SERETSE KHAMA; THE BOTSWANA CHIEF WHO WAS FORCED BY THE BRITISH TO GIVE UP HIS THRONE FOR FIVE YEARS FOR MARRYING A WHITE WOMAN

"Sometimes the heart has its reasons

That reason itself just can't fathom."`Seretse Khama and Ruth

Bamangwato Tribal Chief Seretse Khama with his white Wife Ruth at the Tribal Capital of Bechuanaland

by Margaret Bourke-White

Before Joe Appiah and Peggy Cripps love odyssey there was Seretse Khama and Ruth Williams and Britain's King Edward VIII wasn't the only 20th century royal to give up his throne for love. In 1948, Seretse Khama, chief of the Ngwato or Bamangwato people, created a tremendous controversy by marrying a British woman, Ruth Williams. Despite pressure from his own people and the governments of Great Britain and South Africa, Khama refused to divorce his wife. He was the first high profile African to be involved in interracial marriage. Their marriage inspired the film "A Marriage of Inconvenience" starring Michael Duffield, Niamh Cusack, Raymond Johnson. The film is an adaptation of Michael Dutfield`s 1990 book on the Khamas, "A Marriage of Inconvenience, The Persecution of Ruth and Seretse Khama." There is also "A piece by Susan Williams, author of Colour Bar: The Triumph of Seretse Khama and His Nation."

1949 Khama Seretse King - Queen Ruth - Africa Press Photo

The British government exiled the couple to England in 1950. Only after Khama agreed to renounce his chiefdom in 1956 were they allowed to return to Bechuanaland, where Seretse Khama founded the Democratic Party. In 1966, the country gained its independence from Great Britain and became the Republic of Botswana, with Seretse Khama as its first prime minister. He was knighted by Queen Elizabeth II that year. From 1966 to his death in 1980, he served as the country's first president.

He was succeeded by Vice President Quett Masire. Forty thousand people paid their respects while his body lay in state in Gaborone. He was buried in the Khama family graveyard on a hill in Serowe, Central District.

President Ian Khama of Botswana, son of Seretse Khama and Ruth Williams

The "Unfortunate Marriage" of Seretse Khama

by Clare Rider, IT Archivist 1998-2009

'A difficult problem, to which some prominence has been given in the Press recently, has arisen from the marriage to an English girl of Seretse Khama, the Chief Designate of the Bamangwato Tribe in the Bechuanaland Protectorate.' So begins the initial memorandum to the British Cabinet on the subject of the Bamangwato chieftainship by Patrick Gordon Walker, Secretary of State for Commonwealth Relations, dated 19th July 1949.

It was to be the first of many such memoranda, since the marriage of a black African Chief to a white English girl in London was to cause a diplomatic storm in the British Commonwealth which was to last almost a decade. In a year that has witnessed the death of Lady Khama, as Ruth Williams was to become, it is appropriate to re-tell the story of her romance with the late Seretse Khama, a member of the Inner Temple, and the 'difficult problem' to which it gave rise.

It was while he was in London, living near Marble Arch and studying for his bar examinations that Seretse met Ruth Williams, a clerk in the claims department of Lloyd's underwriters, Cuthbert Heath. Born in Blackheath, south London, the daughter of a retired Indian army officer, she had served in the Women's Auxiliary Air Force during the Second World War, and was apparently 'an independent-minded girl in her early twenties' when she met Seretse at a London Missionary Society dance.

Although their initial meeting was not a success, their shared enthusiasm for jazz resulted in a blossoming romance and in September 1948 Seretse sent an air-mail letter to his uncle, Tshekedi, announcing that he planned to marry Ruth on 2nd October.

Tshekedi Khama, uncle of Seretse Khama, (in Bechuanaland), Chief of the Bamangwato who caused a scandal by marrying Englishwoman Ruth Williams. Original Publication: Picture Post - 5024 - Rights And Wrongs Of Seretse Khama - unpub. (Photo by Bert Hardy/Getty Images). Circa 29 Apr 1950

When Tshekedi expressed his outrage at the proposal and pressed the London Missionary Society to intervene to prevent the marriage, Seretse defied him and brought the planned wedding date forward to 24th September. However, the Vicar of St. George's, Campden Hill, who had agreed to conduct the marriage ceremony, lost his nerve in the face of mounting opposition and referred them to the Bishop of London, who was officiating at an ordination ceremony at St. Mary Abbot's, Kensington. The couple sat through the ordination service only to be told that the Bishop was not prepared to allow the marriage to take place in church without the approval of the British government. Both knew that this was unlikely to be forthcoming. Meanwhile Ruth had become estranged from her father, who thoroughly disapproved of the relationship, and was informed by her employers that, in the event of her marriage, she must choose between a transfer to their New York office or redundancy. Nevertheless, on 29th September 1948, in the face of all opposition, Seretse Khama married Ruth Williams at Kensington Registry Office.

Ruth Khama (1923 - 2002), the British-born wife of Bamangwato tribal chief Seretse Khama, watching as Serowe women bear gifts of food in containers on their heads to sustain her while her husband is in England defending his right to remain as head of his country. (Photo by Margaret Bourke-White//Time Life Pictures/Getty Images). Circa 01 Apr 1950

The diplomatic storm was just beginning. Seretse was summoned back to Bechuanaland by Tshedeki, arriving there on 22nd October 1948, and faced a four day grilling at the full tribal assembly or kgotla, from 15th to 19th November, for breaking tribal custom and disregarding the regent's command. 'The tribe at this first meeting, with almost one voice, condemned the marriage and resolved that all steps should be taken to prevent Seretse's white wife from entering the Bamangwato Reserve'.

However, Seretse was adamant that he would not return to the Reserve without his wife, and suspicions began to arise among the people that Tshedeki was aiming to banish Seretse and to claim the Chieftainship for himself. Therefore at a second meeting of the kgotla in December, a significant number of tribesmen withdrew their objection to the marriage and demanded a guarantee that Seretse would be allowed to return freely to his tribal lands if he went back to England to pursue his legal studies. When Seretse did return from London to the Protectorate in June 1949 and made it clear that he would leave permanently if his wife were not allowed to join him, a third kgotla meeting agreed to accept him as their Chief on any terms and, on 20th August, Ruth Khama arrived at Serowe. In this unexpected turn of events, Tshekedi found his authority overthrown by the vast majority of the tribe which he had ruled with a firm hand for over twenty years.

