Raninsi a Sotho. After the defeat of Raninsi, Mzilikazi refused to hand over the cattle to Shaka. Shaka, loving Mzilikazi, did nothing about it. But his generals, long disliking Mzilikazi, pressed for action, and thus a first force was sent to teach Mzilikazi a lesson. The force was soundly beaten by Mzilikazi's 500 warriors, compared to the Zulus' 3,000 warriors (though Mzilikazi had the cover of the mountains). This made Mzilikazi the only warrior to have ever defeated Shaka in battle.

Shaka reluctantly sent his veteran division, the Ufasimbi, to put an end to Mzilikazi and the embarrassing situation. Mzilikazi was left with only 300 warriors who were grossly out-numbered. He was also betrayed by his brother, Zeni, who had wanted Mzilikazi's position for himself. Thus Mzilikazi was defeated. He gathered his people with their possessions and fled north to the hinterland to escape Shaka's reach. After a temporary home was found near modern Pretoria, the Ndebele were defeated by the Boers and compelled to move away to the north of the Limpopo river.

Ndebele people in their domestic set-up in Matebeleland. Circa 1930

The Founding of the Kingdom. of Ndebele

The Matabele saga began in 1822, when Mzilikazi (meaning "path of blood) of the Kumalo, a Ndwandwe clanwhich had been incorporated into Shaka's new Zulu kingdom, was sent to attack the Swazis. Mzilikazi succeeded in capturing a large number of Swazi cattle, but rashly decided to keep some of them instead of sending them all to Shaka. Aware that the Zulu king was not likely to look kindly on this sort of thing, he went into hiding in the hills of the Kumalo country. Eventually the Zulus found him, took him by surprise and scattered his followers, but Mzilikazi and a few hundred others escaped across the Drakensberg Mountains and onto the High Veldt of what was to become the Transvaal. Here they encountered scattered groups of Sotho, Tswana and other peoples, many of whom had already been impoverished by Nguni or Afrikaner encroachment, and whose traditional fighting methods were no match for the Zulu-style tactics introduced by the newcomers.

There Mzilikazi's people continued to pursue their new vocation of cattle rustling. They soon made themselves rich at the expense of the local Sotho and Tswana tribes, many of whose survivors were incorporated more or less willingly into their ranks in the same way as the Zulus had done to the Ndwandwe. This was the beginning of the class system which characterised their society in the second half of the century. The "amaZansi" or "those from the south", in other words the original Ndwandwe families, constituted the

aristocracy. Below them came the "abeNhla" or "those from the road", who were absorbed during their time on the High Veldt. Later, when they moved north of the Limpopo River, the local Shona and Kalanga tribes were brought in under the name of "Holi". It was about this time that the name Matabele (or Ndebele) first came into use. Among the various theories about its origin, the most appealing is that it meant something like "They Disappear From Sight", referring to the way in which the warriors took cover behind their great Zulu-style shields.

Ndebele village in Matebeleland.Circa 1890

Mzilikazi seems to have been popular with his subjects, and he ruled successfully until his death in 1868, in contrast to the fate of his contemporary Shaka. White missionaries, impatient at his refusal to let his people go to work for them, often portrayed him as a savage tyrant who ruled solely by terror, but others - like the Scottish missionary Robert Moffat, got on well with him and regarded him as intelligent and statesmanlike. Matabele tradition suggests that he was genuinely mourned as the "founder of the nation". Of course nineteenth century African ideas of government will not always appeal to modern tastes, and people were executed for witchcraft, impaled, mutilated or fed to crocodiles. And ruthless aggression against neighbouring peoples weak enough to be exploited was par for the course. Even Moffat admitted that Mzilikazi was responsible for "the desolation of many of the towns around us - the sweeping away the cattle and valuables - the butchering of the inhabitants". One of his native informants recalled "the great chief of multitudes... the chief of the blue-coloured cattle", who was so confident of his strength that he had refused to flee when the invaders approached, heralded by “the smoke of burning towns”. "The onset was as the voice of lightning, and their spears as the shaking of a forest in the autumn storm. The Matabele lions raised the shout of death,

and flew upon their victims… Their hissing and hollow groans told their progress among the dead… Stooping to the ground on which we stood, he took up a little dust in his hand; blowing it off, and holding out his naked palm, he added, 'That is all that remains of the great chief of the blue-coloured cattle!'" Something of this reputation remains to this day in southern Africa, where the fearsome army ants, famous for their aggressive wars against the local termites, are still known as "Matabele ants."

But the Matabele were not always the aggressors. The Griquas and Koranas from the south had horses and guns, and were said to be the worst cattle thieves in southern Africa (quite an achievement!) In 1831 they descended on the Matabele settlements and drove off a huge herd. They might have been surprised to encounter no resistance, but after three days riding they decided that they had got away with it. After all, the Matabele were entirely on foot and could hardly have followed them undetected across the open veldt. So on the third night the thieves had a feast and went to sleep. During the night a Matabele “impi” - which had indeed kept up with them by marching at night - surrounded them at a place now known as Moordkop, or Murder Hill. Mzilikazi got his cows back, and only three Griquas escaped with their lives.

In 1832 a Zulu "impi" or army attacked Mzilikazi's headquarters while his warriors were away on a raid. The subsequent battle was a draw, but the Matabele suffered serious losses. Knowing that the Zulus were the one people he could not intimidate, the king decided to take his people out of their reach once. First he moved them a hundred miles to the west into the Marico Valley, but in 1836 the vanguard of the Boers "Vortrekkers" began to arrive there. Like his contemporary the Zulu king Dingaan, Mzilikazi decided to

strike first, but also like Dingaan he failed to finish the job. At first the Boers were taken by surprise and several of their camps were wiped out, but most of the men escaped. A Matabele "impi" of around 3,000 men attacked the now concentrated Boers at the Battle of Vegkop, but were unable to storm their wagon laager and were driven off with heavy losses. Then the Zulus and Griquas returned to the attack, and Mzilikazi realised that he could not hope to survive on the High Veldt against such a combination of enemies.

Ndebele girls of Matebeleland (Zimbabwe). Circa 1890

He led his people north once again, this time across the Limpopo River into the country which became known as Matabeleland, in the west of modern Zimbabwe. Mzilikazi called his new nation Mthwakazi, a Zulu word which means something which became big at conception, in Zulu "into ethe ithwasa yabankulu" but the territory was called Matabeleland by Europeans. This was a well watered country with plenty of grazing, and had the further advantage that it was easily defensible. To the north an almost impassable forest stretched away to the Zambezi, while the south and west were protected by the rugged Matopo Hills. The main road from the south entered the country via the precipitous Mangwe Pass, which was easily defended by a regiment stationed at a nearby kraal. The only vulnerable frontier was on the east, where it bordered on the territory of the local Shona tribes. In 1852, the Boer government in Transvaal made a treaty with Mzilikazi. However, gold was discovered in Mashonaland in 1867 and the European powers became increasingly interested in the region. But Mzilikazi defeated the Shona, reduced them to vassalage, and enjoyed a period of relative peace until his death in 1868 (though his last fight with the Boers was as late as 1847, when he sent an "impi" back south across the Limpopo in search of more cattle). Nzilikazi was a statesman of considerable stature, able to weld the many conquered tribes into a strong, centralised kingdom.

Lobengula and the Defeat of the Matabele.

Mzilikazi's favourite son Lobengula succeeded to the throne in 1870, after a brief civil war, and soon resumed his father's career of conquest. His armies campaigned in all directions, consolidating his power over the neighbouring tribes and in some areas even extending it. Among their opponents and victims in this period were the Tswana in the west, and the Barotse, Tonga and Ila beyond the Zambezi. In about 1887 the Tonga, fed up with the depredations of local Chikunda slave raiders, rashly invited Lobengula to

come and help sort them out. An "impi" duly arrived and wiped out the slavers, but the Tonga had not taken the precaution of hiding their cattle, and of course the Matabele found the temptation irresistible. They went home with all the beasts they could round up in payment for their services, then over the next few years came back twice more for the rest of what they described as "our cattle which we have left among the Tonga", inflicting immense damage in the process.

