THE KONKOMBA PEOPLE: HARDWORKING AGRARIAN AND WARLIKE RULER-LESS TRIBE

"But proud and industrious, oblivious to considerations of status ... the Konkomba are making a useful contribution to the economy of Ghana as well as to their own pockets; their voice will soon be heard and the.. . hierarchy will receive a rougher jolt from these new migrants whom it has rejected than from the old ones whom it has assimilated long since." (Goody 1970: 128)

Konkomba Dancer from Saboba,Northern Ghana

THE Konkomba (also known as Komba) people are hardworking agrarian and warlike Gurma-speaking ethnolinguistic group living in north-eastern half of the Republic of Ghana's 'Northern Region and across the border in the adjacent territory of Kara region, north of Kabou in Togo. Principally about the banks of the Oti river and on the Oti plain north and west of the Basare and Kotokoli hills. The Konkomba are settled in Saboba, Zabzugu and Chereponi areas of Ghana and in Guérin-Kouka, Nawaré, and Kidjaloum areas of Togo (Source: Ethnologue 2010).

The most recently published census data indicates that are approximately 641,000 Konkomba people residing in Ghana and approximately 79,000 in the adjacent border of Togo,making the estimated total population of Konkomba to be 720,000.

Konkomba woman from Zabzugu,Northern Ghana

Konkomba speak of themselves as Bekpokpam, of their language as Lekpokpam, and of their country as Kekpokpam. They are acephalous group of people,making them a tribe without paramount chief or a tribe without ruler. Their neighbours to the west are the Dagomba. This people is known to Konkomba as the Bedagbam; they speak of themselves as Dagbamba, of their language as Dagbane, and of their country as Dagbon. The country is divided into two regions: Tumo, or western Dagomba, and Naja, or eastern Dagomba. The ancient kingdom of Gonja surround the Konkomba from the south- east. They also have a very good relationship with the Mamprusi.

Of all their neighbours the Dagomba are the most important to Konkomba, since it was the Dagomba who expelled them from what is now eastern Dagomba. The story of the invasion is briefly stated by Konkomba and recited at length in the drum chants of Dagomba. I quote a Konkomba elder. "When we grew up and reached our fathers they told us that they (our forefathers) stayed in Yaa [Yendi]. The Kabre and the Bekwom were here. The Dagomba were in Tamale and Kumbungu. The Dagomba rose and mounted their horses. We saw their horses, that is why we rose up and gave the land to the Dagomba. We rose up and got here with the Bekwom. The Bekwom rose up and went across the river. . ."

. . .the Dagomba invasion . . . according to one account, occurred in the early sixteenth century in the reign of Na (Chief) Sitobu.(Tait, David (ed Jack Goody), The Konkombas of Northern Ghana OUP 1961 ).

The Dagbani chiefdoms imposed territorial chiefship upon the Konkomba, exacting tribute and compelling Konkomba compounds to acknowledge the authority of the Dagbani :Vau or paramount chief(Rattray 1932)

Dance troupe from the Konkomba community doing the Konkomba traditional dance called Kinakyu

Konkombas were known to have fomented trouble for the colonial administration; they inflicted so much pain and anguish by the assassinations of German and British soldiers. Froelich says:

“In the face of Konkomba hostility in what is known today as Yendi, the Germans maintained

fortified garrisons at Kidjaboun and Oripi. When relations worsened continuously and at the

least provocation, the Germans pursued the Konkombas, encircled them and exterminated them

mercilessly. At one battle around Iboudou the Konkombas lost more than one thousand

warriors.” (Froelich, J-C. La Tribu Konkomba Du Nord Togo. IFAN-Dakar. 1954. Pp. 4)

The severity of the problems caused by the assertions of the Konkombas – the “unruly clans,” (as often referred to, then and even now), can still be seen today in the severity of the punishments the Germans meted out to the Konkombas. Today, older Konkomba men in their 80s and 90s can still show their right hand-thumbs, severed as proof of the method the Germans and British soldiers used for limiting armed resistance with the archery of the “bow-and-arrow” by the Konkombas.

Konkomba people

Environment

The Konkomba have, for almost five hundred years, occupied the Oti flood plain, a region that suffers from flooding and severe drought. Stretching from the ridges of the Gambaga escarpment down into the northern edge of the Volta region. the Oti plain alternates between swampy fields of red-clay soil and flooded red canyons of impassable crimson mud during the rains and arid dust bowls filled with patches of shrub grass during the dry season. During Harmattan, visibility drops down to a few hundred metres as the sky and the air is thick with airborne sand swept down from the Sahara. Shade temperatures during the vernal day regularly exceed 40 degrees Celsius and only occasion ally does one receive a dose of nocturnal relief from a downpour washed in from the Guinea Coast.

The Konkomba apart from occupying the Northern Ghana, are now scattered and are predominantly settled in the northern Volta where in many communities they are more than the indigenous Guans and Ewes.

Language

Konkomba people speak Lekpokpam, a branch of the Gur linguistic stock, which bears considerable resemblance to that spoken by the neighbouring Mole-Dagbani peoples.

Konkomba people

History and Conflicts with other tribes

The history of where the Konkomba came from to settle in Ghana and Togo is unknown, this makes a lot people to make an ignorant averment that Konkomba people are not from Ghana but are migrants from Togo. What is known however is that Konkomba were already occupying the area called Chare (now Yendi) and Dagombas came to conquer or chased them away. In his book "The Guinea Fowl, Mango and Pito Wars: Episodes in the History of Northern Ghana, 1980-1999 published by Ghana Universities Press, Accra, 2001, N. J. K Brukum aver that . . . the Gonjas under Ndawuri Jakpa defeated Dagbon under Ya Na Dariziogo and compelled the latter to abandon its capital and to move it to its present site, Yendi, which was then a Konkomba town called Chare. The newcomers pushed back the Konkombas and established divisions among them. Despite the assertion of suzerainty, Dagbon seems never to have exercised close control over Konkomba: administration took the form of slave raiding and punitive expeditions. Fynn (1971) asserted 'We know that the ancestors of the Dagomba met a people akin to the Kokomba already living in northern Ghana."

Konkomba war dance

According to (Martin 1976) the Dagomba pushed back the Konkomba and established divisional chiefs among them. The main towns . . . had the character of outposts, strategically located on the east bank of the River Oti...... The Konkomba were by no means assimilated. Relations between them and the Dagomba were distant and hostile: there was little, if any, mixing by marriage. Part of the oral history of the creation of Dagbon suggests that the Dagombas conquered the Konkombas when they moved into the eastern part of the northern region. Whilst acknowledging the encounter the Konkombas on the other hand have vehemently and consistently counter-claimed that they were never in the battle against Dagombas. They insist that they voluntarily moved away from the Dagombas when they arrived. Tait (1961:) quotes Konkomba elder as saying:

"When we grew up and reached our fathers they told us they (our forefathers)

stayed in Yaa (Yendi).The Kabre and Bekwom were there. The Dagomba

in Tamale and Kumbungu. The Dagomba rose and mounted their horses.

We saw the horses, that is why we rose up and gave the land to Dagomba.

We rose up and got here with Bekwom. The Bekwom rose up and went

"across the River." We go, rising up to go "across the river..."

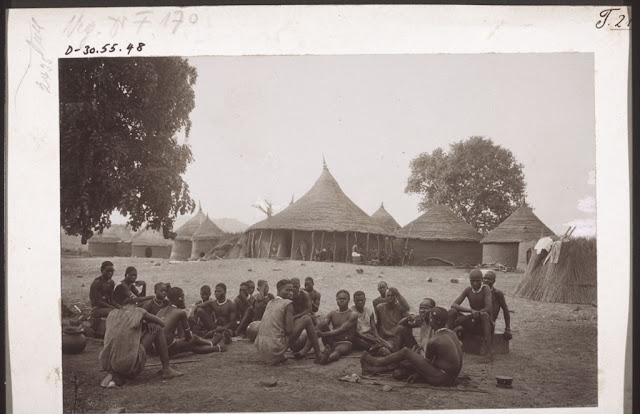

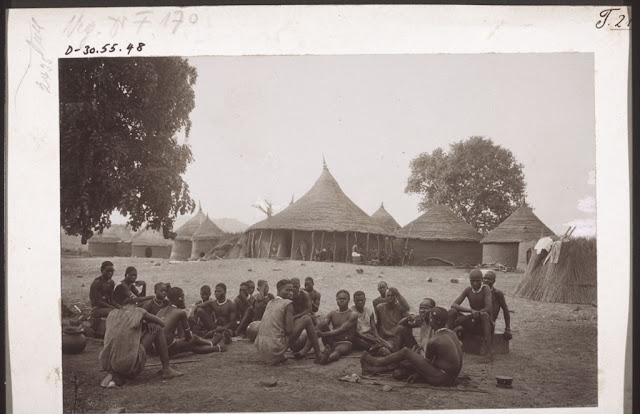

"Konkomba in Tshopowa." Circa 19.03.1910. Courtesy Fisch, Rudolf (Mr)

The Konkomba still regard the earth shrine at Yendi as belonging to them. The entire Konkomba worldview revolves around the earth and that which grows from the soil. Konkomba interviewees explained that the earth of Yendi is kin to the spirits of their ancestors and so in a very concrete way, denial of access to the earth of Konkomba Yendi by the Dagomba is an obstruction to the proper veneration of the an cestors. The Dagomba are aware that the "gods" of Yendi are not of their lineage and

will not attempt to serve the earth and ancestor shrines of Yendi.