However, Seretse was adamant that he would not return to the Reserve without his wife, and suspicions began to arise among the people that Tshedeki was aiming to banish Seretse and to claim the Chieftainship for himself. Therefore at a second meeting of the kgotla in December, a significant number of tribesmen withdrew their objection to the marriage and demanded a guarantee that Seretse would be allowed to return freely to his tribal lands if he went back to England to pursue his legal studies. When Seretse did return from London to the Protectorate in June 1949 and made it clear that he would leave permanently if his wife were not allowed to join him, a third kgotla meeting agreed to accept him as their Chief on any terms and, on 20th August, Ruth Khama arrived at Serowe. In this unexpected turn of events, Tshekedi found his authority overthrown by the vast majority of the tribe which he had ruled with a firm hand for over twenty years.

In a bid to regain support, he threatened to leave his people and settle in voluntary exile in the Bakwena Reserve. His bluff called, Tshekedi left his homeland unopposed, accompanied by a small band of loyal followers. However, Seretse's future as Chief was far from secure. The British government had not yet recognised him and, at the end of October 1949, the Union of South Africa declared him and his wife as prohibited immigrants.

If they set foot in Mafeking, the headquarters of the Bechuanaland Protectorate, which was situated over the border in South Africa, they would be arrested. How could Serestse effectively rule his people, if he could not negotiate with his powerful neighbours, South Africa and Southern Rhodesia, who both refused to recognize his authority, and could not even enter the headquarters of his own British Protectorate ?

If they set foot in Mafeking, the headquarters of the Bechuanaland Protectorate, which was situated over the border in South Africa, they would be arrested. How could Serestse effectively rule his people, if he could not negotiate with his powerful neighbours, South Africa and Southern Rhodesia, who both refused to recognize his authority, and could not even enter the headquarters of his own British Protectorate ?

Bamangwato Royal Family member Seretse Khama (C) leaves London with his family which includes British-born wife Ruth (1923 - 2002) and son Seretse Ian Khama, also seen is friend Clement Freud. (Photo by Brian Seed//Time Life Pictures/Getty Images)

From the outset, the white governments of the Union of South Africa and Southern Rhodesian had expressed grave concerns about the marriage and the consequences of British recognition of Seretse as Chief. Indeed, the Prime Minister of Southern Rhodesia warned the British High Commissioner, Sir Evelyn Baring, that the more extreme nationalists would not be willing to remain associated with a country which officially recognised an African Chief married to a white woman, 'and that they would make Seretse's recognition the occasion of an appeal to the country for the establishment of a Republic; and not only a Republic, but of a Republic outside the Commonwealth' . The Prime Minister of the Union of South Africa confirmed that he would not oppose such a move, whilst keeping a watchful eye on the situation in Bechuanaland. Under the provisions of the South Africa Act of 1909, the Union laid claim to the neighbouring tribal territories and, as the Secretary of State for Commonwealth Relations pointed out to the Cabinet in 1949, the 'demand for this transfer might become more insistent if we disregard the Union government's views'. He went on, 'indeed, we cannot exclude the possibility of an armed incursion into the Bechuanaland Protectorate from the Union if Serestse were to be recognised forthwith, while feeling on the subject is inflamed'.

UK London group portrait Ruth Seretse Khama their children Jacqueline and Ian Khama was about to leave for Botswana. 1956

Was the Secretary of State overreacting? Probably not when one considers that the Prime Minister of South Africa, Dr. D. F. Malan, had led the National Party to its first victory in 1948 specifically on a platform of apartheid. The British government was in a dilemma. Should it summon Seretse to London 'so that an attempt might be made to persuade him to relinquish voluntarily his claim to the chieftainship?' At a Cabinet meeting on 21st July 1949 the Secretary of State for the Colonies violently disagreed. He saw that the government would be widely criticised for attempting to influence Seretse in this way to pander to white opinion in South Africa and pointed out the danger of appearing to be racist. The Cabinet agreed. 'The issue was not one of the merits of demerits of mixed marriages and the Government should vigorously rebut any suggestion that their attitude to this question was in any way determined by purely racial considerations'. Their prime object must be to safeguard the future well-being of the Bamangwato themselves. A judicial enquiry would give everyone time for reflection and for tempers to cool. Accordingly an enquiry was arranged in Bechuanaland to examine the suitability of Seretse Khama for the Chieftainship of the Bamangwato Tribe. It reported in December 1949.

The outcome of the enquiry was not entirely predictable. For example, it concluded that if the tribe had forgiven Serestse for failing to follow native custom over his marriage, 'who are we to insist on his punishment ?' That particular issue was closed and did not in itself render Seretse unfitted to rule. Also, 'though a typical African in build and features', the enquirers found Seretse an intelligent, well-spoken, educated man 'who has assimilated, to a great extent, the manners and thoughts of an Oxford undergraduate'.

However, the results of the marriage in souring relations with neighbouring Commonwealth countries could not be ignored. Since, in their opinion, friendly and co-operative relations with South Africa and Rhodesia were essential to the well-being of the Bamangwato Tribe and the whole of the Protectorate, Seretse, who enjoyed neither, could not be deemed fit to rule. They concluded: 'We have no hesitation in finding that, but for his unfortunate marriage, his prospects as Chief are as bright as those of any native in Africa with whom we have come into contact'.

Seretse could not be recognised as Chief and was recalled to London in 1950. He cabled his wife from the British capital, 'Tribe and myself tricked by British Government. Am banned from whole protectorate. Love Seretse'. Ruth remained in Bechuanaland for a while afterwards, and Serestse was permitted to join her there for the birth of their first child. They both returned to London and Ruth became reconciled to her father.

In 1952 Seretse was excluded permanently from the Chieftainship and was required to live outside his native country. Ironically, Serestse's uncle Tshekedi, who was still living in the Bakwena Reserve, was also banned from the Bamangwato reserve, whilst the British arranged for a caretaker government, incorporating a Native Authority. It must have seemed to Seretse that he would never return to his native land.

In 1952 Seretse was excluded permanently from the Chieftainship and was required to live outside his native country. Ironically, Serestse's uncle Tshekedi, who was still living in the Bakwena Reserve, was also banned from the Bamangwato reserve, whilst the British arranged for a caretaker government, incorporating a Native Authority. It must have seemed to Seretse that he would never return to his native land.