But Lobengula was careful to avoid trouble with white men, and he encouraged hunters and traders (including the famous elephant hunter F. C. Selous) to visit his country. A British Resident named Captain Patterson was sent to Bulawayo in 1878. Patterson was an arrogant character who insisted on travelling wherever he liked against the king's orders; one day he and his whole party disappeared, and it was rumoured that Lobengula had had them murdered, but nothing was ever proved, and the British, preoccupied by then with events in Zululand, took no action. Lobengula raised no objection when in 1885

Britain established a Protectorate over Bechuanaland to the west (now Botswana), which had once been a favourite Matabele raiding ground. This conciliatory attitude, as well as the remoteness of the country, enabled the Matabele to retain their independence long after the defeat of their Zulu cousins in the south. But by the late 1880s the impetus of the European "Scramble for Africa" was unstoppable.

In October 1888 Cecil Rhodes sent agents of his British South Africa Company to trick Lobengula into signing away the mineral rights in his kingdom. The king soon saw through this con trick, but was persuaded to allow prospectors to enter the country anyway. Then in May 1890 Rhodes revealed his true intentions, dispatching a heavily armed "Pioneer Column" from Bechuanaland, consisting of about two hundred civilians with an escort of four hundred British South Africa Company and Bechuanaland Police. Avoiding a direct confrontation with Lobengula, the invaders skirted around Matabeleland proper and marched into Shona territory further north, where they built a fortified post at Fort Salisbury.

Lobengula protested, but held back from giving his "impis" the order to attack. In doing so he missed what may have been his only chance to keep his kingdom. Soon the white colonists were building more forts, establishing farms and mines, and luring young Shona and Matabele men to desert Lobengula and work for them. In 1891 Mashonaland became a British Protectorate, situated at the very point where the borders of Matabeleland were most exposed to attack. Many of the Shona welcomed the whites as protectors against

their Matabele masters, and took the opportunity to thumb their noses at them from the imagined security of the new settlements. But the king was not prepared to put up with disrespect from his own "dogs", as he called the Shona. In June 1893 a rebel chief stole some Matabele cattle, an "impi" was sent across the border in pursuit. The warriors had instructions not to molest the whites, but they slaughtered many of their Shona employees, burnt their kraals and took all the cattle they could find. One white settler at Fort Victoria recalled how "insolent Matabele swaggered through the streets of the town with their bloody spears and rattling shields". Just like the Matabele, the subjects of Queen Victoria were not prepared to put up with this sort of insult from what they saw as "lesser breeds". Soon the colonists were advancing into Matabeleland in force from two directions.

1835 waterpainting of Ndebele (Matabele) warriors by Charles bell

The Ndebele People, Culture and Language

The southern column was mainly a diversion, and played a minor part in the fighting. The main threat came from the north-east, where two more columns, from Forts Salisbury and Victoria, rendezvoused at Iron Mine Hill and marched on Lobengula's kraal at Bulawayo. Together they numbered six hundred and ninety mounted white men with Martini Henry rifles, about four hundred Shona tribesmen on foot, two seven-pounder field guns, and eight machine guns, of which five were Maxims. There was also a steam-powered

searchlight for protection against night attacks. The transport wagons were designed to be formed in Boer style into a defensive laager. To face this powerful force, Lobengula had about 12,500 warriors altogether, not counting a large force which he had sent off to the Zambezi before the crisis erupted. On 25th October 1893, at Bonko on the Shangani River, 3,500 Matabele attacked the two laagers of the north-eastern column in the early hours of the morning. Despite the demoralising effects of the searchlight and the

unexpected rapid fire from the Maxims, the warriors attacked with great determination, but they were beaten off without ever reaching the wagons, with the loss of about five hundred men.

Lobengula forbade any more attacks to be made on laagered wagons, but instead ordered his "impis" to wait until the marching columns were crossing the only useable ford across the Umguza River on their way to Bulawayo. Then they should attack while the wagons were half way across, so that the whites would have no time to form them into a laager. (Is it coincidence that the Zulus had beaten the British in similar circumstances at Intombe Drift in 1879, when a column had been split by a flooded river and defeated in

detail? It is interesting to speculate that some of the "indunas" with Zulu names in Lobengula's army might have been advisors employed to pass on the lessons of the Anglo-Zulu War.)

But unfortunately for Lobengula, his orders were disobeyed. Just before noon on 1st November the eastern column stopped for lunch on top of a low hill in open country not far from the Bembesi River. The colonists seem to have thought that they were safe as long as they stayed away from the dense bush which lay a few hundred yards away, and although they formed two wagon laagers, one on either side of a small deserted kraal, they rashly sent their livestock to graze on lower ground about a mile away. Some of the men put their rifles aside and began to mend their torn clothes. But what they did not know was that 6,000 Matabele were marching parallel to them under the cover of the bush. The "impi" included two elite regiments, "Ingubo" and "Imbizo", and was well supplied with guns, including many modern breech-loading rifles. Perhaps the "indunas" in command felt that as their force was overwhelmingly superior, they were justified in disobeying orders and launching an immediate attack while the whites were vulnerable. Suddenly the young Zansi warriors of "Ingubo" and "Imbizo" burst out of cover and charged the nearest laager, five hundred yards away across open ground. They fired their guns on the move, but their shooting was inaccurate and caused few casualties, while the startled colonists raced to get their Maxims into action. This may have been the first time in history that regular soldiers charged against massed machine guns, in the open and in broad daylight. The outcome may have surprised the Matabele, but to us, with hindsight,it was inevitable. A survivor from "Imbizo" recalled that when the "sigwagwa", as they called the Maxims, opened fire "they killed such a lot of us that we were taken by surprise. The wounded and the dead lay in heaps." Nevertheless the warriors rallied and returned to the charge at least three times, advancing to within a hundred and ten yards of the laager. Sir John Willoughby, who was with the column, later said that "I cannot speak too highly of the pluck of these two regiments. I believe that no civilised army could have withstood the terrific fire they did for at most half as long." But the only result of their incredible courage and discipline was the loss of more than half their number before they finally retired.

What was worse, the rest of the Matabele army failed to support them, but fell back and allowed the column to cross the Bembesi and Umguza Rivers unopposed. Lobengula fled northwards, trying to find refuge among the Ngoni across the Zambezi, but either died on the way, probably from smallpox. Only one more battle remained to be fought - the "last stand" of the Shangani Patrol, so stirringly related recently in these pages by W. P. Bollands. But this was actually a mistake, as by now both sides were seeking to end the

war. The British South Africa Company appropriated most of the best land for sale to white farmers, and confiscated most of the Matabele cattle. In 1896 the people launched a desperate rebellion in which twice as many whites were killed as in 1893. This time the Matabele abandoned their traditional tactics, and fought mainly as skirmishers with rifles. Some of them had been employed by the British as policemen, and had obviously learned to shoot. As Summers and Pagden remark in their book, observing that the whites suffered eleven percent battle casualties in this campaign, twice the rate of the 1893 war, "the Matabele had become a fair marksman".

But numbers eventually told against them, and after six months of fighting they were beaten, more by starvation than by military force.

Zimbabwe War of Liberation

During the Zimbabwean War of Liberation, the main liberation party, Zimbabwe African People's Union (ZAPU), split into two groups in 1963, the split-away group renamed itself the Zimbabwe African National Union (ZANU). Though these groups had a common origin they gradually grew apart, with the split away group, ZANU, recruiting mainly from the Shona regions, while ZAPU recruited mainly from Ndebele-speaking regions.