"The Dagomba, you know, they can't touch it! The tree, it looks like a

"croc" [crocodile]. They can't do the gods of Yendi because it belongs to

us. Yendi is for us, the earth from Yendi, from the gods, is for us.

Dagomba will Say, afler the war only, Konkomba get power from this

place. (Interview rvith Mr. JB/Tamale. 19/6/1999; the tree he is referring

to is u large Buobab tree on the north side of Yendi)

Dagomba have taken our gods only. But we can't go there and look after

our land. Yendi is for us but they took it from us. And so we must make

our gods somewhere else, but not at Yendi and its not correct, we

shouldn't have to go somewhere else when we know that it is our land.

(Interview with Mr. LN/Sungur. 1 O/8/1999).

The Dagomba invasion had the effect of expelling many Konkomba tiom their

homes; and the mixed ethnic makeup of many Dagomba towns around Yendi suggests that the invaders absorbed or assimilated many others. Along the edge of the Dagornba advance. in areas where Konkomba territory overlapped with that of the Dagomba. the Konkomba were evidently slowly drawn into the structure of Dagomba society. yet remained steadfastly against foreign rule. Under British control. the Dagomba began to appoint Konkomba "liaison" or "sub-chiefs" in the Konkomba areas; however. these individuals possessed little authority throughout the colonial period and still wield only illusory power in the contemporary context. These men were still forced to _gain the approval of the 'elder for the land' before enacting any political decision that might affect the village as a whole, and although the Konkomba had always. through their pattern of dual lineage leadership had two primary eiders within each village. one for the land and one for the people. the individual who spoke for the land, always spoke with authority.

Tait notes that during the 1940s, a Konkomba chief near Saboba was "forced to walk to each hamlet in turn to discuss matters" (Tait 1961: I 1). in a Dagomba village. individuals involved in any decision making process would be forced to visit the palace of the chief and pay their respects. Today, as it was fifty years ago under colonialism, the Konkomba liaison chief still holds the real power. A similar pattern is found in areas where the Konkomba are subjects of other Dagbani paramounts.

To sum up, then, the Konkomba have lived in close proximity with the Dagomba, Mamprusi, Nanumba and Gonja for almost two-hundred and fifty years, and have continuously resisted any movement towards assimilation and incorporation and have been only too well able to strike back at any attempt at subjugation.

Technically, more than half of what is known today as Dagombaland was originally part of Togo when that country was created. It only became part of Ghana at independence. If some Konkombas were carved into Togo alongside many other ethnic groups, why then are they being selectively targeted with migrant argument just to make them look like strangers in the northern territory without any opportunity for land ownership?

This cogent reason and many other injustices perpetrated against the Konkombas as acephalous group, being raided and sold into slavery in the past by the Dagombas, Nunumbas and Gonjas are some of the major reason why Konkombas have had wars in the past and in recent times with all these three ethnic groups.

Perhaps the most devastating example was a forged letter discussing arms supplies, secret meetings and preparations for the conquest of Kpandai and later Yendi, purporting to be an internal communication within the National Liberation Movement of Western Togoland, which was circulated in leaflet form in Tamale and Yendi in 1993. The ‘National Liberation Movement for Western Togoland’ had been a secessionist movement active in the mid-1970s, for a time supported by the Togolese government and allegedly involving some Ghanaian Konkomba. By reviving its spectre the letter sought to portray Konkomba as hostile foreigners, thus neutralising their demand for ‘traditional self-determination’ as citizens of Ghana. Furthermore, its invention of a connection between the Nawuri-Gonja conflict of 1991 with a supposed minority plan to take over Yendi caused the minority majority divide to be seen as the axis of the 1994 conflict.

According to the Dagomba traditional historian Alhaji Gonje Sulamana Al-Hassan, the Dagomba did not believe that there would be an ethnic war with the Konkomba until theadvent of this letter, which led to the connection being made between previous inter-ethnicconflicts and the Konkomba 1993 petitions to the National House of Chiefs and the Ya-Nafor paramountcy. The fear of impending war was seen as having led to the stockpiling of arms on both sides, and inter-ethnic harassment:

"The youth in Yendi town they started harassing the Konkombas every time they

came to market. They started harassing them and warned them: ‘If you come out

against us we are going to let our women catch you with their bare hands’, you

understand? Threatening, ‘We will chain you and we will whip you, we will do

this, and we will do this’. […] So they [the Konkomba] started acquiring arms."

The Kitab Ghunja noted that in about February 1745, "the cursed unbeliever, Opoku Ware, entered the town of Yendi and plundered it." The Ya Na, Gariba, was taken prisoner. When he was being carried to Kumasi, his nephew, Ziblim, the Chief of Nasah, interceded and redeemed him.

Each succeeding Ya Na raided the Konkomba, Basari and Moba in order to obtain captives as slaves to pay the debt. . . . Armed men would descend upon a village at dawn or even during the day. If the raid was successful, they carried away men, women and children and their property like cattle, sheep and goats."

The late 19th century saw two Gonja-Konkomba civil wars (1892-1893, 1895-1896) and one in Dagomba-Konkomba (1888) in addition to raiding by various groups, including the lieutenants of Samory Touré, who was fighting the French, and Babatu, a Zabarima warrior (Ladouceur, 1979). The Konkomba an intermittent pattern of large-scale violent opposition to chiefly demands was started by the attack on the Dagomba village of Jagbel in 1940, sometimes known as the Cow War. The burning of the village and the killing of its chief and members of his family and retinue were precipitated by the chief’s attempt to take advantage of a colonial vaccination programme to collect a bull as a fine from an owner of unvaccinated cattle (Talton, 2003).

The Guinea fowl war broke out in Ghana’s NR and involved the royal Nanumba, Dagomba, and Gonja tribes on one side and the acephalous ‘minority’ Konkomba on the other. The grievances on which this conflict was based were long standing. This episode is best understood as merely the most deadly manifestation of a series of clashes between the cephalous and acephalous tribes of Ghana’s North. Prior to the Guinea Fowl War, violent conflicts occurred between the Mossi and Konkomba in 1993; the Konkomba, Nawuri, Basare, Nchumuru and Gonja in 1992; the Nawuri and Gonja in 1991; the Konkomba and Nanumba in 1981; and the Gonja and Vagalla in Gonja in 1980.

The late 19th century saw two Gonja-Konkomba civil wars (1892-1893, 1895-1896) and one in Dagomba-Konkomba (1888) in addition to raiding by various groups, including the lieutenants of Samory Touré, who was fighting the French, and Babatu, a Zabarima warrior (Ladouceur, 1979). The Konkomba an intermittent pattern of large-scale violent opposition to chiefly demands was started by the attack on the Dagomba village of Jagbel in 1940, sometimes known as the Cow War. The burning of the village and the killing of its chief and members of his family and retinue were precipitated by the chief’s attempt to take advantage of a colonial vaccination programme to collect a bull as a fine from an owner of unvaccinated cattle (Talton, 2003).

The Konkomba became involved in the 1991-1992 Nawuri-Gonja conflict when some of their members were mistaken for Nawuris and shot while working on their Kpandai farmlands. Similarly, the Mabunwura Yakubu Asuma felt that the Gonja had been drawn into the 1994 conflict because of being associated with the other majority groups.

1994 February 2: Fighting in the north near the border with Togo broke out between Konkomba and Dagomba ethnic groups. The incident began with a dispute over prices in a market, but quickly accelerated to large-scale violence. The two groups have been at loggerheads for many years because the Konkomba , who are not Ghanaian natives (My emphasis: this is a highly contentious and provocative statement - see the texts above and J. D. Fage - MH) , are denied chieftainship and land. Only 4 of 15 ethnic groups in the region have land ownership.