However, his cause was not forgotten either in London or in Africa, and a number of politicians kept the issue alive in the British Parliament, including Winston Churchill and Anthony Wedgwood Benn. In 1956 the Bamangwato cabled the Queen to ask for the return of their Chief, and after both Seretse and Tshekedi had signed undertakings renouncing the Chieftainship for themselves and their heirs and agreeing to live in harmony with each other, they were allowed to return home as private citizens.

After a few years living as a cattle rancher and dabbling in local politics, Seretse was motivated to enter national politics. He founded the Bechuanaland Democratic Party, which won the 1965 elections, the prelude to his country's gaining independence as Botswana in 1966. He was knighted that year and became Botswana's first president, serving a total of four presidential terms before his untimely death in 1980 at the age of 59. He left Botswana an increasingly democratic and prosperous country with a significant role in the politics of Southern Africa. He remained a popular figure in his native country, and is remembered by G J Phipps Jones, Headmaster of Moeding College in Botswana during Seretse's presidency who has since returned to Britain, as 'very caring and considerate…a softly spoken, gentle man.' Ruth, a keen charity worker, continued live in Botswana and to undertake a wide range of charitable duties, including acting as president of the Botswana Red Cross.

Known to the population as 'Lady K', she was a familiar figure in her adopted country, considering herself a Motswana, or native citizen of Botswana, until her death on 22 May 2002. She is survived by their daughter and three sons, one of whom, Ian, is now Vice-President of Botswana.

The story of Seretse and Ruth is one that should not be forgotten. It has many of the elements of a Shakespearean drama or Disney feature film with star-crossed lovers, ambitious uncle, hypocritical advisors, powerful enemies and, above all, a happy ending. However, government papers and contemporary accounts of their treatment at the hands of the British government do not make comfortable reading.

Short Biography of Seretse Khama

Sir Seretse Khama, KBE ( July 1, 1921 – July 13, 1980) was a statesman from Botswana. Born into one of the more powerful of the royal families of what was then the British Protectorate of Bechuanaland, and educated abroad in neighbouring South Africa and in the United Kingdom, he returned home—with a popular but controversial bride—to lead his country's independence movement. He founded the Botswana Democratic Party in 1962 and became Prime Minister in 1965. In 1966, Botswana gained independence and Khama became its first president. During his presidency, the country underwent rapid economic and social progress.

Childhood and education

Seretse Khama was born in 1921 in Serowe, in what was then the Bechuanaland Protectorate. He was the son of Sekgoma Khama II, the paramount chief of the Bamangwato people, and the grandson of Khama III, their king. The name "Seretse" means “the clay that binds", and was given to him to celebrate the recent reconciliation of his father and grandfather; this reconciliation assured Seretse’s own ascension to the throne with his aged father’s death in 1925. At the age of four, Seretse became kgosi (king), with his uncle Tshekedi Khama as his regent and guardian.

After spending most of his youth in South African boarding schools, Khama attended Fort Hare University College there, graduating with a general B.A. in 1944. He then travelled to the United Kingdom and spent a year at Balliol College, Oxford, before joining the Inner Temple in London in 1946, to study to become a barrister.

Bamangwato tribal chief Seretse Khama (R) standing before Kgotla tribal council meeting explaining why he has to go to London to defend himself in front of British Commonwealth officials because of his mix marriage.

Marriage and exile

In June 1947, Khama met Ruth Williams, an English clerk at Lloyd's of London, and after a year of courtship, married her. The interracial marriage sparked a furore among both the apartheid government of South Africa and the tribal elders of the Bamangwato. On being informed of the marriage, Khama's uncle Tshekedi Khama demanded his return to Bechuanaland and the annulment of the marriage.

Seretse Khama and Ruth in Botswana

Khama did return to Serowe but after a series of kgotlas (public meetings), was re-affirmed by the elders in his role as the kgosi in 1949. Ruth Williams Khama, travelling with her new husband, proved similarly popular. Admitting defeat, Tshekedi Khama left Bechuanaland, while Khama returned to London to complete his studies.

However, the international ramifications of his marriage would not be so easily resolved. Having banned interracial marriage under the apartheid system, South Africa could not afford to have an interracial couple ruling just across their northern border.

Chief Seretse Khama speaking to tribsmen after return from exile. (Photo by Terrence Spencer//Time Life Pictures/Getty Images). 01 Oct 1956

As Bechuanaland was then a British protectorate (not a colony), the South African government immediately exerted pressure to have Khama removed from his chieftainship. Britain’s Labour government, then heavily in debt from World War II, could not afford to lose cheap South African gold and uranium supplies.

There was also a fear that South Africa might take more direct action against Bechuanaland, through economic sanctions or a military incursion. The British government therefore launched a parliamentary enquiry into Khama’s fitness for the chieftainship. Though the investigation reported that he was in fact eminently fit to rule Bechuanaland, "but for his unfortunate marriage", the government ordered the report suppressed (it would remain so for thirty years), and exiled Khama and his wife from Bechuanaland in 1951.

Return to politics

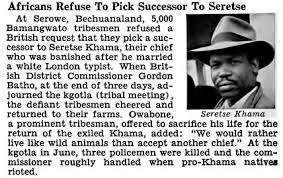

The sentence would not last nearly so long. Various groups protested against the government decision, holding it up as evidence of British racism. In Britain itself there was wide anger at the decision and calls for the resignation of Lord Salisbury, the minister responsible. A deputation of six Bamangwato travelled to London to see the exiled Khama and Lord Salisbury, in an echo of the 1895 deputation of three Bamangwato kgosis to Queen Victoria, but with no success. However, when ordered by the British High Commission to replace Khama, the people refused to do so.

In 1956, Seretse and Ruth Khama were allowed to return to Bechuanaland as private citizens, after he had renounced the tribal throne. Khama began an unsuccessful stint as a cattle rancher and dabbled in local politics, being elected to the tribal council in 1957. In 1960 he was diagnosed with diabetes.

In 1961, however, Khama leapt back onto the political scene by founding the nationalist Bechuanaland Democratic Party. His exile gave him an increased credibility with an independence-minded electorate, and the BDP swept aside its Socialist and Pan-Africanist rivals to dominate the 1965 elections. Now Prime Minister of Bechuanaland, Khama continued to push for Botswana's independence, from the newly-established capital of Gaborone. A 1965 constitution delineated a new Botswana government, and on 30 September 1966, Botswana gained its independence, with Khama acting as its first President. In 1966 Elizabeth II appointed Khama Knight Commander of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire'.