ZIPRA was the anti-government force based around the Ndebele ethnicity, led by Joshua Nkomo, and the ZAPU political organization. Nkomo's ZIPRA trained and planned their missions in Zambian bases. However, this was not always with full Zambian government support: by 1979, the combined forces based in Zambia of ZIPRA, Umkhonto we Sizwe (the armed wing of the African National Congress of South Africa) and South-West African SWAPO fighters were a major threat to Zambia's internal security. Because ZAPU's political strategy relied more heavily on negotiations than armed force, ZIPRA did not grow as quickly or elaborately as ZANLA, but by 1979 it had an estimated 20,000 combatants, almost all based in camps around Lusaka, Zambia.

1980's Matabeleland Genocide (Ethnic Cleansing)/ Gukurahundi

The Gukurahundi (Shona: "the early rain which washes away the chaff before the spring rains") refers to the suppression by Zimbabwe's 5th Brigade in the predominantly Ndebele speaking region of Matabeleland, who most of whom were supporters of Joshua Nkomo and ZAPU.

Joshua Nkomo,an Ndebele man,signing an accord with Robert Mogabe

Robert Mugabe, then Prime Minister, had signed an agreement with North Korean President Kim Il Sung in October 1980 to have the North Korean military train a brigade for the Zimbabwean army. This was soon after Mugabe had announced the need for a militia to "combat malcontents." Mugabe replied by saying Matabeleland dissidents should "watch out," announcing the brigade would be called "Gukurahundi." This brigade was named the Fifth Brigade. The members of the Fifth Brigade were drawn from 3500 ex-ZANLA troops at Tongogara Assembly Point, named after Josiah Tongogara, the ZANLA general. The training of 5 Brigade lasted until September 1982, when Minister Sekeramayi announced training was complete.

The first Commander of the Fifth Brigade was Colonel Perence Shiri. The Fifth Brigade was different from all other Zimbabwean army units in that it was directly subordinated to the Prime Minister office, and not integrated to the normal army command structures. Their codes, uniforms, radios and equipment were not compatible with other army units. Their most distinguishing feature in the field was their red berets.

The 5th Brigade conducted public executions in Matabeleland, victims were often forced to dig their own graves in front of family and fellow villagers. The largest number of dead in a single killing was on 5 March 1983, when 62 young men and women were shot on the banks of the Cewale River, Lupane.Seven survived with gunshot wounds, the other 55 died. Another way 5 Brigade used to kill large groups of people was to burn them alive in huts. They did this in Tsholotsho and also in Lupane. They would routinely round up dozens, or even hundreds, of civilians and march them at gun point to a central place, like a school or bore-hole. There they would be forced to sing Shona songs praising ZANU, at the same time being beaten with sticks. These gatherings usually ended with public executions. Those killed were innocent civilians, ex-ZIPRA freedom fighters, ZAPU officials, or anybody chosen at random.

Economy

The precolonial Ndebele were a cattle-centred society, but they also kept goats. The most important crops, even today, are maize, sorghum, pumpkins, and at least three types of domesticated green vegetables ( umroho ).

Ndebele people lives in Matebeleland where Victorial Falls is located in Zimbabwe

Since farm-laborer days, crops such as beans and potatoes have been grown and the tractor has substituted for the cattle-drawn plow, although the latter is still commonly used. Pumpkins and other vegetables are planted around the house and tilled with hoes. Cattle (now in limited numbers), goats, pigs, and chickens (the most prevalent) are still common.

Industrial Arts. Present crafts include weaving of sleeping mats, sieves, and grain mats; woodcarving of spoons and wooden pieces used in necklaces; and the manufacturing of a variety of brass anklets and neck rings.

Balancing Rock,Bulawayo

The ndebele people of Zimbabwe are also very known for their colourful beads making.

Ndebele beads

The Ndebele Beadwork

Beadwork is a hundren and fifty year old art among the Ndebele, and plays an important role in tribal custom, but it is an art that is dying.

The encroachement of western civilization has eroded the Ndebele's tribal way of life, and the gradual disappearance of a true tribal existence will mean the inevitable dwindling of many of its age old rituals, customs and art forms.

To the Ndebele however, beadwork is more than just an art form. It is an essential part of their cultural and ethnic identity, and serves several functions in tribal society. Beads are used to adorn the body and decorate cereminial objects and items of clothing. Among the Ndebele, beadwork is worn almost exclusively by the women, for whom the different beadwork and beaded garments serve as an identification os status from childhood.

Beadwork is an integral part of all Ndebele rituals and ceremonies, which mark importantevents in family life, from the birth of a child, to initiation into adulthood, to marriage, to burial.

A bride may work for 2-3 years on a piece of beadwork to present to her future in-law family, and the more intricate and impressive the piece, the more she will be favored by her husband's family and respected by the community.

Likewise, a woman may spend many months or even years on intricate beadwork to adorn funeral garments. The Ndebele have a strong belief in the afterlife, so a great deal of care goes into the munufacture of burial garments.

The amount of skill patience and craftmanship required to make a Ndebele beaded garment is hard to imagine. Some Ndebele beaded garment are made with over 300,000 individually strung beads, and the careful artis passed mother to daughter.

The Ndebele beads have always been imported and are identical to those used by north American Indians. In earlier times, the Ndebele beadwork was mianly white, with just a few colored beads sewn onto the background. Newer pieces (from the 1960's onwards) make use of many more colored beads.

Older pieces of beadwork were sewn onto leather and newer pieces have made use of canvas. Yet anothe rdevelopment has been the introduction of plastic sheeting being used as a backing for the beadwork and the useof colored tape inplace of the beads. Hte availability of colored plastic materials over the last few decades has heralded an evolution in the art of the Ndebele adornment, and is an interesting example of how tribal culture has used the products of Western civilization to its advantage. Another interesting example of the mix of Western and African cultures is the recent incorporation of Western symbols of status into the beadwork of the Ndebele. Looking closely at some of the contemporary Ndebele beadwork you will find electric light fittings, telephone poles and even jet airplanes.

Each piece of beadwork is a work of art in itself. A fully outfitted woman may be wearing as many as half a million beads. The beadwork of the Ndebele is arguably the most impressive in the world, thanks not only to its sheer volume of beads, but also to its magnificently intricate designs and vibrant use of color. The beads are the history books and the story tellers of the Ndebele. The evolution of beadwork over the decades tells a story, in pictures and symbols, of a tribe that refused to die.

The Social structure of the Ndebele Tribe

The way in which Mzilikazi built his Ndebele Kingdom as a result of the need for it to grow in numbers beyond the just the mere 300 people, that he left with when he was fleeing from Tshaka, through raids and assimilation of youths and women. In order to be able maintain the culture and beliefs of his people, Mzilikazi stratified his kingdom into three distinct groups or classes with separate societal privileges.

Ndebele drummers of Matebeleland,Zimbabwe

The Ndebele state was divided into three groups, the Zansi, Enhla and Hole. The Zansi were the original followers of Mzilikazi from Zululand. They were fewer in number, but they formed a powerful portion of the society. They were the upper class of the Ndebele society, the aristocrats. The Zansi were divided amongst themselves into clans according to their totems and clan leaders formed the political elite of the Kingdom.

Below the Zansi were the Enhla. These were people who had been conquered and incorporated into the Ndebele state before it came into Zimbabwe. They comprised mainly people of Sotho, Venda and Tswana origin and they were more numerous than the Zansi.

Ndebele woman,Zimbabwe

The Hole formed the lowest but largest class in the kingdom. They were a fusion of Nguni, Sotho, Tswana and Shona. There were two types of Hole. The first group comprised chiefdoms that were moved or voluntarily migrated into Ndebele settlement. Examples of such people include the Nanzwa from Hwange, Nyai from Matobo, Venda from the Gwanda-Beit Bridge area, and the Shona from western Mashonaland. Most of these chiefdoms, unable to resist their enemies, chose to go and live under the security of the Mzilikazi. The youths of these chiefdoms were merged to form the Impande and Amabukuthwani military regiments, while the elders were given land to settle under one of their chiefs.