1994 February 10: The government issued a state of emergency in the northern region (the districts of Yendi, Nanumba, Gushiegu/Karaga, Saboba/Chereponi, East Gonjo, Zabzugu/Tatale and the town of Tamale). About 6000 Konkomba fled to Togo as a result. The government also closed four of its border posts to prevent the conflict from spreading.

1994 March 4: A grenade exploded in Accra in a Konkomba market injuring three. It is thought to be a spillover from the violence in the north between the Konkomba and Dagomba.

1994 March: The government fired on a crowd in Tamale killing 11 and wounding 18. Security forces fired on mainly Dagomba after they had attacked a group of rival Konkomba . It is difficult for the government to reach Konkomba fighters since they operate in small packets under bush cover.

Members of the Dagomba, Gonjas and Namubas (allies) turned in their arms in compliance with a government order to all warring factions.

The seven districts affected by the fighting are the breadbasket of the region and food prices have increased since the fighting broke out in February.

1994 April: An 11 member government delegation held separate talks with leaders of the warring factions in Accra. Both sides agreed to end the conflict and denounce violence as a means of ending their conflict. The three-month old conflict left over 1000 (one report suggested 6000) people dead and 150,000 displaced.

1994 June 9: A peace pact was signed among all warring factions in the north. Two main groups of disputants were involved in the fighting (Konkomba vs. Dagomba, Nanumba and Gonja) as were several smaller groups (Nawuri, Nchumri, Basari). No incidents were reported in the past several weeks, though the region remained tense.

1994 July 8: Parliament agreed to extend the state of emergency imposed on the 7 northern districts for a further month.

1994 August 8: Parliament revoked the state of emergency officially closing the conflict.

1994 October: Police seized arms bound for the north. The Tamale region is tense and the peace agreement signed in April was regarded as a dead letter. Dagomba communities, backed by the Nanumbas and Gonjas, again began buying arms. Many Konkomba have been keeping out of sight following a series of lynchings.

1995 February 16: Bushfires swept across Ghana causing extensive damage to forests and crops. At least 12 were killed.

1995 March: Renewed ethnic fighting in the north left at least 110 dead and 35 wounded. The Konkombas were largely blamed as instigators of the latest violence. The government had the situation under control by the end of the month. In Nanumba District, five arrests were made in connection to the violence. A total of 25 have been arrested since September 1994 in connection to the violence. Latest casualty figures put the number of dead at 2000 since February 1994, and 400 villages and farms have been burnt to the ground.

1995 June 26: President Rawlings initiated peace talks in parts of the conflict area, praising both sides for their efforts to put aside their differences. Yet, he later issues a warning against the Konkombas in particular to heed reconciliation moves.

1995 November: Tensions were on the rise between Muslims and non-Muslims in areas of Ghana including in the cities of Sekondi and Kumasi. The tensions between the Dagombas and Konkomba , though essentially over land use, were exacerbated by the fact that Dagombas are mainly Muslims while the Konkomba are mainly animist.

Konkomba women

Economy

The konkomba are hardworking farmers. They engaged in large scale production of yams. the farm is the centre of interest in rites and in labour. Within the territory occupied by each Konkomba village there exist a number of different types of farmland known by the crops and the type of agriculture worked on them. A region between two compounds might seasonally be known as yam-land, guinea-corn-land or sorghum-land. The Konkomba allow no land to go uncultivated and village boundaries will extend as far as the closest field of the neighbouring village. Only on the rocky outcroppings that extend into Komba territory From the Gambaga escarpment can one see a break in the land that has been tilled by Konkomba hands.

Konkomba farmer

Some konkomba are into fishing on the Volta lake. They successfully cross other northern natives when the Volta lake gets flooded.

Konkomba fisherman

Supplication of the ancestors commonly takes the form of prayers for rain but they are also asked to keep away the wind. The sudden fierce storms . . . sweep over the open plain. . . break down the corn, tear the roofs off houses, batter down house walls. . . The Konkomba are always on the verge of hunger and only by frugal living can their food be made to last until a new crop is in. The unfortunate thing is that Konkombas do not own the land they cultivate large farms on with their toil. Most of the lands are owned by either Mamprusi,Gonja or their mortal enemies,Dagombas. As a result they are always to make payments to the land owners. This is one of the major reasons why the Konkombas are always fighting to get a paramountcy or chiefs in the they have settled on for many years.

Commercial activities. Most konkombas are yam sellers apart from growing it. They are well-known for their "Yam markets" in the big cities. Konkomba markets are not simply economic ventures but are important social events. Much as people visit the market to buy and trade goods they also visit to meet friends from nearby villages. to drink pito beer and generally enjoy the company of fellow Konkomba. Markets are typicaIly held on a cleared patch of land next ta the road which runs through the village and in addition to the agricultural produce sold by Konkomba farmers to visiting Tchakosi and Bimoba villagers who also set up butcher stalls for the Konkornba to purchase meat products. Other merchants include clothe sellers, foam

mattress salesmen and general vendors of household sundries. Tait notes there are few trade specialists in Konkomba.

Konkomba potter

Ghana`s capital Accra, has its Konkomba Yam Market at the Central business. As deeply earth-deity worshiping, people Konkombas have earth deity in their markets too. The market has an earth shrïne, a small and somewhat defoliated Baobab tree, located in the residential area of the market.

Konkomba women at Saboba market

The Accra market has an earth elder or Utindaan, who oversees all offerings made to this shrine. He also provides approval to a new trader or broker of they wish to set up a new stall in the market. The market Utindaan is the ultimate authority within the market in all matters concerning layout of the market, residential issues, and trader disputes.

The market chairman or Onekpel fixes prices in the market and costs paid by farmers for yam transportation The chairman, assisted by the cooperative board, which is composed of influential and wealthy négociants, sets a standard price for each type of yam according to the supply and demand for particular varieties. The market Onekpel also oversees relations with the numerous Dagomba women who work in the market as

porters for the Konkomba, acting essentially as a liaison between the Konkomba and the Dagomba who are in the employ of market négociants. The position of liaison in the market however, is much changed from the role occupied by the Onekpels co-opted by the Dagbani in times past.

Political and social structures

The konkomba society is an acephalous one. There is no chief. The ‘clan’ and its territorial ‘district’ were the largest Konkomba political units. Clans are made up of major lineages (of five generations) which splintered in minor lineages (three generations) and households and ‘each order of segmentation has its own ritual symbol.’ The Konkomba clan is ‘a morally conscious body’ based on ‘ritual and jural activities’ of an egalitarian gerontocracy of family elders-unikpel (plural:bininkpiib).

Konkomba dancers from Togo

Konkomba political clan autonomy was based on territorial earth rituals to local spirits in territorial ‘districts’: Descendants of the first settlers were eligible as earth priest (otindaa, better spelt utindaan). Konkomba were not capable of organizing on a supra-tribal level, so when Dagomba, with their centralized state structure, invaded the Konkomba territories in the seventeenth century, they picked off the Konkomba ‘clan by clan.’ Because inter-tribal relationships were usually marked by a tense state of reserve, and intra-clan violence was tabooed (tensions were neutralised in joking relations or witchcraft accusations, most Konkomba communal violence were inter-clan feuds. Such feuds could be ceremonially ended between ritually obliged clans (timantotiib).

Konkomba family

Many tribes, but not all, are distinguished by different face marks. Clans of the same tribe stand in ritual partnership and kithship to each other, both relations of ritual assistance. Clans of the same tribe accept the rite of Bi sub tibwar to end a feud. Finally, clans of the same tribe come to each other's assistance in a fight against members of another tribe and there is no end to inter-tribal fighting. We may therefore speak of feud between clans and of war between tribes.

The Konkomba system is one of small, segmented, agnatic clans. Four kinds of group relation unite clans and serve to mitigate hostility between them. At the level of personal relations ties of amity, like those of matrilateral kinship, serve to reduce hostility and help to obviate fights. The relations are: naabo, that between children of one woman; taabo, that between children of one man ; nabo, that between children of the women of one clan ; nato, that, between men married to clan‐sisters ; and dzo, man speaking, or nakwoo, woman speaking, friend.

The naabo tie is stronger and warmer than taabo but both imply reciprocal rights and duties while nabo and nato do not. The basic relation is seen to be naabo which is extended on the principle of the unity of the lineage to give rise to those of nabo and nato. The relation of friendship is the only voluntary one though it is linked with the lover relationship, bwa, the only voluntary relationship between men and women. Friendship often gives rise to marriages and so creates kinship ties which in turn give rise to the relations of amity. All these relationship range widely to cross the boundaries of lineage, clan and tribe.