Presidency

At the time of its independence, Botswana was among the world’s poorest countries, even poorer than most other African countries. Khama set out on a vigorous economic programme intended to transform it into an export-based economy, built around beef, copper and diamonds. The 1967 discovery of Orapa’s diamond deposits aided this programme. However, other African countries have had abundant resources and still proved poor.

Between 1966 and 1980 Botswana had the fastest growing economy in the world. Much of this money was reinvested into infrastructure, health, and education costs, resulting in further economic development. Khama also instituted strong measures against corruption, the bane of so many other newly-independent African nations. Unlike other countries in Africa, his administration adopted market-friendly policies to foster economic development. Khama promised low and stable taxes to mining companies, liberalized trade, and increased personal freedoms. He maintained low marginal income tax rates to deter tax evasion and corruption. He upheld liberal democracy and non-racialism in the midst of a region embroiled in civil war, racial enmity and corruption.

On the foreign policy front, Khama exercised careful politics and did not allow militant groups to operate from within Botswana. According to Richard Dale "The Khama government had authority to do so by virtue of the 1963 Prevention of Violence Abroad act, and a week after independence, Sir Seretse Khama announced before the National Assembly his government’s policy to insure that Botswana would not become a base of operations for attacking any neighbor." Shortly before his death, Khama would play a major role in negotiating the end of the Rhodesian civil war and the resulting creation and independence of Zimbabwe.

On a personal level, he was known for his intelligence, integrity and sense of humour.

Legacy

Khama remained president until his death from pancreatic cancer in 1980, when he was succeeded by Vice President Quett Masire. Forty thousand people paid their respects while his body lay in state in Gaborone. He was buried in the Khama family graveyard on a hill in Serowe, Central District.

Botswanan`s President Ian Khama,son of Seretse Khama,the first president of Botswana

Twenty-eight years after Khama's death, his son Ian succeeded Festus Mogae as the fourth President of Botswana; in the 2009 general election he won a landslide victory in which a younger son, Tshekedi Khama, was elected as a parliamentarian from Serowe North West.

Tshekedi Khaman II Botswana's minster for Environment, Wildlife and Tourism, son of first president Seretse Khama

Source:http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Seretse_Khama)

Short biography on Ruth Williams Khama

Ruth Williams Khama, Lady Khama (9 December 1923 – 22 May 2002) was the wife of Botswana's first president Sir Seretse Khama, the Paramount Chief of its Bamangwato tribe. She served as the inaugural First Lady of Botswana from 1966 to 1980.

The marriage of a young, middle-class Englishwoman to a handsome black African would have caused comment and some unpleasant racial reactions in the England of 1948, but little more - except that, in this case, the young African was Seretse Khama, chief-in-waiting of the powerful Bamangwato tribe in the British colony of Bechuanaland. He was later to become first president of the independent state of Botswana.

Despite the description of the relationship by Julius Nyerere as a great love affair, its immediate result was tribal division and a political row involving Britain, South Africa and Southern Rhodesia, and eight years of official British hypocrisy.

Bamangwato tribal chief Seretse Khama w. his white British wife Ruth, on hill overlooking native huts in the tribal capital of Bechuanaland from which the British Commonwealth officials wish to remove him for marrying a white woman.

Born in Blackheath, south London, she was the daughter of a former Indian Army captain, then working in the tea trade. During the second world war, she left Eltham high school to join the Women's Auxiliary Air Force, serve as an ambulance driver and work at an emergency landing station at Beachy Head. When the war ended, she became a confidential clerk with a Lloyds underwriter. Her recreations were ice-skating, dancing and jazz.

Meanwhile, Seretse, after a year at Balliol College, Oxford, was studying law at the Temple, and living in a hostel near Marble Arch. He met Ruth at a London Missionary Society dance. After a year's courting, they decided to marry and, in September 1948, Seretse wrote to tell his uncle, Tshekedi Khama, acting regent of the Bamangwato tribe; he said later that he had not asked for his uncle's consent because he knew it would be refused.

In Bechuanaland, the chief's wife was traditionally regarded as the mother of the tribe, and Tshekedi could not envisage a white woman in the role. Through the British high commissioner and the Colonial Office, he tried to prevent the marriage. Then the parson who had reluctantly agreed to marry the couple lost his nerve, and referred their request to the Bishop of London, Dr John Wand. He, in turn, was under pressure from the British government, and told them they could only marry if the government agreed.

Seretse and Ruth advanced their wedding date from October, and were married in a register office. Ruth was sacked from her job, and her father turned her out of the house. Seretse returned alone to Bechuanaland.

Tshekedi now called a kgotla, or tribal general council, at which 14 of the 15 most important royal blood relatives opposed the marriage. So Seretse returned to London to continue his law studies and, six months later, the colonial administration confirmed the rejection by the kgotla of Ruth as tribal queen.

Meanwhile, the suspicion was fomented that Tshekedi wanted the chieftainship for himself, driving a further wedge between uncle and nephew. Seretse now ret- urned to Bechuanaland to face 4,000 people at a second kgotla. Tshekedi addressed the meeting first: he said he would hand over the leadership to Seretse, but "if he brings his white wife here, I will fight him to the death". He asked those who supported him to stand; only nine did so.

After Seretse himself had spoken, 43 people stood up to indicate their opposition to him. Sensing that opinion was moving in his favour, he then asked those who supported him to stand, and the whole meeting rose with shouts of "pula" (rain). This vote of approval might have ended the affair: Ruth was now in Bechuanaland, and pregnant, but at this point southern Africa's white racists became involved.

There was a furious regional reaction to claims of miscegenation. Sir Godfrey Huggins, then prime minister of Southern Rhodesia, told a cheering assembly that he had written to the high commissioner of Bechuanaland, Basutoland and Swaziland saying it would be "disastrous" if this "fellow" [Seretse] became chief of the Bamangwato.

The new South African prime minister Dr DF Malan, who had led the National party to its first victory in 1948 specifically on an apartheid platform, cabled the British government urging it to oppose the marriage, which he described as "nauseating". Philip Noel-Baker, the Labour government's secretary of state for Commonwealth relations, invited Seretse to discuss the future administration of the tribe.