Some of these elders were even privileged into positions of being the king’s intelligence agents, thereby forming important polities in Ndebele society. An example of this was the Venda chief Tibela who sought refuge from Mzilikazi after constant harassment from Swazi raiders. Tibela was made into one of the king’s intelligence agents. One of the distinguishing characteristics of this group of Hole is that they were bi-lingual, speaking both their mother tongue, and siNdebele.

The other group of Hole comprised of captives and young men supplied by the subject chiefs for the Ndebele army. It was acceptable for Ndebele soldiers to bring back captives from their raids and these captives were incorporated into Ndebele society either as wives of Ndebele soldiers or slaves. It is estimated that by the fall of the Ndebele state in 1893, there were three times as many Hole as were the Zansi and Enhla combined, showing the success of the Ndebele’s policy of assimilation.

Undoubtedly, this huge class of Ndebele came to have a big influence on the Ndebele culture, an influence that is evident even today. In the modern day Ndebele society these demarcations exist, but as strongly as they did by the fall of the Ndebele kingdom.

Victoria Falls,Matebeleland,Zimbabwe

Culture and Religious beliefs of the Ndebele Tribe

The Ndebele state was divided into three social groups, the Zansi, Enhla and Hole. Due to the social intermingling of the various classes / groups in Ndebele society, Ndebele religious and cultural practice became a hybrid of the beliefs and practices of the various peoples that made up the society. However it is important to give a profile of Ndebele culture as a product of cultural practice in Zululand. This was the practice of the Zansi, the original Ndebele who left Zululand with Mzilikazi.

Ndebele culture was centred on certain religious rituals. The king was regarded as the High priest of the nation, and unlike in Shona culture, Ndebele chiefs had no ritual functions beyond functioning as priests of their households and their extended families. Communication with the supernatural on problems such as droughts and epidemics was thus limited to the king only.

It must be noted that as the custodians of true Ndebele culture, the Zansi were unable check the influence of the Enhla and Hole on their beliefs and practices. The Hole had some similarities with the Zansi, but the greatest religious change to Ndebele society was the acceptance of the Mwari cult into Ndebele cultural beliefs and practice.

By and large, the Ndebele believed in a creator, uNkulunkulu (uMlimo) thought of as the first human being. Nkulunkulu and his wife, Mvelengani are said to have emerged out of a marshy place where they found cattle and grain already awaiting them in abundance. They lived together and had children to whom they passed on their culture and tradition, when they were old, they returned to the ground where they became snakes.

The Zansi, like the Nguni, had a notion of a high deity linked with the heavens, but no rituals were celebrated to this high god, as he was not distinguishable from the first ancestor who lived in the ground. However through possible influence from Christianity, Sotho-Tswana beliefs and Shona religion, the Zansi have come to insist that although they worshiped ancestral spirits directly, the spirits also acted as intercessors between the living and their high god. Zansi religious activity therefore centred around the worship of the ancestral spirits whom were called amadlozi.

The Zansi also conceived of man as made up of three aspects, the material and two spiritual beings. They believed that from birth to death, a person lived with a spirit, which looked after him and could bring good fortune of misfortune to him. This spirit was also called idlozi and a fine line of distinction existed between this spirit and the one that passed onto the ancestral world.

Amadlozi were considered very powerful and they had an active interest in the welfare of their living relatives. They required of the living to maintain proper relationships with them and wrong doers were sometimes severely punished. Amadlozi also secured their relatives from witchcraft and harmful magic.

Amadlozi had a hierarchy of their own just like their living relations. Each Zansi lineage and family had its own amadlozi and the most senior member of the family acted as the high priest. However amadlozis powers were limited to issues to do with their own relatives. Only the king`s amadlozi exercised national guardianship.

The most important rites associated with family ancestral spirits were the Ukuhlanziswa (cleansing) and Ukubuyisa (bringing home) ceremonies. The Zansi believed that death brought bad bad omen to the nearest living relatives of the deceased and such an omen could be passed on to neighbors, so it was necessary for the family to be cleansed soon after burying the deceased.

When a year had elapsed, the deceased spirit, which had been roaming around homelessly, manifested itself to the family in the form of a snake, dreams or sickness to one of the relatives. The family would then respond with a bringing home ceremony where the most senior of the relatives officiated. An ox was sacrificed during the ceremony.

The priest prayed to the spirit, now called idlozi, and the ox`s meat was left over night for the idlozi to eat. In the morning, a feast would be held to eat the meat and drink beer brewed for the ceremony, people feasted as guests to the spirit and after the ceremony, the idlozi joined the other ancestral spirits and became an object of worship.

Matebeleland dancers

In general the Zansi lived their lives under the guidance of amadlozi and no dangerous action was taken with asking for protection and luck from the ancestors. Such supplication was done through the offering of an ox and a prayer to the ancestors. A similar fashion of ancestral worship prevailed at national level only that it was done on a grander and more elaborate scale.

The most important religious festival was the annual Inxwala festival. Here the king prayed and sacrificed as many as fifty oxen to his amadlozi for national prosperity, welfare and victory over enemies. In time of drought, the king also led in rain making ceremonies conducted as the royal graveyards. These ceremonies were known as Ukucela Imvula emakhosini.

ndebele woman

Mural paintings:The Ndebele have unique practice of decorating their home with colourful murals. These designs are passed from one generation to another and from mother to daughter.

Ndebele painting

The distinctive styles have symbolic meanings associated with their lives. Traditionally the houses were painted in mute natural colours but, since the introduction of Indian and Western influences, the pigments are now much brighter.

Ndebele people.South Africa

Praise poetry: Praise poetry is a form of poetry that evolved from the desire to commend the achievements of the leader of the tribe A special person called an imbongi is given the task of reciting the poetry to the

leader.

Initiation rites/Music: The (ama)Ndebele of Zimbabwe, unlike ama Ndebele of South Africa, do not practice this so-called circumcision initiation rites of boys (known as ukuwela ‘to cross over (the river)’ and girls (known as ukuthomba ‘to reach the age of puberty’ in Southern Ndebele).

Instead, they hold an annual national religious festival called inxwala ‘first fruit festival’ (Ndlovu, 2009:109). The Inxwala ceremony is associated with the (ama)Swati tradition and culture for the female ceremony. This gives evidence that Mzilikazi and his people left KwaZulu when Shaka had already terminated the circumcision cultural practice amongst the Zulu tribe.

Isitshikitsha is a Ndebele tribal dance, the dance was brought into Zimbabwe by the Ndebele people who migrated from South Africa under the great King Umzilikazi kaMatshobana. The Ndebele people settled in the Southern parts of Zimbabwe near the city of Bulawayo. Isitshikitsha was basically meant as entertainment for social gatherings such as wedding ceremonies or during the first fruits ceremony known as Inxwala. The dance is accompanied by clapping, ululation and whistling.