It is not always possible to distinguish a tribe by the face marks alone. Some of the outlying Konkomba refer to those of the Oti plain as the Bemwatib, the River people. Of these the Betshabob, Bemokpem, Nakpantib and Besangma have the same mark.

No Konkomba knows all the other tribes but most Konkomba know of the Betshabob, the Bemokpem, the Benafiab, the Begbem, the Besangma and the Bekwom. Of these the Betshabob and Bemokpem must each number more than 6,000 and of each some 3,000 live in Ghana on the west bank of the Oti. These are the two largest tribes. The Nakpantib and the Kpaltib number not more than 2,000 each.

There are very wide dialectal variations in Konkomba language. The dialects of the neighbouring Betshabob, Bemokpem, Begbem and Nakpantib are close enough so a speaker of one of them may communicate easily with a speaker of another. Speech between a Betshabob and a Benafiab is difficult even though the tribes are separated at the nearest point by only sixteen miles. Speech between the River people and the Bekwom of northern Gushiego is so difficult that they communicate, when possible, in Dagbane.

Marriage

KONKOMBA practise the betrothal of infant girls to young men in their early twenties who thereafter give bride service and pay bride corn to their parents-in-law, until the girl is of an age to marry. The infant girl is known to the man as his 'wife' (pu); there is no distinction in Konkomba between a 'betrothed girl' and a 'wife'. By 'wife' I shall mean a girl who has joined her husband in his compound and when I use the verb 'to marry' it is as the translation of the Konkomba phrase which means 'to go to the husband'.

When a girl child is born, her parents are approached and given presents of pots of beer and fowls by the parents of a young man of between twenty and twenty-four. Often the parents of the girl receive several offers amongst which to choose. Sometimes the first step is taken by the young man himself who sends a gift of firewood to the mother of the child, who is confined to the room in which the child was born for a week after the birth.

Konkomba little girls washing in a stream

The approach to the parents of the girl is made as soon as the sex of the infant is known. There is often competition between those seeking wives who try, by making large gifts, to persuade the parents to betroth the child to them. There is also competition to send the gifts to the parents as quickly as possible; to this end a young man's sister, herself married into another clan, will not only send speedy word of a female birth to her brother but will even warn him of expected births, so that he can have firewood ready to send to the mother should the child turn out to be a girl.

If the first gifts be accepted then the sender knows that he is being considered as a prospective son-in-law. The gifts should not otherwise be accepted. Some weeks later, in effect when it is clear that the child is likely to live, another pot of beer is sent. When the child is several months old the decision should be made and a son-in-law chosen from among the contestants. An elderly man with children can also be a contestant. The younger brothers of a man may refer to his wife as m pu or “my wife” and she in turn may refer to him

as n tshar “my husband.”

Konkomba woman preparing meal

Religious Belief

To be born into Konkomba society meant following a set of rituals and ceremonies that were an integral part of tribal life and survival. There was no distinction between sacred and secular, spiritual and material, or body and soul. The ‘religious’ was present in every expression of life: work, food, wars, procreation and rest. Atheists were non-existent. Everybody believed in the spirit world and in the fetishes (mountains, trees, rocks and even man-made objects) that represented the various spirits. They also believed in totems: animals or birds that were sacred to the clan.

According to Konkomba religious belief, Uwumbor is the Supreme being, creator of spirits, cosmos and people: the source of all life and moral lawgiver. Man`s soul (nwiin) comes from Uwumbor and after death, it returns to him. Uwumbor is etymologically connected to the word ubor (Ruler). More often Konkomba appealed to beings of a lower other which are close to them.

There are other spirits which are evil too. One of such spirits is Kininbon (Satan), lord of all the evil spirits. The spirits also included the souls of the ancestors who demanded respect and sacrifices in return for

withholding punishment.

The Earth Shrine Worship

In the religious life of the Konkomba, as with many other Guinea coast peoples, earth shrines and the cult of the earth play a crucial role. The earth is the essential medium through which the people of West Africa, people to whom the spirits of the ancestors play a supremely important role in quotidian life, commune with the past and those who went before. The earth is a vital symbol of fertility in the home and in the fields and the ancestors, the ultimate source of sanction for social life for the people of the Northern Territories of Ghana (Manoukian 195 1 : 83).

The Earth Kitik is mother of heavenly god Uwumbor. The personified divinity Kitik is a universal deity of all the Konkomba. It is manifested in the multitude of Earth spirits, protectors of particular clans. The Earth spirits are male or female. Each clan has its own Earth shrine called litingbaln which symbolizes and personifies the local Earth spirit, the protector of all members of a given clan. The Earth shrine is the most important sacred place of the clan and the main center of the Earth cult.The author of the paper presents the names, places and kinds of Earth shrines and provides an interpretation of the ritual performed in the shrine of Earth spirit Naapaa in the village of Bwagbaln. The purpose of the study is to show the social and religious meanings of the Earth shrine in Bwagbaln as the main cult center of five clans of the Bichabob tribe. The source basis was provided first of all by the author's field work conducted among the Konkomba people in the area of Saboba between July 1984 and January 1985 as well as between September 1990 and August 1991.

Konkomba traditional dance

The Earth shrines among the Konkomba usually consist of baobabs and groves. Under the trees and in the groves there are sacrificial stones fulfilling the function of an altar on which offerings are made. The Earth shrines are usually situated in the vicinity of the homesteads or on the border between the arable land and the bush.As opposed to other clan Earth shrines of the Konkomba people, the Earth shrine in Bwagbaln is of clan and supra clan character. As the symbol of the unity of five clans from the Bichabob tribe, it is the most important Earth shrine and the central place of cult the members.The Earth cult of the Konkomba is first of all connected with such seasonal agricultural activities as making preparations for yam planting, corn sowing and for the harvest. The ritual in Bwagbaln was performed on 24 March, 1991, that is in the dry season, before the field work. Its principal aim was to ask for the rain. The ritual performance in Bwagbaln is a condition for beginning the field work in the new agrarian season and it precedes the rituals connected with Earth in the homesteads and Earth shrines in the villages of Nalongni, Kumwateek, Kiteek and Bwakul. The ritual in Bwagbaln had the greatest supra clan range and in that ceremony over 20 elders participated who were representatives of major lineages and clans from Bwagbaln, Saboba, Tilangben, Nalongni, Kiteek, Bwakul (Ghana) and Yoborpu and Lagee (Togo). The participants of the ritual are connected with each other by means of clan community bonds (unibaan), ritual bonds (mantotiib) as well as friendship and neighborhood bonds.

Konkomba village in Togo

Sacrifice-Serving The Shrine

For the Konkomba land is intimately connected with fertility, and the number of pots used in a land rite is always greater than two. Two of the pots are always separated and regarded as the shrine of the twin spirit; twins are seen as symbols of fertile land and of a bountiful harvest to come throughout Gur territory.

Among the Bimotiev one often encounters square clay posts, approximately twenty centimetres in width and half a meter high, in the central yard of a hilly compound or placed in a bush. Upon these posts, calabashes filled with medicine, typically the leaves of germinated seed yams, are placed. These shrines are granted therapeutic and curative powers, they are protective shrines, intended to ensure the well being of village member.

A Stone placed among the boughs of a tree located on the right side of a family compound is thought to symbolize the protective earth spirit of a homestead. A red rooster is sacrificed to this shrine whenever the compound head requires the intervention of a bush spirit whether it be for greater prosperity or increased yields from his yarn mounds (Zimon 1992: 1 1 8)

"Konkomba carriers in Banjeli. The Chief's house." Circa 1910

Death and afterlife beliefs:

Both animal and human spirits interact with the living. Kenjaa are good spirits, kesou are evil. Kesou that plague the living may become kenjaa by being captured at which point they serve as advisors. Typically, the dead join their ancestors, regardless of their crimes, with the exception of sorcerers who’s kin must make sacrifices on his behalf.

Sourcehttp://www.ama.africatoday.com/konkomba.htm

http://www.collectionscanada.gc.ca/obj/s4/f2/dsk3/ftp05/MQ64907.pdf

Konkomba Dancer from Saboba,Northern Ghana

THE Konkomba (also known as Komba) people are hardworking agrarian and warlike Gurma-speaking ethnolinguistic group living in north-eastern half of the Republic of Ghana's 'Northern Region and across the border in the adjacent territory of Kara region, north of Kabou in Togo. Principally about the banks of the Oti river and on the Oti plain north and west of the Basare and Kotokoli hills. The Konkomba are settled in Saboba, Zabzugu and Chereponi areas of Ghana and in Guérin-Kouka, Nawaré, and Kidjaloum areas of Togo (Source: Ethnologue 2010).