He then gave a press conference, accusing the Labour government of double-crossing him. Patrick Gordon Walker, the new Commonwealth relations secretary - who denied any pressures from South Africa - tried unsuccessfully to rebut the accusation, only to be reproached by the then Conservative opposition leader Winston Churchill, who said that it had been "a very disreputable transaction".

Ruth (L), the British white wife of Bamangwato tribal chief Seretse Khama, listening as tribal women who have come with gifts, sing "Our Queen will come with rain" as they squat inside her sleeping porch during a thunderstorm.

In South Africa, the nationalist newspaper Die Transvaaler crowed: "While trying to prop up with words the whitewashed façade of lib- eralism, the British government has had, in practice, to concede the demands of apartheid." In London, when the Conservatives returned to power in 1951, they extended Seretse's banishment indefinitely, saying his return would endanger peace and good government in Bechuanaland, where this decision was promptly met with riots.

Ruth (3R), the British white wife of Bamangwato tribal chief Seretse Khama, w. five of her tribal friends, listing to BBC radio news of her husband's to an account of the decision to banish her husband fr. his homeland because he married her.Circa 1950

Both the Labour and Conservative parties behaved dishonourably towards Seretse to appease white racism, something that the former Labour prime minister Clement Attlee was later to admit. At least, however, Seretse had been allowed to go home in 1950 for the birth of his first child, after which he brought Ruth to England. She, in turn, was reconciled with her father.

In 1956, after the Bamangwato had cabled the Queen in London to ask for their chief, Seretse was finally allowed home. He promptly disclaimed the chieftainship, founded the Bechuanaland democratic party and won the 1965 elections, the prelude to Botswana's independence in 1966. Knighted that year, he served four terms as president, during which Ruth acted as his consort with dignity, though she never learned the local languages.

After Seretse's death in 1980, she continued various charitable works - running women's clubs, acting as president of the Botswana Red Cross, and being involved with the girl guides. Ruth Williams Khama died of throat cancer at the age of 79. She and Seretse had a daughter and three sons, one of whom, Ian, is now vice-president of Botswana.

Source:http://www.guardian.co.uk/news/2002/may/29/guardianobituaries

SERETSE KHAMA STILL CONTROLS BOTSWANA FROM THE GRAVE

Khama (59), who has been president for four years and was vice-president for 10 years before that, has concentrated enormous power in his hands. One of his close relatives, Ramadeluka Seretse, is the minister in charge of the defence force, police, intelligence services and the law enforcement machinery.

So far, the president’s cronyism has escaped the attention of international corruption watchers. In terms of corruption, Botswana is ranked 32 out of 182 countries by Transparency International, the highest-placed nation in Africa. South Africa is way down the list, at 64.

For four decades the former British possession has been Africa’s golden boy with its high annual economic growth rates – gross domestic product growth in 2012 is projected to be 5.1% – and a reputation for good governance and political stability.

But this week the leader of Botswana’s political opposition, Dumelang Saleshando, accused Khama of “wanting to reduce Botswana to a “private entity”. He added: “His general attitude is that his associates in the Cabinet are indispensable.”

A Mail & Guardian investigation reveals that:

Khama has appointed many members of his family as well as friends to senior positions in the government and state agencies, sometimes to the detriment of good governance.

The most recent case was the appointment of his younger brother, Tshekedi, as minister of wildlife, environment and tourism last month. Tshekedi is a low-profile MP who has not distinguished himself in Parliament and it is unclear what qualifications he has for the job.

“He is a poor performer and has not brought a single motion to Parliament, although that was his role as a backbencher,” Saleshando said.

There are suspicions that, in some cases, the advancement of members of his circle aims to protect Khama’s own interests, specifically in the tourism sector. Throughout his presidency and much of his deputy presidency, the tourism minister has been a member of his inner circle.

Wilderness Holdings spokesperson Julia Swanepoel has confirmed that the president owns a 5% stake in Linyanti Investments, a subsidiary of JSE-listed Wilderness Holdings, which drew international flak for illegally occupying the ancestral land of the Bushmen in the Central Kalahari Game Reserve.

Linyanti owns the Linyanti Concession, which covers 1250km2 of the northern Kalahari in the Chobe district. Wilderness said last year that Khama had bought the shares “at a market-related price” in October 2002, when he was vice-president.

The M&G has also established that Khama’s nephew, Marcus Patrick Khama ter Haar, and his personal lawyer, Parks Baedzi Tafa, were both appointed directors of Wilderness Holdings in January last year.

Parks said he was a Wilderness director and that he was invited to serve on the board in his personal capacity as an attorney. But neither he nor Marcus had shares in Wilderness Holdings. “It is quite a large board and my service there has nothing to do with Khama,” Tafa said.

Marcus had not responded by the time of going to print.

One of the sources of jobs for pals is the strategic diamond industry, particularly De Beers Botswana and Debswana, the 50-50 joint venture between De Beers and the government. CIC Energy, a major coal-mining venture in Mmamabula that was recently taken over by the Indian conglomerate Jindal Steel and Power, is also a source of top jobs.

Many of Khama’s relatives and friends have benefited from government tenders and other business, particularly contracts handed out by the Botswana Defence Force and the Botswana Police Service.

Reacting to complaints that his government regularly bypassed tender processes, he accused critics of being “frivolous”.

Beneficiaries include his brothers, twins Tshekedi and Anthony, who are middlemen acting on behalf of the defence force.

Former senior officers of the defence force, which Khama headed until 1998 and which remains an important prop of his power, are among the major beneficiaries of state appointments and contracts.

Corruption charges have been investigated and laid against a number of Khama’s associates, but they have never resulted in a conviction.

The Khamas

Khama’s twin brothers came under close scrutiny this year over allegations that companies they own landed big contracts from the defence force when he was its commander.

Former University of Botswana political scientist Kenneth Good claims in Diamonds, Dispossession and Democracy in Botswana, published in 2008, that the defence force bought equipment from Seleka Springs, a company of which Tshekedi and Anthony Khama were directors.

Good was declared an undesirable immigrant and deported in 2005 after writing an academic paper that criticised Botswana’s system of “automatic succession” to the presidency.

The Botswana Guardian reported in April this year that Seleka Springs used its influence in 1998 to prevail on the defence force to buy 45 Austrian Pandur tanks.