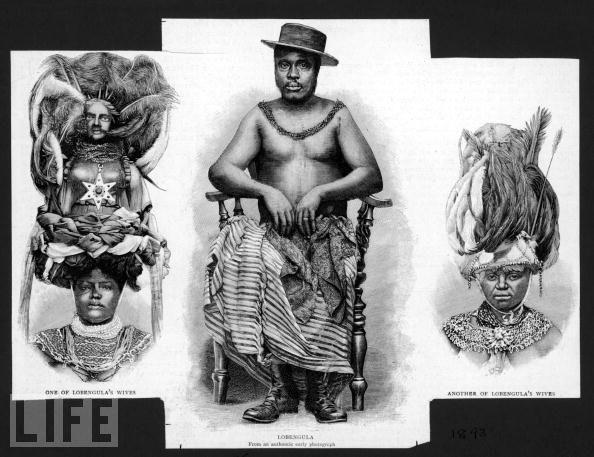

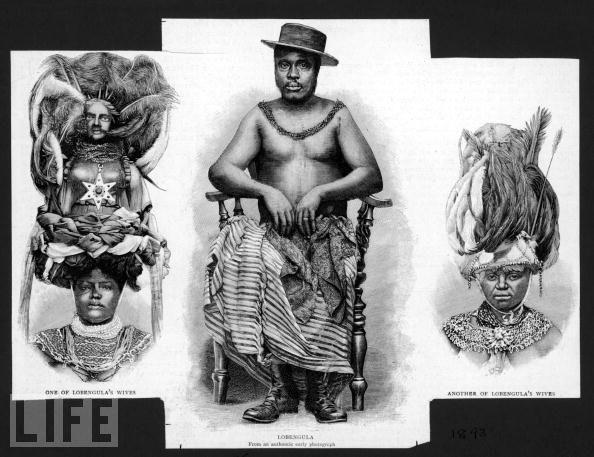

KING LOBENGULA KHUMALO, THE FLY OF ZIMBABWE, KING OF MATABELE, THE SECOND AND LAST SOUTH AFRICAN NDEBELE KING WHOM THE BRITISH USED HIS AFFECTION FOR CHRISTIANITY TO DESTROY HIS EMPIRE AND STEAL HIS GOLD AND DIAMONDS

Lobengula, "He who was sick", was the son of Mzilikazi, son of Matshobana, son of Mangete, son of Ngululu, son of Langa, son of Zimangele; all descendants of the Khumalo Dynasty. Lobengula is mother was a Princess of the Swazi House of Sobhuza I. Lobengula ruled the Matebele Kingdom from the time of the death of Mzilikazi 1868, until the demise of the Kingdom in the Mid 1890's.

Lobengula was in some ways lucky to have lived long enough to ascend to the throne. It is said that, Lobengula and Nkulumane along with their mothers were sentenced to death by their father, Mzilikazi. But however, Mncumbatha Khumalo felt pity for him, released him and instructed him to go and hide. Mncumbatha Khumalo returned and told the King that he had followed his (the King) directive. The King eventually found out, and had mercy on Lobengula, but he didnt want Lobengula to enter his court yard. One of the Chief was asked to take care of Lobengula, as a result Lobengula did not get first hand experience of how state affairs are run.

On September 12 1868, King Mzilikazi of the Ndebele state died and his remains were put in a cave at Entumbane, on the northern peripheries of the Matopo Hills. After some debates, disagreement and agreements the throne was given to Lobengula.

A section of the Ndebele nation, however, was opposed to Lobengula, possibly stirred up by some instances by other members of the royal family who wished to have the crown for themselves, refused to accept any king but Nkulumane. The section argued that Lobengula was born of Swazi woman, and therefore could not ascend to the throne. It was easy to see, therefore, that there was but one way to decide the question, - a fearful battle was to be fought between the two opposing parties.

The result of the battle was that Lobengula and the warriors supporting him gained the victory, and the rebels were crushed, so much so, that they consented to Lobengula becoming king without further protests. According to Ndebele custom, a new king had to establish his own royal palace and town. Consequently, Lobengula left King Mzilkazi's last capital of Mhlahlandlela to establish his own town, which eventually became known as Bulawayo.

Mzilikaziâ`s friendship with Robert Moffat was a most significant influence in the fate of his Kingdom after his reign. Mzilikazi had very little time for Christianity, but because of his respect for and trust of Moffat he allowed himself to be persuaded to admit the Matebele mission to his realm. Once established there he and his successor Lobengula always gave protection to the missionaries. Lobengula reigned well and entertained Europeans sparingly, one recorded account is that J.C. Chadwick. J. Cooper Chadwick in his book THREE YEARS WITH LOBENGULA (London, Cassell, 1894, 160pp) writes: "The King is by far the most intelligent man in the nation and his memory is marvelous".

Lobengula's sympathies and soft spot for the missionaries which he had inherited from his Father, King Mzilikazi, eventually led to the downfall of the Matebele Kingdom. Lobengula's Kingdom, encompassed both Matebeleland and Mashonaland, but this country was rich in natural resources, which was the interest of European Settlers. Through the various concessions and treaties, Lobengula was tricked into signing over his Kingdom to the authority of Cecil John Rhodes.

Of all the concessions, the most critical was the Rudd Concession, setting the stage for Rhodes British South Africa Company to mastermind the coup de grace in the form of the Rudd Concession. The Rudd Concession conferred sweeping commercial and legal powers on Rhodes. Furthermore to in order to weaken any possible resolve on Lobengula`s part, scouts in the Rudd party secretly agitated the neighboring Shona, who believed that the emerging problems were precipitated by the Matebele.

Lobengula mounted a number of armed attempts to counter the takeover of his nation. In July 1893, the Matebele War broke out when a party of Lobengula`s warriors raided a Mashona village near Fort Victoria (now Masvingo), threatening a camp of British settlers. The British High Commissioner authorized the then present military force to respond and indeed to continue the advance until all of Matebeleland was occupied and under strict British Control.

Lobengula and a small remnant of his once powerful Impi were driven to a point approximately seventy kilometers north of the Zambesi River. Sir James McDonald, in his book RHODES“ A LIFE (London: Philip Allan 1928, 403pp) describes the now very ill Lobengula`s last hours: "He felt his end was near, and calling together those faithful indunas and warriors who still remained with him, he said. . . go now all of you to Rhodes and seek his protection. He will be your chief and friend. To the fighting men present he said :You have done your best, my soldiers; you can help me no more. I thank you all. Go now to your kraals and Mjan (the General of all of Lobengula`s Impi) the greatest of you all, will go to Rhodes, who will make things all right for you. To all of you I say "Hambani kuhle“ go in peace!" Before twenty-four hours had elapsed, Lobengula was no more and Mjan. . . in due course reached Bulawayo and gave this account of his last hours.

HOW CECIL RHODE USED THE CHRISTIAN MISSIONERIES TO DISINHERIT LOBENGULA AND HIS ZAMBIAN (MATEBELE) NATION.

"The British happens to be the best people in the world, with the highest ideals of decency and justice and liberty and peace, and the more of the world we inhabit, the better it is for humanity.'—Cecil Rhodes

Cecil John Rhodes

Coming from the south, over what is now known as Botswana, the British worked through Cecil Rhodes to establish themselves in Lobengula's land. Rhodes, then premier of the Cape Colony, wanted to carve out a vast British colony which would stretch from the Cape of Good Hope to Egypt. The railway line he planned to build to link Cape Town and Cairo would run through Ndebele territory. He also wanted a British presence in central Africa, to block Boer movement northward. The Portuguese dreamed of a link between Angola and Mozambique across Ndebele country, and the Germans wanted one between South-West Africa and Tanganyika. From the Congo, the Belgians were pressing southward toward Lobengula's domains. The Boers from the Transvaal had their eyes on the fertile lands on the northern side of the Limpopo.

Imperialist and Capitalist Cecil Rhodes; from Cape Town to Cairo

The British sent a missionary, John Smith Moffat, to Lobengula's court, to keep an eye on British interests. Moffat was the son of a missionary who had made a name for himself among the Botswana to the south. Lobengula welcomed him as a bearer of spiritual tidings. The missionary persuaded the King to sign a treaty with the British, by which Lobengula undertook not to cede land to any power without the consent of the British. Sections of the army opposed the treaty, on the score that it surrendered the sovereignty of the Ndebele to the British. Lobengula believed and argued that the man of God wanted a friendship which would protect that very sovereignty.