The most recently published census data indicates that are approximately 641,000 Konkomba people residing in Ghana and approximately 79,000 in the adjacent border of Togo,making the estimated total population of Konkomba to be 720,000.

Konkomba woman from Zabzugu,Northern Ghana

Konkomba speak of themselves as Bekpokpam, of their language as Lekpokpam, and of their country as Kekpokpam. They are acephalous group of people,making them a tribe without paramount chief or a tribe without ruler. Their neighbours to the west are the Dagomba. This people is known to Konkomba as the Bedagbam; they speak of themselves as Dagbamba, of their language as Dagbane, and of their country as Dagbon. The country is divided into two regions: Tumo, or western Dagomba, and Naja, or eastern Dagomba. The ancient kingdom of Gonja surround the Konkomba from the south- east. They also have a very good relationship with the Mamprusi.

Of all their neighbours the Dagomba are the most important to Konkomba, since it was the Dagomba who expelled them from what is now eastern Dagomba. The story of the invasion is briefly stated by Konkomba and recited at length in the drum chants of Dagomba. I quote a Konkomba elder. "When we grew up and reached our fathers they told us that they (our forefathers) stayed in Yaa [Yendi]. The Kabre and the Bekwom were here. The Dagomba were in Tamale and Kumbungu. The Dagomba rose and mounted their horses. We saw their horses, that is why we rose up and gave the land to the Dagomba. We rose up and got here with the Bekwom. The Bekwom rose up and went across the river. . ."

. . .the Dagomba invasion . . . according to one account, occurred in the early sixteenth century in the reign of Na (Chief) Sitobu.(Tait, David (ed Jack Goody), The Konkombas of Northern Ghana OUP 1961 ).

The Dagbani chiefdoms imposed territorial chiefship upon the Konkomba, exacting tribute and compelling Konkomba compounds to acknowledge the authority of the Dagbani :Vau or paramount chief(Rattray 1932)

Dance troupe from the Konkomba community doing the Konkomba traditional dance called Kinakyu

Konkombas were known to have fomented trouble for the colonial administration; they inflicted so much pain and anguish by the assassinations of German and British soldiers. Froelich says:

“In the face of Konkomba hostility in what is known today as Yendi, the Germans maintained

fortified garrisons at Kidjaboun and Oripi. When relations worsened continuously and at the

least provocation, the Germans pursued the Konkombas, encircled them and exterminated them

mercilessly. At one battle around Iboudou the Konkombas lost more than one thousand

warriors.” (Froelich, J-C. La Tribu Konkomba Du Nord Togo. IFAN-Dakar. 1954. Pp. 4)

The severity of the problems caused by the assertions of the Konkombas – the “unruly clans,” (as often referred to, then and even now), can still be seen today in the severity of the punishments the Germans meted out to the Konkombas. Today, older Konkomba men in their 80s and 90s can still show their right hand-thumbs, severed as proof of the method the Germans and British soldiers used for limiting armed resistance with the archery of the “bow-and-arrow” by the Konkombas.

Konkomba people

Environment

The Konkomba have, for almost five hundred years, occupied the Oti flood plain, a region that suffers from flooding and severe drought. Stretching from the ridges of the Gambaga escarpment down into the northern edge of the Volta region. the Oti plain alternates between swampy fields of red-clay soil and flooded red canyons of impassable crimson mud during the rains and arid dust bowls filled with patches of shrub grass during the dry season. During Harmattan, visibility drops down to a few hundred metres as the sky and the air is thick with airborne sand swept down from the Sahara. Shade temperatures during the vernal day regularly exceed 40 degrees Celsius and only occasion ally does one receive a dose of nocturnal relief from a downpour washed in from the Guinea Coast.

The Konkomba apart from occupying the Northern Ghana, are now scattered and are predominantly settled in the northern Volta where in many communities they are more than the indigenous Guans and Ewes.

Language

Konkomba people speak Lekpokpam, a branch of the Gur linguistic stock, which bears considerable resemblance to that spoken by the neighbouring Mole-Dagbani peoples.

Konkomba people

History and Conflicts with other tribes

The history of where the Konkomba came from to settle in Ghana and Togo is unknown, this makes a lot people to make an ignorant averment that Konkomba people are not from Ghana but are migrants from Togo. What is known however is that Konkomba were already occupying the area called Chare (now Yendi) and Dagombas came to conquer or chased them away. In his book "The Guinea Fowl, Mango and Pito Wars: Episodes in the History of Northern Ghana, 1980-1999 published by Ghana Universities Press, Accra, 2001, N. J. K Brukum aver that . . . the Gonjas under Ndawuri Jakpa defeated Dagbon under Ya Na Dariziogo and compelled the latter to abandon its capital and to move it to its present site, Yendi, which was then a Konkomba town called Chare. The newcomers pushed back the Konkombas and established divisions among them. Despite the assertion of suzerainty, Dagbon seems never to have exercised close control over Konkomba: administration took the form of slave raiding and punitive expeditions. Fynn (1971) asserted 'We know that the ancestors of the Dagomba met a people akin to the Kokomba already living in northern Ghana."

Konkomba war dance

According to (Martin 1976) the Dagomba pushed back the Konkomba and established divisional chiefs among them. The main towns . . . had the character of outposts, strategically located on the east bank of the River Oti...... The Konkomba were by no means assimilated. Relations between them and the Dagomba were distant and hostile: there was little, if any, mixing by marriage. Part of the oral history of the creation of Dagbon suggests that the Dagombas conquered the Konkombas when they moved into the eastern part of the northern region. Whilst acknowledging the encounter the Konkombas on the other hand have vehemently and consistently counter-claimed that they were never in the battle against Dagombas. They insist that they voluntarily moved away from the Dagombas when they arrived. Tait (1961:) quotes Konkomba elder as saying:

"When we grew up and reached our fathers they told us they (our forefathers)

stayed in Yaa (Yendi).The Kabre and Bekwom were there. The Dagomba

in Tamale and Kumbungu. The Dagomba rose and mounted their horses.

We saw the horses, that is why we rose up and gave the land to Dagomba.

We rose up and got here with Bekwom. The Bekwom rose up and went

"across the River." We go, rising up to go "across the river..."

"Konkomba in Tshopowa." Circa 19.03.1910. Courtesy Fisch, Rudolf (Mr)

The Konkomba still regard the earth shrine at Yendi as belonging to them. The entire Konkomba worldview revolves around the earth and that which grows from the soil. Konkomba interviewees explained that the earth of Yendi is kin to the spirits of their ancestors and so in a very concrete way, denial of access to the earth of Konkomba Yendi by the Dagomba is an obstruction to the proper veneration of the an cestors. The Dagomba are aware that the "gods" of Yendi are not of their lineage and

will not attempt to serve the earth and ancestor shrines of Yendi.

"The Dagomba, you know, they can't touch it! The tree, it looks like a

"croc" [crocodile]. They can't do the gods of Yendi because it belongs to

us. Yendi is for us, the earth from Yendi, from the gods, is for us.

Dagomba will Say, afler the war only, Konkomba get power from this

place. (Interview rvith Mr. JB/Tamale. 19/6/1999; the tree he is referring

to is u large Buobab tree on the north side of Yendi)

Dagomba have taken our gods only. But we can't go there and look after

our land. Yendi is for us but they took it from us. And so we must make

our gods somewhere else, but not at Yendi and its not correct, we

shouldn't have to go somewhere else when we know that it is our land.

(Interview with Mr. LN/Sungur. 1 O/8/1999).

The Dagomba invasion had the effect of expelling many Konkomba tiom their

homes; and the mixed ethnic makeup of many Dagomba towns around Yendi suggests that the invaders absorbed or assimilated many others. Along the edge of the Dagornba advance. in areas where Konkomba territory overlapped with that of the Dagomba. the Konkomba were evidently slowly drawn into the structure of Dagomba society. yet remained steadfastly against foreign rule. Under British control. the Dagomba began to appoint Konkomba "liaison" or "sub-chiefs" in the Konkomba areas; however. these individuals possessed little authority throughout the colonial period and still wield only illusory power in the contemporary context. These men were still forced to _gain the approval of the 'elder for the land' before enacting any political decision that might affect the village as a whole, and although the Konkomba had always. through their pattern of dual lineage leadership had two primary eiders within each village. one for the land and one for the people. the individual who spoke for the land, always spoke with authority.