This was contrary to the recommendations in the confidential report of a team of defence experts, presented to then-president Festus Mogae by the former chairperson of the defence council, Lieutenant General Mompati Merafhe, in 2001. The experts were concerned that the Pandurs were inferior to, but far more expensive than, Piranha tanks from Switzerland.

As the unqualified agents of the defence force, Seleka Springs bought the Pandur tanks for 426-million pula (R469-million), P26-million more than the going price for the Piranhas.

It was alleged that the Pandurs were unable to traverse sand dunes and needed refuelling after shorter distances than their more robust Swiss counterparts. Tests also showed that the Austrian tank had an unreliable engine and was costlier to maintain. Khama was defence force commander when the deal was approved in 1998.

It is believed that Seleka Springs, which has now been deregistered, was awarded 33 of 35 multimillion-pula defence force tenders from 1998. Good also alleged that in 1997 the defence force bought vehicles, especially Land-Rovers, from Lobatse Delta, also under the directorship of the Khama twins.

Tshekedi refused to speak to the M&G and attempts to contact Anthony were unsuccessful.

Ramadeluka Seretse

Ramadeluka Seretse, Khama’s cousin, is Botswana’s minister of defence, justice and security, under which fall the police, the Directorate of Intelligence Services, the Directorate of Public Prosecutions, the attorney general and the Directorate on Corruption and Economic Crimes.

A former defence force brigadier general, Seretse was controversially acquitted on corruption charges relating to government contracts worth P1.1-million awarded to RFT Botswana, of which he was chairperson and his wife, Sandra Salome, and brother, Bathusi Seretse, were directors. During the trial, he resigned from the Cabinet, but was reappointed after being acquitted.

Seretse was charged with failing to disclose his interests to the president when his company won tenders from the police to supply ammunition, firearms, surveillance cameras and electronic security equipment.

He told Parliament there was no question of impropriety on his part and that he had taken steps to avoid corruption and minimise the risk of his personal business interests compromising his ability to carry out his ministerial duties independently.

He said he had declared his business interests to the president and that tenders were handled by the ministerial tender committee, on which he did not have a seat.

The director of the Directorate on Corruption and Economic Crimes is Rose Seretse, Seretse’s cousin by marriage. Seretse’s ministry also oversees it.

The Botswana media also revealed this year that Hot Bread Shop/Cosy Care, a company owned by Seretse’s wife, Sandra, was awarded a tender to supply bread to all defence force camps in Botswana between 1990 and 2000.

Ramadeluka Seretse told Parliament that Hot Bread was one of nine companies given defence force tenders during that period.

In an interview, he accused the devil of trying to use people to bring him down, adding that he was strong enough not to blame “confused” people.

He said he had not benefited from his relationship with Khama and had been the minister since 2004, before Khama became president. About his corruption case, he said: “I did nothing wrong and there was no absolute evidence, hence my acquittal.”

The Mokaila brothers

Kitso and Tefo Mokaila are the president’s childhood friends and army colleagues. Their father, Dingaan Mokaila, served as the first private secretary to president Seretse Khama, Ian’s father, in the 1970s.

A former defence force captain, Kitso was environment and tourism minister in Khama’s Cabinet until Tshekedi Khama took over and is now minister of minerals, energy and water affairs. Seen as a member of Khama’s inner circle, he is tipped as future vice-president.

Tefo, like his father, is a personal secretary at State House.

Attempts to contact Kitso were unsuccessful, but Tefo said that his younger brothers, including Kitso, grew up with Khama and had always been close to him. “Doing the same job as his father did at State House is a coincidence and has nothing to do with knowing Khama. I’ve never been Ian’s friend and my job here was never planned for,” he said.

He said Khama was no more than his boss and that his duty was “to serve him as His Excellency”.

Isaac Kgosi

Isaac Kgosi, who heads the Directorate of Intelligence Services, was a close associate of Khama during the president’s years as defence force commander.

Kgosi rose to the position of head of military intelligence and became Khama’s senior personal secretary when the latter was vice-president.

The directorate, set up in 2008 by Khama to detect and investigate threats to national security, remains one of the president’s key power bases.

Kgosi has served Khama in different capacities over time — once as his personal bodyguard. They remain close, both professionally and personally. He refused to speak to the M&G.

Sheila Khama

Sheila Khama is the president’s aunt by marriage. She divorced his uncle, Sekgoma Khama, but kept the Khama surname.

She is the former chief executive officer of De Beers Botswana, the country’s largest mining company. She is a non-executive director of De Beers Botswana and a number of other companies, including Debswana, De Beers Prospecting Botswana, the government’s Botswana Diamond Valuing Company, salt and soda ash mine Botswana Ash and the Gope Exploration Company.

She is now based in Ghana, where she is the director of extractive resources services of the African Centre for Economic Transformation, an economic policy institute that supports the long-term growth and transformation of African economies.

According to the company’s website, she holds a BA degree from the University of Botswana and an MBA from Edinburgh University’s business school. She could not be reached for comment.

Johan ter Haar

Khama’s friend, Johan ter Haar, was formerly married to Khama’s sister, Jacqueline. Until recently, he was chairperson of a parastatal, the Business and Economic Advisory Council, which was established in 2005 as an advisory body to assist the government in accelerating economic diversification and growth and reducing dependency on the mining sector.

He is now retired and lives in Belgium, where he could not be reached.

Dale ter Haar

Dale ter Haar is Ian Khama’s nephew, the son of Johan and Jacqueline. He is the general manager of CIC Energy, which, with local company Moepong Resources, is in charge of the Pula Mmabalula Energy Project, a giant planned coal-mining operation about 120km northeast of Gaborone.

The Sandton-based company was recently acquired by Jindal Steel & Power, one of India’s major steel producers, which has a significant presence in mining, power generation and infrastructure. With an annual revenue of more than $3.5-billion, Jindal is a part of a $15-billion diversified group.

Ter Haar, based in Gaborone, has been head of CIC Energy’s Botswana office since it was established in 2006. He was trained, like Khama, at the Sandhurst Royal Military Academy in Britain and served in the British army for 10 years, rising to the rank of major.

Ter Haar graduated in business administration from the University of Cardiff.

Approached for comment, he questioned the M&G’s “involvement” in Botswana’s affairs and said that being the president’s nephew did not benefit him because he had a good education and leadership skills.