Rhodes followed the Moffat maneuver with a delegation to Lobengula, which asked for, and got, permission for Rhodes to trade, hunt, and prospect for precious minerals in Ndebele territory. This came to be known as the Rudd Concession (1888). In return Rhodes offered 1, 000 Martini-Henry rifles, 100, 000 rounds of ammunition, an annual stipend of £1, 200, and a steamboat on the Zambezi. He formed the British South Africa Company to explore the concession, and organized 200 pioneers, promising each a 3, 000-acre farm on Ndebele land, and sent them north with a force of 500 company police.

Rhodes's plans infuriated the Ndebele. Lobengula canceled the concession and ordered the British out of his country. As he had only spears to ensure respect for his commands, the British ignored his order, proceeded to complete the road link with the south, and brought in more settlers.

In August 1889 the King Lobengula wrote to Queen Victoria to complain:

"The white people are troubling me much about gold. If the queen hears that I have given away the whole country it is not so."

Lobengula next tried diplomacy, an art in which he had never excelled. He gave a concession to Edouard Lippert from Johannesburg in the Boer Republic. Lippert was to make an annual payment to Lobengula for a lease which gave him the right to grant, lease, or rent parts of Ndebele land in his name for 100 years. This attempt to play the Boers against the British was Lobengula's undoing. Lippert turned round and sold the concession to the very company Lobengula had expelled. The company cut up Lobengula's land and distributed the promised farms to the pioneers.

The company's British shareholders were pleased with Rhodes's strategy. Encouraged by his victory, Rhodes next planned to extend the railway line from Mafeking northward. This line was to run through Ndebele territory. But by this time, Lobengula and his people were no longer in the mood to allow further incursions into their lands. Rhodes had to start thinking of war.

Matabele women at Cecil Rhodes' farm. A group of Matabele (Ndebele) women pose for the camera outside thatched huts at Cecil Rhodes' farm in Sauerdale. Rhodes bought the farm after negotiating an end to the Matabele rebellion, and settled some Matabele people there in part fulfilment of a promise to provide them with decent land. Near Bulawayo, Rhodesia (Matabeleland North, Zimbabwe), circa 1897., Matabeleland North, Zimbabwe, Southern Africa, Africa.

British telegraph wires were cut near Victoria. The company's police seized the cattle found near the scene of the crime. It turned out that the animals belonged to Lobengula. The Ndebele military clamored for their return. War was averted by the British negotiating a settlement.

While these developments were taking place, the British extended their control over land which Lobengula claimed. Black communities which had owed allegiance to Lobengula were encouraged to come under British rule. This was not difficult to do, because Lobengula had not treated his weaker neighbors with much understanding. It became clear that British intentions and Lobengula's independence were incompatible. War broke out toward the end of 1893. The Ndebele army was crushed, and Lobengula fled northwards and died about a month later.

Imperialist Dr Jameson in Bulawayo. 1893

By 1895, the country was known as Rhodesia, and, since 1980, the independent Republic of Zimbabwe.

source;http://www.northstarfigures.com/matabele.pdf

'Heir to Ndebele throne is found'

THE heir apparent to the Ndebele Kingdom is safe and well in northern South Africa, according to shock new research.

History enthusiast Colls Ndlovu, who is researching a book, claims to have also found the grave of Nkulumane, the first son of King Mzilikazi, who had a brief reign as Ndebele King and has long been thought to have been killed on the orders of his father.

Royal family ... Prince Ngwalongwalo Mzilikazi Khumalo (2nd from left) said to be descendent of Ndebele King

Ngwalongwalo Mzilikazi Khumalo, born on March 13, 1938, told Ndlovu his father, Ndlundluluza Mzilikazi Khumalo, was the son of King Nkulumane.

Nkulumane was installed as King when he became separated from his father who led his tribe from Zululand across the Limpopo River into modern day Zimbabwe in 1838. Mzilikazi’s journey took him to Botswana, where he remained for many years while the group led by Nkulumane settled in Bulawayo.

The group led by Nkulumane gave up the King for dead and hailed his young heir as successor. On his reappearance, Mzilikazi asserted control. Accounts of what followed differ, but it is generally accepted that Mzilikazi ordered Nkulumane to be taken back to Zululand, although another opinion says Nkulumane was executed along with dozens of chiefs who installed him in what is known as Ntabazinduna, just outside Bulawayo.

Mzilikazi died in 1868, and according to the Dictionary of African Historical Biography, he never revealed Nkulumane’s fate “nor did he designate another heir”.

Lobengula was installed as King in 1870 after a delegation he sent to KwaZulu-Natal to look for his half-brother, Nkulumane, searched for a year and could not find him. His ascent to the throne was unpopular with some of Mzilikazi’s decorated troops, notably Mbiko Masuku, who led an uprising which was violently crushed.

Ndlovu was researching a book on ‘The Assassination of King Lobengula’, the last Ndebele King who is believed to have died in 1893, when he stumbled on the tantalising findings.

His research took him to the Phokeng township just outside Rustenburg, in the North West Province of South Africa, where he met Ngwalongwalo, who claims to be a third generation Prince and direct descendent to King Nkulumane.

Discovery ... Colls Ndlovu (left) with a man identified only as George, who says he tends

to a grave believed to be that of Ndebele King Nkulumane

Ndlovu told New Zimbabwe.com from South Africa on Monday: “This is an exciting moment for the Ndebele people and indeed all Zimbabweans. History is being rewritten ... a lot of what we have been told about our history is being proved to be fiction.

“We are now learning about the richness of our culture, and the umbilical link between our people and Zululand.

“We have found Nkulumane’s grave, and found his grandson, our King.”

According to Ndlovu, Ngwalongwalo is “more than ready to go to Zimbabwe” if “his people come forward and ask him to, but he is not going to impose himself. He has not pushed it.”

“His house is within a kilometre from King Nkulumane’s grave, and close to the Royal Bafokeng Palace in Phokeng. The area is known as Nkulumane Park and the people who live there speak Ndebele fluently, including Ngwalongwalo. They call him ‘inkosi yamaNdebele’.”

Ndlovu’s findings appeared to immediately trigger-off a potential power struggle with King Lobengula’s descendents who say the findings, if true, are only of “theoretical interest” and have no significance on any future plans to revive the Kingdom and install a King.

Lobengula’s descendents say because Nkulumane could not be found to take over when King Mzilikazi died in 1868, the crown moved from Nkulumane’s lineage and to the Lobengula clan. Nkulumane and Lobengula had different mothers, the former’s mum, MaNxumalo, considered the senior wife.

Prince Zwide kaLanga Peter Khumalo, who says he is a fifth generation descendent to Mzilikazi, on the Lobengula side, said: “A grave on its own doesn’t authenticate that it is Nkulumane buried there.

“The whites attempted once to set up a decoy in South Africa to pretend it was Nkulumane returning to take over the throne here, it could easily be the grave of that person.

“We need more evidence.”

He said his family would take an interest in the matter “purely from a historical point of view”.

Prince Khumalo added: “There is no thought in the family to prove it beyond technical doubt. Exhuming the body and checking the DNA is culturally not something we are willing to do. We can’t be digging up graves.”

The Prince, who fronted the construction of Old Bulawayo – a restoration of King Mzilikazi’s last royal residence – said the “royal structure moved on from Mzilikazi to Lobengula according to the King’s wishes” and any future monarch would “not go back to Nkulumane.”

He added: “Researchers should not create Kings. In any case, the account of what has been found as you describe is full of factual dislocations.

“If Lobengula became King, he was not a half King. Nkulumane was cursed by his own father. The issue of descendents of Nkulumane does not arise anymore.

“King Lobengula’s children are known, and the descendents of those children are known, here and in South Africa. They are not mysterious. So if ever the Ndebele people woke up tomorrow and said ‘we want a King’, it has to be resurrected where it ended – and that is from King Lobengula and his descendents.”

Ndlovu says his interest is not to see the revival of the Ndebele kingdom but testing some accepted legends about Ndebele royalty, in particular the “disappearance” of Lobengula in 1893.