Tait notes that during the 1940s, a Konkomba chief near Saboba was "forced to walk to each hamlet in turn to discuss matters" (Tait 1961: I 1). in a Dagomba village. individuals involved in any decision making process would be forced to visit the palace of the chief and pay their respects. Today, as it was fifty years ago under colonialism, the Konkomba liaison chief still holds the real power. A similar pattern is found in areas where the Konkomba are subjects of other Dagbani paramounts.

To sum up, then, the Konkomba have lived in close proximity with the Dagomba, Mamprusi, Nanumba and Gonja for almost two-hundred and fifty years, and have continuously resisted any movement towards assimilation and incorporation and have been only too well able to strike back at any attempt at subjugation.

Technically, more than half of what is known today as Dagombaland was originally part of Togo when that country was created. It only became part of Ghana at independence. If some Konkombas were carved into Togo alongside many other ethnic groups, why then are they being selectively targeted with migrant argument just to make them look like strangers in the northern territory without any opportunity for land ownership?

This cogent reason and many other injustices perpetrated against the Konkombas as acephalous group, being raided and sold into slavery in the past by the Dagombas, Nunumbas and Gonjas are some of the major reason why Konkombas have had wars in the past and in recent times with all these three ethnic groups.

Perhaps the most devastating example was a forged letter discussing arms supplies, secret meetings and preparations for the conquest of Kpandai and later Yendi, purporting to be an internal communication within the National Liberation Movement of Western Togoland, which was circulated in leaflet form in Tamale and Yendi in 1993. The ‘National Liberation Movement for Western Togoland’ had been a secessionist movement active in the mid-1970s, for a time supported by the Togolese government and allegedly involving some Ghanaian Konkomba. By reviving its spectre the letter sought to portray Konkomba as hostile foreigners, thus neutralising their demand for ‘traditional self-determination’ as citizens of Ghana. Furthermore, its invention of a connection between the Nawuri-Gonja conflict of 1991 with a supposed minority plan to take over Yendi caused the minority majority divide to be seen as the axis of the 1994 conflict.

According to the Dagomba traditional historian Alhaji Gonje Sulamana Al-Hassan, the Dagomba did not believe that there would be an ethnic war with the Konkomba until theadvent of this letter, which led to the connection being made between previous inter-ethnicconflicts and the Konkomba 1993 petitions to the National House of Chiefs and the Ya-Nafor paramountcy. The fear of impending war was seen as having led to the stockpiling of arms on both sides, and inter-ethnic harassment:

"The youth in Yendi town they started harassing the Konkombas every time they

came to market. They started harassing them and warned them: ‘If you come out

against us we are going to let our women catch you with their bare hands’, you

understand? Threatening, ‘We will chain you and we will whip you, we will do

this, and we will do this’. […] So they [the Konkomba] started acquiring arms."

Konkomba drummer from Sambuli,Saboba in Ghana

The Kitab Ghunja noted that in about February 1745, "the cursed unbeliever, Opoku Ware, entered the town of Yendi and plundered it." The Ya Na, Gariba, was taken prisoner. When he was being carried to Kumasi, his nephew, Ziblim, the Chief of Nasah, interceded and redeemed him.

Each succeeding Ya Na raided the Konkomba, Basari and Moba in order to obtain captives as slaves to pay the debt. . . . Armed men would descend upon a village at dawn or even during the day. If the raid was successful, they carried away men, women and children and their property like cattle, sheep and goats."

The late 19th century saw two Gonja-Konkomba civil wars (1892-1893, 1895-1896) and one in Dagomba-Konkomba (1888) in addition to raiding by various groups, including the lieutenants of Samory Touré, who was fighting the French, and Babatu, a Zabarima warrior (Ladouceur, 1979). The Konkomba an intermittent pattern of large-scale violent opposition to chiefly demands was started by the attack on the Dagomba village of Jagbel in 1940, sometimes known as the Cow War. The burning of the village and the killing of its chief and members of his family and retinue were precipitated by the chief’s attempt to take advantage of a colonial vaccination programme to collect a bull as a fine from an owner of unvaccinated cattle (Talton, 2003).

The Guinea fowl war broke out in Ghana’s NR and involved the royal Nanumba, Dagomba, and Gonja tribes on one side and the acephalous ‘minority’ Konkomba on the other. The grievances on which this conflict was based were long standing. This episode is best understood as merely the most deadly manifestation of a series of clashes between the cephalous and acephalous tribes of Ghana’s North. Prior to the Guinea Fowl War, violent conflicts occurred between the Mossi and Konkomba in 1993; the Konkomba, Nawuri, Basare, Nchumuru and Gonja in 1992; the Nawuri and Gonja in 1991; the Konkomba and Nanumba in 1981; and the Gonja and Vagalla in Gonja in 1980.

The late 19th century saw two Gonja-Konkomba civil wars (1892-1893, 1895-1896) and one in Dagomba-Konkomba (1888) in addition to raiding by various groups, including the lieutenants of Samory Touré, who was fighting the French, and Babatu, a Zabarima warrior (Ladouceur, 1979). The Konkomba an intermittent pattern of large-scale violent opposition to chiefly demands was started by the attack on the Dagomba village of Jagbel in 1940, sometimes known as the Cow War. The burning of the village and the killing of its chief and members of his family and retinue were precipitated by the chief’s attempt to take advantage of a colonial vaccination programme to collect a bull as a fine from an owner of unvaccinated cattle (Talton, 2003).

The Konkomba became involved in the 1991-1992 Nawuri-Gonja conflict when some of their members were mistaken for Nawuris and shot while working on their Kpandai farmlands. Similarly, the Mabunwura Yakubu Asuma felt that the Gonja had been drawn into the 1994 conflict because of being associated with the other majority groups.

1994 February 2: Fighting in the north near the border with Togo broke out between Konkomba and Dagomba ethnic groups. The incident began with a dispute over prices in a market, but quickly accelerated to large-scale violence. The two groups have been at loggerheads for many years because the Konkomba , who are not Ghanaian natives (My emphasis: this is a highly contentious and provocative statement - see the texts above and J. D. Fage - MH) , are denied chieftainship and land. Only 4 of 15 ethnic groups in the region have land ownership.

1994 February 10: The government issued a state of emergency in the northern region (the districts of Yendi, Nanumba, Gushiegu/Karaga, Saboba/Chereponi, East Gonjo, Zabzugu/Tatale and the town of Tamale). About 6000 Konkomba fled to Togo as a result. The government also closed four of its border posts to prevent the conflict from spreading.

1994 March 4: A grenade exploded in Accra in a Konkomba market injuring three. It is thought to be a spillover from the violence in the north between the Konkomba and Dagomba.

1994 March: The government fired on a crowd in Tamale killing 11 and wounding 18. Security forces fired on mainly Dagomba after they had attacked a group of rival Konkomba . It is difficult for the government to reach Konkomba fighters since they operate in small packets under bush cover.

Members of the Dagomba, Gonjas and Namubas (allies) turned in their arms in compliance with a government order to all warring factions.

The seven districts affected by the fighting are the breadbasket of the region and food prices have increased since the fighting broke out in February.

1994 April: An 11 member government delegation held separate talks with leaders of the warring factions in Accra. Both sides agreed to end the conflict and denounce violence as a means of ending their conflict. The three-month old conflict left over 1000 (one report suggested 6000) people dead and 150,000 displaced.

1994 June 9: A peace pact was signed among all warring factions in the north. Two main groups of disputants were involved in the fighting (Konkomba vs. Dagomba, Nanumba and Gonja) as were several smaller groups (Nawuri, Nchumri, Basari). No incidents were reported in the past several weeks, though the region remained tense.

1994 July 8: Parliament agreed to extend the state of emergency imposed on the 7 northern districts for a further month.

1994 August 8: Parliament revoked the state of emergency officially closing the conflict.

1994 October: Police seized arms bound for the north. The Tamale region is tense and the peace agreement signed in April was regarded as a dead letter. Dagomba communities, backed by the Nanumbas and Gonjas, again began buying arms. Many Konkomba have been keeping out of sight following a series of lynchings.

1995 February 16: Bushfires swept across Ghana causing extensive damage to forests and crops. At least 12 were killed.

1995 March: Renewed ethnic fighting in the north left at least 110 dead and 35 wounded. The Konkombas were largely blamed as instigators of the latest violence. The government had the situation under control by the end of the month. In Nanumba District, five arrests were made in connection to the violence. A total of 25 have been arrested since September 1994 in connection to the violence. Latest casualty figures put the number of dead at 2000 since February 1994, and 400 villages and farms have been burnt to the ground.