Ter Haar said that he came back to Botswana in 2006 because CIC Energy was showing an interest in the coal-mining project. “I applied, went for an interview and got the job,” he said. “I am a capable man.”

Pelonomi Venson-Moitoi

Pelonomi Venson-Moitoi, the minister of education and skills development, hails from Serowe, Ian Khama’s home town, and is a close friend of the president and a member of his inner circle. She previously served as the minister of trade, industry, wildlife and tourism and the minister of communication, science and technology.

Although appointed tourism minister by Khama’s predecessor, Mogae, she allegedly landed the job on Khama’s recommendation.

As communications minister, she was in charge of the flow of information to the public through Botswana Television, Radio Botswana, RB2, Daily News and Kutlwano.

It is believed that Venson-Moitoi has easy access to Khama and the two are close confidants. She refused to answer the M&G’s questions, saying that “she has no time for people who don’t understand her capabilities”.

Tsetsele Fantan

Tsetsele Fantan, the daughter of Peto Sekgoma, the cousin of Sekgoma II, Seretse Khama’s father, is effectively Ian Khama’s cousin.

She is an important member of the tribunal of the Directorate of Intelligence Services, an appeals body with which all complaints against the directorate must be lodged. Khama personally appointed her to the position.

A former executive director of the African Comprehensive HIV/Aids Partnership, Fantan has worked for Debswana as a director of HIV/Aids management and as a personnel manager at Debswana’s Jwaneng mine.

She told the M&G that she did not need to defend herself because “many people know my capabilities. I have high-level jobs and, with time, have learned that silence is the best weapon because I’m a competent leader.”

Suggestions that she landed her Debswana position because of her relationship with Khama were designed to discredit the president, she said.

Fantan is on the board of the Botswana Building Society as an independent human resource consultant. The building society is part-owned by the Botswana government.

Thapelo Olopeng

Thapelo Olopeng, a former defence force captain, maintained his friendship with Khama after both men left the army. They have travelled together on Khama’s official trips abroad.

Now a businessperson, Olopeng’s latest venture is a newspaper called the Patriot, which he co-owns with defence force secretary general Mpho Balopi, Botswana Democratic Party (BDP) MP Guma Moyo and the chief executive of the Choppies supermarket chain, Ramachandran Ottapath. Mogae is chairperson of the group.

It is widely expected that the paper, set to be launched next month, will provide positive coverage of the Botswana Democratic Party-controlled government, although Olopeng denied this in an interview.

He also denied that the ruling party owned the paper and that he was Khama’s friend.

In 2009, Olopeng reportedly addressed a BDP rally in Gumare, in northwest Botswana.

George Tlhalerwa

Brigadier George Tlhalerwa last month became the latest senior member of the defence force to quit the army to work in the office of the president — as Khama’s senior private secretary.

The president’s a close ally, Khama appointed him commander of defence logistics in May this year.

Tlhalerwa refused to grant an interview and questioned the M&G’s interest in the politics of Botswana.

Guma Moyo

Moyo, a ruling-party parliamentarian and co-owner of the Patriot, was cleared on corruption charges in 2009 while assistant minister of finance and development planning.

Dropped from the executive after it emerged that he faced charges of corruption and a conflict of interest, he continued to serve as an MP.

Through his company, the Interest Research Bureau (IRB), he won tenders from the ministry of lands to collect debts in 2003 and then allegedly collected inflated charges from thousands of residential, commercial and industrial plot owners.

Moyo also allegedly bought a stake in a firm being pursued by the IRB for interest on land in Kasane. It was said that he misled the company into selling the land for P1-million after claiming that the office of the president had issued a directive that all plots in arrears had to be repossessed. The spokesperson for the attorney general, Abigail Hlabano, later said the state had decided not to prosecute him because of insufficient evidence.

Moyo refused to be interviewed.

Duke Masilo

Duke Masilo, a former defence force colonel, joined the civil service when Khama retired from the defence force in 1998 to become vice-president.

Masilo has been redeployed to the ministry of presidential affairs and public administration, where he is in charge of Khama’s flagship housing project. With Satar Dada and Paul Paledi, who are both in business, he is on the president’s housing appeal committee, which was set up to provide shelter for the needy.

Masilo told the M&G that the president had the right to choose with whom he wanted to work. Khama was always in the spotlight and under pressure and he needed the support of people he knew, he said.

“The good thing about us as his defence force employees is that he knows our strengths and weaknesses,” he said.

Satar Dada

Dada, the Botswana Democratic Party treasurer and at one time one of Khama’s appointed MPs, is widely seen as one of the president’s pillars of support and closest friends. But he denied this saying that they met only once a month at central committee meetings of the party.

Dada confirmed that the Toyota Motor Centre, which he owns, sells cars under contract to the government. Former transport minister Frank Ramsden told Parliament last year that between 2006 and 2011 the government spent P188.9-million on vehicles supplied by Dada.

Dada also supplied vehicles to the ruling party, enabling its candidates to campaign in the 2004 election.

Dada has a stake in the Associated Investment and Development Corporation, which, in turn, owns 40% of Ross Breeders, which dominates the day-old-chicken industry.

The corporation partly owns Nutrifeed/Master Feeds, which is said to control up to 95% of the feed market, and Dada also has a stake in the broiler market through Tswana Pride and Dikoko Tsa Botswana.

They own shares in Coldline, which dominates the import market and cold storage.

Dada said that government schools were among the clients of his chicken companies, but added: “We tender just like other companies — sometimes we succeed and sometimes we don’t.”

The official response

Approached for comment, government spokesperson Jeff Ramsay said Botswana was a very small country where “everybody knows everybody”.

He dismissed allegations of nepotism and cronyism made against President Ian Khama as “baseless and senseless” and said most governments employed officials who were related to their leaders. For example, Nelson Mandela had appointed his former wife, Winnie Madikizela-Mandela, as deputy arts minister and President Jacob Zuma’s ex-wife, Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma, served in his Cabinet.

Referring to Tshekedi Khama’s appointment as tourism minister, Ramsay said that the president did not need a minister to protect his interests.

“He has interests in tourism, but how will having a minister protect them? I find this whole issue sick,” he said.