“We have generally been told that the King disappeared. I will in my book prove that he was sacrilegiously assassinated by the forces of the colonising company. Dr Leander Star Jameson, a colonial army enforcer, immediately set out on his ill-fated Jameson Raid into the North West part of the Transvaal areas.

“Our suspicion was that perhaps Dr Jameson had Prince Nkulumane in mind, now that Lobengula was dead. So we decided to intensify our research in that area of the North West.”

Ndlovu said he was “pleasantly surprised” to discover Nkulumane’s grave which he says will dispel “myths” that he was put to death on the orders of his father, King Mzilikazi.

“It turns out Mzilikazi asked a full regiment to accompany Nkulumane back to Zululand. On his way there, he passed through the Rustenburg area, among the Sotho people, and stayed for sometime.

“As he was about to proceed with his journey south, the tribe was attacked, and Nkulumane rallied his forces and defeated the invading forces. Then the Bafokeng King said ‘stay here, and you will be protecting us and enable the survival of our nation’. He settled there, got married to MaNdiweni and had a family, and a son named Ndlundluluza Mzilikazi."

sourcehttp://www.newzimbabwe.com/news-2082-Heir

Victoria Falls at Matebeleland,Zimbabwe

Victoria Falls is a town in the province of Matabeleland North, Zimbabwe. It lies on the southern bank of the Zambezi River at the western end of the Victoria Falls themselves. It is connected by road and railway to Hwange (109 km away) and Bulawayo (440 km away), both to the south-east.According to the 1982 Population Census, the town had a population of 8,114, this rose to 16,826 in the 1992 census.

Victoria Falls Airport is 18 km south of the town and has international services to Johannesburg and Namibia.The settlement began in 1901 when the possibility of using the waterfall for hydro-electric power was explored, and expanded when the railway from Bulawayo reached the town shortly before the Victoria Falls Bridge was opened in April 1905, connecting Zimbabwe to what is now Zambia. It became the principal tourism centre for the Falls, experiencing economic booms from the 1930s to the 1960s and in the 1980s and early 1990s.Since the late 1990s, due to Zimbabwe's political and economic unrest, the primary tourism base for the Falls has moved mostly across the border to Livingstone, Zambia

Ndebele Poetry

Ndebele Praise poetry (Izibongo Zamakhosi) is poetry that developed as a way of preserving the history of a clan by narrating how it was founded and what its outstanding achievements were. The praises centred on the leader of the clan. As the clans grew into tribes, it was the leader of the tribe who became prominent and hence his praises were sung.

In the Nguni tradition, to which the Ndebele belong, a special person called the Imbongi recited the praises of the leader of the tribe or chief and later of the king. The task of the imbongi was to narrate the leader’s history and focus on his role in the formation of that tribe or nation, hence the poem is referred to as Izibongo Zamakhosi (King’s praises). The imbongi salutes the king and addresses him directly referring to him through images that highlight his bravery, skills, greatness and other positive attributes. Praise poetry uses images drawn from the local environment and from the universe. The following praises of King Mzilikazi illustrate this point:

Albert Nyathi, the famous Matebele poet standing up in the middle

IZIBONGO ZIKAMZILIKAZI KAMATSHOBANA

Bayethe! Hlabezulu!

Untonga yabuy’ ebusweni bukaTshaka.

Utshobatshoba linganoyis’uMatshobana.

Intambo kaMntinti noSimangele-

Isimangele sikaNdaba

Intambo kaMntinti noSimangele,

Abayiphothe bakhal’imvula yeminyembezi.

Ilang’eliphum’endlebeni yendlovu,

Laphum’amakhwez’abikelana.

UMkhatshwa wawoZimangele!

Okhatshwe ngezind’izinyawo,

Nangezimfutshazanyana.

Wal’ukudl’umlenze kwaBulawayo.

Inkubel’abayihlabe ngamanxeba.

Unkomo zavul’inqaba ngezimpondo,

Ngoba zavul’iNgome zahamba.

Inyang’abath’ifil’uzulu

Kant’ithwasile;

Ithwase ngoNyakana kaMpeyana.

Inkom’evele ngobus’emdibini.

Uband’abalubande balutshiy’uZulu.

Inkom’ethe isagodla yeluleka

THE PRAISES OF MZILIKAZI, THE SON OF MATSHOBANA

Bayethe! Ndebele Nation!

You are the knobkerrie that menaced Tshaka.

You are the big one who is as big as his father Matshobana.

You are the string of Mntinti and Simangele

Simangele son of Ndaba.

You are the string of Mntitni and Ndaba

The string they made until they wet tears

You are the sun that rose from the ear of the elephant,

It rose where upon the birds announced to each other.

You are the son of Simangele who was kicked!

Who was kicked by long feet and by the short ones.

You refused to eat the gift of meat in Bulawayo.

You are the fighter who has marks of fighting,

You are the cattle that opened the closed pen with their horns,

Because they opened the Ngome forests and left.

You are the moon the people said had set

Yet it was just rising;

It rose in the year of Mpeyana.

You are the cow that showed its face from the crowd.

You are the log from which the Zulus cut firewood until they left it.

You are the cow that, while it was just emerging made progress.

These praises are better understood if one is familiar with Ndebele history. They tell us how Mzilikazi escaped from Tshaka’s army to establish his own nation, hence “the knobkerrie that menaced Tshaka”. He refused to take part in celebrations at Tshaka’s capital Bulawayo, hence “he refused the gift of meat in Bulawayo”. The imbongi also tells the audience about what people thought of Mzilikazi’s attempts at running away from Tshaka, the great warrior. They thought Mzilikazi would never make any progress hence “the moon they thought had set, yet it had just arisen. It rose in the year of Mpeyana”. Here the image used is that of the old moon disappearing from the horizon. In Ndebele the term used is inyanga ifile, literally meaning, “the moon has died”. Death signifies the end of something, which is what people thought had happened to Mzilikazi. The imbongi contrasts this view with the image of a new moon that has just risen: a very powerful image that dramatises Mzilikazi’s rise to power through his bravery and skill in creating a new nation. The cause of the conflict between Mzilikazi and Tshaka is also referred to through the ‘cows’ that opened the closed cattle pen with their horns and marched through the dark Ngome forests and left Zululand. Again the use of force is suggested through these images referring to the fact that Mzilikazi left Zululand because of the conflict he had with Tshaka over cattle he had captured on a raid. Mzilikazi rose to power in a spectacular manner when it was least expected. The imbongi depicts this through an image of a sun that rises from an elephant’s ear – such an unusual event that the birds had to announce it. Such images are meant to create an impression that will linger in the minds of the audience.

It must be emphasised that Ndebele praise poetry was recited in front of an audience, which was expected to admire and marvel at the achievements of their king. Such a recitation would earn the king the respect of the people who are being reminded of his role in building the nation. The imbongi was, however, at liberty to criticise the king if he thought there was something that was not proper that the king was doing. Mzilikazi’s praises have no criticism largely because he was regarded as a loving and a caring king, unlike his son Lobengula. The latter was criticised for killing his own brothers – (Ingqungqlu emadol’abomvu ngokuguq’engazini zabafowabo: The eagle that has red knees because of kneeling on the blood of his brothers.)

In modern times praises of kings have been composed and recited with the intention of using them to unite a nation against an enemy. Before the Ndebele rebellion of 1896 prominent Ndebele imbongi composed new praises for Lobengula, who had disappeared during the war of 1893. These praises were intended to unite the Ndebele against the British. A few lines from that composition will illustrate the point.

IZIBONGO ZIKA LOBENGULA KAMZILIKAZI KAMATSHOBANA

Ngwalongwalo kaMatshobana!

Watshonaphi, Mzac’omnyama

Otshay’izinkomo lamadoda.

Nkub’enkulu yamahlathi,

Eth’ezinye zitshiy’umzila,

Yona ingatshiyi lasonjwana.

Silwane samahlathi!