1995 June 26: President Rawlings initiated peace talks in parts of the conflict area, praising both sides for their efforts to put aside their differences. Yet, he later issues a warning against the Konkombas in particular to heed reconciliation moves.

1995 November: Tensions were on the rise between Muslims and non-Muslims in areas of Ghana including in the cities of Sekondi and Kumasi. The tensions between the Dagombas and Konkomba , though essentially over land use, were exacerbated by the fact that Dagombas are mainly Muslims while the Konkomba are mainly animist.

Konkomba women

Economy

The konkomba are hardworking farmers. They engaged in large scale production of yams. the farm is the centre of interest in rites and in labour. Within the territory occupied by each Konkomba village there exist a number of different types of farmland known by the crops and the type of agriculture worked on them. A region between two compounds might seasonally be known as yam-land, guinea-corn-land or sorghum-land. The Konkomba allow no land to go uncultivated and village boundaries will extend as far as the closest field of the neighbouring village. Only on the rocky outcroppings that extend into Komba territory From the Gambaga escarpment can one see a break in the land that has been tilled by Konkomba hands.

Konkomba farmer

Some konkomba are into fishing on the Volta lake. They successfully cross other northern natives when the Volta lake gets flooded.

Konkomba fisherman

Supplication of the ancestors commonly takes the form of prayers for rain but they are also asked to keep away the wind. The sudden fierce storms . . . sweep over the open plain. . . break down the corn, tear the roofs off houses, batter down house walls. . . The Konkomba are always on the verge of hunger and only by frugal living can their food be made to last until a new crop is in. The unfortunate thing is that Konkombas do not own the land they cultivate large farms on with their toil. Most of the lands are owned by either Mamprusi,Gonja or their mortal enemies,Dagombas. As a result they are always to make payments to the land owners. This is one of the major reasons why the Konkombas are always fighting to get a paramountcy or chiefs in the they have settled on for many years.

Commercial activities. Most konkombas are yam sellers apart from growing it. They are well-known for their "Yam markets" in the big cities. Konkomba markets are not simply economic ventures but are important social events. Much as people visit the market to buy and trade goods they also visit to meet friends from nearby villages. to drink pito beer and generally enjoy the company of fellow Konkomba. Markets are typicaIly held on a cleared patch of land next ta the road which runs through the village and in addition to the agricultural produce sold by Konkomba farmers to visiting Tchakosi and Bimoba villagers who also set up butcher stalls for the Konkornba to purchase meat products. Other merchants include clothe sellers, foam

mattress salesmen and general vendors of household sundries. Tait notes there are few trade specialists in Konkomba.

Konkomba potter

Ghana`s capital Accra, has its Konkomba Yam Market at the Central business. As deeply earth-deity worshiping, people Konkombas have earth deity in their markets too. The market has an earth shrïne, a small and somewhat defoliated Baobab tree, located in the residential area of the market.

Konkomba women at Saboba market

The Accra market has an earth elder or Utindaan, who oversees all offerings made to this shrine. He also provides approval to a new trader or broker of they wish to set up a new stall in the market. The market Utindaan is the ultimate authority within the market in all matters concerning layout of the market, residential issues, and trader disputes.

The market chairman or Onekpel fixes prices in the market and costs paid by farmers for yam transportation The chairman, assisted by the cooperative board, which is composed of influential and wealthy négociants, sets a standard price for each type of yam according to the supply and demand for particular varieties. The market Onekpel also oversees relations with the numerous Dagomba women who work in the market as

porters for the Konkomba, acting essentially as a liaison between the Konkomba and the Dagomba who are in the employ of market négociants. The position of liaison in the market however, is much changed from the role occupied by the Onekpels co-opted by the Dagbani in times past.

Political and social structures

The konkomba society is an acephalous one. There is no chief. The ‘clan’ and its territorial ‘district’ were the largest Konkomba political units. Clans are made up of major lineages (of five generations) which splintered in minor lineages (three generations) and households and ‘each order of segmentation has its own ritual symbol.’ The Konkomba clan is ‘a morally conscious body’ based on ‘ritual and jural activities’ of an egalitarian gerontocracy of family elders-unikpel (plural:bininkpiib).

Konkomba dancers from Togo

Konkomba political clan autonomy was based on territorial earth rituals to local spirits in territorial ‘districts’: Descendants of the first settlers were eligible as earth priest (otindaa, better spelt utindaan). Konkomba were not capable of organizing on a supra-tribal level, so when Dagomba, with their centralized state structure, invaded the Konkomba territories in the seventeenth century, they picked off the Konkomba ‘clan by clan.’ Because inter-tribal relationships were usually marked by a tense state of reserve, and intra-clan violence was tabooed (tensions were neutralised in joking relations or witchcraft accusations, most Konkomba communal violence were inter-clan feuds. Such feuds could be ceremonially ended between ritually obliged clans (timantotiib).

Konkomba family

Many tribes, but not all, are distinguished by different face marks. Clans of the same tribe stand in ritual partnership and kithship to each other, both relations of ritual assistance. Clans of the same tribe accept the rite of Bi sub tibwar to end a feud. Finally, clans of the same tribe come to each other's assistance in a fight against members of another tribe and there is no end to inter-tribal fighting. We may therefore speak of feud between clans and of war between tribes.

The Konkomba system is one of small, segmented, agnatic clans. Four kinds of group relation unite clans and serve to mitigate hostility between them. At the level of personal relations ties of amity, like those of matrilateral kinship, serve to reduce hostility and help to obviate fights. The relations are: naabo, that between children of one woman; taabo, that between children of one man ; nabo, that between children of the women of one clan ; nato, that, between men married to clan‐sisters ; and dzo, man speaking, or nakwoo, woman speaking, friend.

Hardworking Konkomba women

The naabo tie is stronger and warmer than taabo but both imply reciprocal rights and duties while nabo and nato do not. The basic relation is seen to be naabo which is extended on the principle of the unity of the lineage to give rise to those of nabo and nato. The relation of friendship is the only voluntary one though it is linked with the lover relationship, bwa, the only voluntary relationship between men and women. Friendship often gives rise to marriages and so creates kinship ties which in turn give rise to the relations of amity. All these relationship range widely to cross the boundaries of lineage, clan and tribe.

It is not always possible to distinguish a tribe by the face marks alone. Some of the outlying Konkomba refer to those of the Oti plain as the Bemwatib, the River people. Of these the Betshabob, Bemokpem, Nakpantib and Besangma have the same mark.

No Konkomba knows all the other tribes but most Konkomba know of the Betshabob, the Bemokpem, the Benafiab, the Begbem, the Besangma and the Bekwom. Of these the Betshabob and Bemokpem must each number more than 6,000 and of each some 3,000 live in Ghana on the west bank of the Oti. These are the two largest tribes. The Nakpantib and the Kpaltib number not more than 2,000 each.

There are very wide dialectal variations in Konkomba language. The dialects of the neighbouring Betshabob, Bemokpem, Begbem and Nakpantib are close enough so a speaker of one of them may communicate easily with a speaker of another. Speech between a Betshabob and a Benafiab is difficult even though the tribes are separated at the nearest point by only sixteen miles. Speech between the River people and the Bekwom of northern Gushiego is so difficult that they communicate, when possible, in Dagbane.

Marriage

KONKOMBA practise the betrothal of infant girls to young men in their early twenties who thereafter give bride service and pay bride corn to their parents-in-law, until the girl is of an age to marry. The infant girl is known to the man as his 'wife' (pu); there is no distinction in Konkomba between a 'betrothed girl' and a 'wife'. By 'wife' I shall mean a girl who has joined her husband in his compound and when I use the verb 'to marry' it is as the translation of the Konkomba phrase which means 'to go to the husband'.

Konkomba woman

When a girl child is born, her parents are approached and given presents of pots of beer and fowls by the parents of a young man of between twenty and twenty-four. Often the parents of the girl receive several offers amongst which to choose. Sometimes the first step is taken by the young man himself who sends a gift of firewood to the mother of the child, who is confined to the room in which the child was born for a week after the birth.

Konkomba little girls washing in a stream

The approach to the parents of the girl is made as soon as the sex of the infant is known. There is often competition between those seeking wives who try, by making large gifts, to persuade the parents to betroth the child to them. There is also competition to send the gifts to the parents as quickly as possible; to this end a young man's sister, herself married into another clan, will not only send speedy word of a female birth to her brother but will even warn him of expected births, so that he can have firewood ready to send to the mother should the child turn out to be a girl.

If the first gifts be accepted then the sender knows that he is being considered as a prospective son-in-law. The gifts should not otherwise be accepted. Some weeks later, in effect when it is clear that the child is likely to live, another pot of beer is sent. When the child is several months old the decision should be made and a son-in-law chosen from among the contestants. An elderly man with children can also be a contestant. The younger brothers of a man may refer to his wife as m pu or “my wife” and she in turn may refer to him

as n tshar “my husband.”

Konkomba woman preparing meal

Religious Belief

To be born into Konkomba society meant following a set of rituals and ceremonies that were an integral part of tribal life and survival. There was no distinction between sacred and secular, spiritual and material, or body and soul. The ‘religious’ was present in every expression of life: work, food, wars, procreation and rest. Atheists were non-existent. Everybody believed in the spirit world and in the fetishes (mountains, trees, rocks and even man-made objects) that represented the various spirits. They also believed in totems: animals or birds that were sacred to the clan.

Konkomba Yam festival

According to Konkomba religious belief, Uwumbor is the Supreme being, creator of spirits, cosmos and people: the source of all life and moral lawgiver. Man`s soul (nwiin) comes from Uwumbor and after death, it returns to him. Uwumbor is etymologically connected to the word ubor (Ruler). More often Konkomba appealed to beings of a lower other which are close to them.

There are other spirits which are evil too. One of such spirits is Kininbon (Satan), lord of all the evil spirits. The spirits also included the souls of the ancestors who demanded respect and sacrifices in return for

withholding punishment.

Konkomba people

The Earth Shrine Worship

In the religious life of the Konkomba, as with many other Guinea coast peoples, earth shrines and the cult of the earth play a crucial role. The earth is the essential medium through which the people of West Africa, people to whom the spirits of the ancestors play a supremely important role in quotidian life, commune with the past and those who went before. The earth is a vital symbol of fertility in the home and in the fields and the ancestors, the ultimate source of sanction for social life for the people of the Northern Territories of Ghana (Manoukian 195 1 : 83).

The Earth Kitik is mother of heavenly god Uwumbor. The personified divinity Kitik is a universal deity of all the Konkomba. It is manifested in the multitude of Earth spirits, protectors of particular clans. The Earth spirits are male or female. Each clan has its own Earth shrine called litingbaln which symbolizes and personifies the local Earth spirit, the protector of all members of a given clan. The Earth shrine is the most important sacred place of the clan and the main center of the Earth cult.The author of the paper presents the names, places and kinds of Earth shrines and provides an interpretation of the ritual performed in the shrine of Earth spirit Naapaa in the village of Bwagbaln. The purpose of the study is to show the social and religious meanings of the Earth shrine in Bwagbaln as the main cult center of five clans of the Bichabob tribe. The source basis was provided first of all by the author's field work conducted among the Konkomba people in the area of Saboba between July 1984 and January 1985 as well as between September 1990 and August 1991.

Konkomba traditional dance

The Earth shrines among the Konkomba usually consist of baobabs and groves. Under the trees and in the groves there are sacrificial stones fulfilling the function of an altar on which offerings are made. The Earth shrines are usually situated in the vicinity of the homesteads or on the border between the arable land and the bush.As opposed to other clan Earth shrines of the Konkomba people, the Earth shrine in Bwagbaln is of clan and supra clan character. As the symbol of the unity of five clans from the Bichabob tribe, it is the most important Earth shrine and the central place of cult the members.The Earth cult of the Konkomba is first of all connected with such seasonal agricultural activities as making preparations for yam planting, corn sowing and for the harvest. The ritual in Bwagbaln was performed on 24 March, 1991, that is in the dry season, before the field work. Its principal aim was to ask for the rain. The ritual performance in Bwagbaln is a condition for beginning the field work in the new agrarian season and it precedes the rituals connected with Earth in the homesteads and Earth shrines in the villages of Nalongni, Kumwateek, Kiteek and Bwakul. The ritual in Bwagbaln had the greatest supra clan range and in that ceremony over 20 elders participated who were representatives of major lineages and clans from Bwagbaln, Saboba, Tilangben, Nalongni, Kiteek, Bwakul (Ghana) and Yoborpu and Lagee (Togo). The participants of the ritual are connected with each other by means of clan community bonds (unibaan), ritual bonds (mantotiib) as well as friendship and neighborhood bonds.

Konkomba village in Togo

Sacrifice-Serving The Shrine

For the Konkomba land is intimately connected with fertility, and the number of pots used in a land rite is always greater than two. Two of the pots are always separated and regarded as the shrine of the twin spirit; twins are seen as symbols of fertile land and of a bountiful harvest to come throughout Gur territory.

Among the Bimotiev one often encounters square clay posts, approximately twenty centimetres in width and half a meter high, in the central yard of a hilly compound or placed in a bush. Upon these posts, calabashes filled with medicine, typically the leaves of germinated seed yams, are placed. These shrines are granted therapeutic and curative powers, they are protective shrines, intended to ensure the well being of village member.

A Stone placed among the boughs of a tree located on the right side of a family compound is thought to symbolize the protective earth spirit of a homestead. A red rooster is sacrificed to this shrine whenever the compound head requires the intervention of a bush spirit whether it be for greater prosperity or increased yields from his yarn mounds (Zimon 1992: 1 1 8)

"Konkomba carriers in Banjeli. The Chief's house." Circa 1910

Death and afterlife beliefs:

Both animal and human spirits interact with the living. Kenjaa are good spirits, kesou are evil. Kesou that plague the living may become kenjaa by being captured at which point they serve as advisors. Typically, the dead join their ancestors, regardless of their crimes, with the exception of sorcerers who’s kin must make sacrifices on his behalf.

Sourcehttp://www.ama.africatoday.com/konkomba.htm

http://www.collectionscanada.gc.ca/obj/s4/f2/dsk3/ftp05/MQ64907.pdf

i am so flattered about this piece of write up!

ReplyDeletethough the writer is not a konkomba person but the way he presented his findings is very very amazing..........

however there are certain educated illiterates who feel they can post any chaff at all about konkombas..........and this kind of hatred and misconception is tarnishing our image...

Thank you Ishmael Tilayah,

ReplyDeleteI particularly like this post because of the documented references made to most of the writer's assertions. That makes the research quite authentic and factual. The writer has been objective as much as he could and the write-up is devoid of bais. Criticism came where needed, and commendations came at appropriate instances. Thanks. But I will simply add that I didn't see anything on standard of education amongst konkombas. perhaps, the time period of the research would have shown very little progress in education. But in 2013, and for the next decade, Konkombas who were mostly seen as uneducated and 'uncivilised' people will occupy top-most positions in various institutions in Ghana and abroad. That is a projection based on the current trends in education. WE ARE COMING UP, and the world should expect much from the one time marginalised ethnic group.

ReplyDeleteI am impressed by this great work of research made by a non Konkomba. The time has come for we the Konkomba ethnic group to come out and write our own history and stories to redeem our image that has been marred by some few people whose major intention is to tarnish the image of the Konkomba. I am proud to be a Konkomba! Long live Konkomba! Long live Kikpakpang! Long live Ghana our motherland.

ReplyDeleteKwekudee, admittedly you are Genius, the write up is classic, all issues you have raised are explicit. My father told me a lot about Konkomba history and influence of the Germans and the British. Your piece confirms and gave me insight of what my father told me. In my village (N-nalog, about 12,9 km away from Saboba) for instance, there are still remnants of the German settlements, and the elders of the village still have very rich stories of their influence on the Konkomba. The issue of the use of horses by the Dagombas is exactly the same as my father told me. In my father's version of it, the Konkombas were not engaged in war or comflict with the Dagombas but simply feared the horses. One other account of my father says that the Dagomba success was in a way empowered by the German influence as a result of the revolt against the Germans by the Konkombas. History scholars know the truth about the Konkomba marginalization by their so called enemies but no body is ready to speak the truth. I am a scientist, but after reading your work, it has really prompted me to get the stories of these old illiterates documented less they die with it. Better still, you could still visit these people and you will be fascinated with their rich stories.

ReplyDeleteYour piece has also helped me estimate the age of my father. He told me he was born three months before the the Cow War(Sagbeli war). I commend you. God bless you

What again. I study this history in my final year, History of Northern Ghana. A book written by Cliff confirms this account. In fact, a certain white man also gave this, is it David, who received a posthumous award for that piece about Konkomba history. You are that historian that we need to reconstruct that history of Konkombas.

ReplyDeletePlease, some of the pictures appeared current tagged against scenes that date back. Did I see someone wearing Ghana @50 t-shirt?

Awesome

Very impressive. Kudos

ReplyDeleteWow! I'm touched. More of these will help educate our younger ones to appreciate how far we have come.