Ezinye ziyathungatheka,

Kanti lesi sakwaKhumalo

Sadabula singatshiyi mkhondo.

Amadoda wonke amangele,

Kwaze kwamangala lezinja ezimhlophe

Ukuthi watshonaphi, Khumalo.

Ngangelizwe uyindab’enkulu!

Wal’ukuthunjwa yizizwe

Wakheth’ukuf’ukhulekile

Ithuna lakho liyakwaziwa ngokhokho kuphela, ngangezwe!

THE PRAISES OF LOBENGULA SON OF MZILIKAZI SON OF MATSHOBANA

The owner of many books son of Matshobana

Where did you disappear to, Black Rod

That beats cattle and men?

You the big elephant of the forests,

Whereas other elephants leave a trail,

You do not leave even the smallest trail.

You the lion of the forests!

Whereas other lions can be tracked,

But this one of the Khumalo

Moved across without leaving a scent

All men are surprised

And even the ‘white dogs’ are surprised

About where you disappeared to, Khumalo

You who is as big as the earth you are big news.

You refused to be captured by foreigners

You chose to die a free man

Your grave shall be known by your ancestors only, you who is as big as the earth!

The most significant thing about Lobengula’s praises is the reference to “owner of many books”. This reference is historical as Lobengula was involved in signing so many treaties with white people that his people regarded him as a man of books. During his reign he captured both men and cattle from the tribes that lay outside his kingdom hence the reference to “the black rod that beat cattle and men”. He is described as both an elephant and a lion, the king of the forest. The imbongi continues to give his audience hope for the future by implying that the people must emulate their king who refused to be colonised and chose to die a free man: by emphasising his ability to escape from being captured by the enemy, thus giving this event an heroic interpretation.

In short, for anybody to enjoy and appreciate Ndebele praise poetry it is necessary for them to know Ndebele history. The images that the imbongi uses, although derived from the local environment and the universe, are used in accordance with the role played by the king in the history of his nation. They can only be appreciated and seen to make sense if one has knowledge of that history.

Ndebele traditional dancers performing their tribal Isitshikitsha dance.Bulawayo, Zimbabwe

The northern Ndebele (Northern Ndebele: amaNdebele) /Matebele are a Bantu-speaking nguni people of southwestern Zimbabwe (formerly Matebeleland) who now live primarily around the city of Bulawayo and form 20% of the population of Zimbabwe. By the time of colonial rule, the Ndebele state had existed as a centralised political reality in the south-western part of theZimbabwean plateau with people who were conscious of being Ndebele and who spoke IsiNdebele as their national language (Cobbing 1976; Ndlovu-Gatsheni 2004). The Ndebele existed as an independent nation up to 1893 when King Lobengula was violently removed from power by the British colonialists. They were formerly an offshoot of nguni nation of Natal in Southern Africa, who share a common Ndebele culture and Ndebele language. Their history began when a Zulu chiefdom split from King Shaka in the early 19th century under the leadership of Mzilikazi, a former chief in his kingdom and ally. Under his command the disgruntled Zulus went on to conquer and rule the chiefdoms of the Southern Ndebele. This was where the name and identity of the eventual kingdom was adopted. Mzilikazi originally called his land Mthwakazi and the whites called it Matebeleand.

Beautiful Ndebele girl in traditional dress

During a turbulent period in Nguni and Sesotho-Tswana history known as the Mfecane, Mzilikazi regiment, initially numbering 500 soldiers, moved west towards the present-day city of Pretoria, where they founded a settlement called Mhlahlandlela. They then moved northwards in 1838 into present-day Zimbabwe where they overwhelmed the Rozvi, eventually carving out a home now called Matabeleland and encompassing the west and south-west region of the country. In the course of the migration, large numbers of conquered local clans and individuals were absorbed into the Ndebele nation, adopting the Ndebele language and culture. Historically the assimilated people came from the Southern Ndebele, Swazi, Sotho-Tswana, and amaLozwi/Rozvi ethnic groups.

On the streets of the Zimbabwean city of Bulawayo, a group of men and women commemorate the life of King Mzilikazi, the founder of the Ndebele kingdom, in this shot by Clayton Moyo, who says the annual event is dominated by song and dance.

Today, the (ama)Ndebele of Zimbabwe or bakwaKhumalo (the people of Khumalo) are the second largest population of the country and their language known as isiNdebele, and just like their South African (ama) Ndebele counterpart is one of the official languages of the state.

The Northern Ndebele language, isiNdebele, Sindebele, or Ndebele is an African language belonging to the Nguni group of Bantu languages, and spoken by the Ndebele or Matabele people of Zimbabwe.

isiNdebele is related to the Zulu language spoken in South Africa. This is because the Ndebele people of Zimbabwe descend from followers of the Zulu leader Mzilikazi, who left KwaZulu in the early nineteenth century during the Mfecane.

Ndebele woman dancing on a stage,Bulawayo,Zimbabwe

The Northern and Southern Ndebele languages are not variants of the same language; though they both fall in the Nguni group of Bantu languages, Northern Ndebele is essentially a dialect of Zulu, and the older Southern Ndebele language falls within a different subgroup. The shared name is due to contact between Mzilikazi's people and the original Ndebele, through whose territory they crossed during the Mfecane.

Matebeleland,Zimbabwe

Linguistically, the (ama)Ndebele of South Africa, particularly the Southern (ama)Ndebele, differ radically from their Zimbabwean counterparts. Scholars such as Van Warmelo (1930:7), for instance, state clearly the language of the (ama)Ndebele of South Africa differs from that of Mzilikazi's followers.

Ndebele elder

IsiNdebele of the (ama)Ndebele of South Africa is more influenced by Sepedi because of their close contact for many years, while that of the (ama)Ndebele of Zimbabwe is closer to isiZulu, most probably because they never stayed for long in close contact with the Sotho speaking tribes when they were on their way northwards. The following few lexical examples illustrate differences between the two languages.

IsiNdebele of South Africa IsiNdebele of Zimbabwe English

ihloko Ikhanda ‘head’

ipumulo ikhala ‘nose’

umkghadi ixaba ‘skin blanket’

isiphila ummbila ‘maize’

umsana umfana ‘boy’

umntazana intombazane ‘girl’

ukuluma inxwala ‘first fruit ceremony’

isokana ijaha ‘young man’.

Ndebele man and his wife

Origin

Most Ndebele trace their ancestry to the area that is now called KwaZulu-Natal. The history of the Ndebele people can be traced back to Mafana, their first identifiable chief. Mafana’s son and successor, Mhlanga, had a son named Musi who, in the early 1600’s, decided to move away from his family (later to become the mighty Zulu nation) and to settle in the hills of Gauteng near Pretoria.

Ndebele people of Zimbabwe

After Chief Musi’s death, his eldest son, Manala was named future chief. This was challenged by another senior son, Ndzundza and the group was divided by the resulting squabble between the two. Ndundza was defeated and put to flight. He and his followers headed eastwards, settling in the upper part of the Steelport River basin at a place called KwaSimkhulu, near present-day Belfast, leaving Manala to be made chief of his father’s domain. Two further factions, led by other sons, then broke away from the Ndebele core. The Kekana moved northwards and settled in the region of present-day Zebediela, and the other section, under Dlomo, returned to the east coast from where the Ndebele had originally come.

By the middle of the 19th century, the Kekana had further divided into smaller splinter groups, which spread out across the hills, valleys and plains surrounding present-day Mokopane (Potgietersrus), Zebediela and Polokwane (Pietersburg). These groups were progressively absorbed into the numerically superior and more dominant surrounding Sotho groups, undergoing considerable cultural and social change. By contrast, the descendants of Manala and Ndzundza maintained a more recognisably distinctive cultural identity, and retained a language which was closer to the Nguni spoken by their coastal forebears (and to present-day isiZulu). Hence, the formation of the Southern vs. Northern Ndebele.