Ramsay said Khama’s relatives who held government positions and did business with the state declared their interests. “Working for government is not a problem because the president knows how these individuals perform,” he said. — Yvonne Ditlhase (http://mg.co.za/article/2012-11-02-00-khama-inc-all-the-presidents-family-friends-and-close-colleagues)

Photo source:http://images.google.com/hosted/life/1f190fcdab6612fa.html

That reason itself just can't fathom."`Seretse Khama and Ruth

Bamangwato Tribal Chief Seretse Khama with his white Wife Ruth at the Tribal Capital of Bechuanaland

by Margaret Bourke-White

1949 Khama Seretse King - Queen Ruth - Africa Press Photo

The British government exiled the couple to England in 1950. Only after Khama agreed to renounce his chiefdom in 1956 were they allowed to return to Bechuanaland, where Seretse Khama founded the Democratic Party. In 1966, the country gained its independence from Great Britain and became the Republic of Botswana, with Seretse Khama as its first prime minister. He was knighted by Queen Elizabeth II that year. From 1966 to his death in 1980, he served as the country's first president.

Bamangwato Royal Family member Seretse Khama leaving London. (Photo by Brian Seed//Time Life Pictures/Getty Images)

He was succeeded by Vice President Quett Masire. Forty thousand people paid their respects while his body lay in state in Gaborone. He was buried in the Khama family graveyard on a hill in Serowe, Central District.

President Ian Khama of Botswana, son of Seretse Khama and Ruth Williams

Twenty-eight years after Khama's death, his son Ian succeeded Festus Mogae as the fourth President of Botswana; in the 2009 general election he won a landslide victory in which a younger son, Tshekedi Khama, was elected as a parliamentarian from Serowe North West.

The "Unfortunate Marriage" of Seretse Khama

by Clare Rider, IT Archivist 1998-2009

'A difficult problem, to which some prominence has been given in the Press recently, has arisen from the marriage to an English girl of Seretse Khama, the Chief Designate of the Bamangwato Tribe in the Bechuanaland Protectorate.' So begins the initial memorandum to the British Cabinet on the subject of the Bamangwato chieftainship by Patrick Gordon Walker, Secretary of State for Commonwealth Relations, dated 19th July 1949.

Seretse Khama, chief of the Bamangwato of Bechuanaland, 29th April 1950. Exiled in 1951, Khama returned in 1956 and in 1966 became the first president of the newly independent Botswana. 29th April 1950. Original Publication : Picture Post - 5024 - Rights And Wrongs Of Seretse Khama - pub. 1950 (Photo by Bert Hardy/Picture Post/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

It was to be the first of many such memoranda, since the marriage of a black African Chief to a white English girl in London was to cause a diplomatic storm in the British Commonwealth which was to last almost a decade. In a year that has witnessed the death of Lady Khama, as Ruth Williams was to become, it is appropriate to re-tell the story of her romance with the late Seretse Khama, a member of the Inner Temple, and the 'difficult problem' to which it gave rise.

Seretse Khama and Family:The African politician Seretse Khama (1921-1980) at home in Surrey with his wife Ruth, and their daugher Jacqueline and baby son Seretse, 1953

Seretse Khama was born on 1st July 1921, the son of Sekgoma, Chief of the Bamangwato (or Bangwato) Tribe and ruler of the Bamangwato Reserve in the British Protectorate of Bechuanaland, now known as Botswana. The Bamangwato Reserve, which had been established in 1899 in the time of Seretse's grandfather, Khama III, comprised an area of approximately 40,000 square miles in Southern Africa. In 1946 it had an African population of about 10,000 (divided into several tribes including the Bangwato) and a European population of around 500. When Sekgoma died in 1925, Seretse was still in infancy and a regency was established, with his uncle, Tshekedi Khama, assuming the roles of Seretse's guardian and Acting Chief of the Bamangwato Tribe. Tshekedi sent his ward to England to continue his education, studying law at Balliol College, Oxford, and then at the Inner Temple in London, to which he was admitted on 14th October 1946.

s)

April 1950: Bamangwato tribal chief Seretse Khama w. his white British wife Ruth, in his new Chevrolet, saying goodbye while his sister Oratile sadly looks in, on his way to the airport for a flight to London to answers to British Commonwealth officials. (Photo by Margaret Bourke-White/Time & Life Pictures/Getty Images)

It was while he was in London, living near Marble Arch and studying for his bar examinations that Seretse met Ruth Williams, a clerk in the claims department of Lloyd's underwriters, Cuthbert Heath. Born in Blackheath, south London, the daughter of a retired Indian army officer, she had served in the Women's Auxiliary Air Force during the Second World War, and was apparently 'an independent-minded girl in her early twenties' when she met Seretse at a London Missionary Society dance.

Ruth Khama, nee Williams, wife of the chief of the Bamangwato of Bechuanaland, Seretse Khama, 29th April 1950. Exiled in 1951, Khama returned in 1956 and in 1966 became the first president of the newly independent Botswana. Original Publication : Picture Post - 5024 - Rights And Wrongs Of Seretse Khama - pub. 1950 (Photo by Bert Hardy/Picture Post/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

Tshekedi Khama, uncle of Seretse Khama, (in Bechuanaland), Chief of the Bamangwato who caused a scandal by marrying Englishwoman Ruth Williams. Original Publication: Picture Post - 5024 - Rights And Wrongs Of Seretse Khama - unpub. (Photo by Bert Hardy/Getty Images). Circa 29 Apr 1950

When Tshekedi expressed his outrage at the proposal and pressed the London Missionary Society to intervene to prevent the marriage, Seretse defied him and brought the planned wedding date forward to 24th September. However, the Vicar of St. George's, Campden Hill, who had agreed to conduct the marriage ceremony, lost his nerve in the face of mounting opposition and referred them to the Bishop of London, who was officiating at an ordination ceremony at St. Mary Abbot's, Kensington. The couple sat through the ordination service only to be told that the Bishop was not prepared to allow the marriage to take place in church without the approval of the British government. Both knew that this was unlikely to be forthcoming. Meanwhile Ruth had become estranged from her father, who thoroughly disapproved of the relationship, and was informed by her employers that, in the event of her marriage, she must choose between a transfer to their New York office or redundancy. Nevertheless, on 29th September 1948, in the face of all opposition, Seretse Khama married Ruth Williams at Kensington Registry Office.

Ruth Khama (1923 - 2002), the British-born wife of Bamangwato tribal chief Seretse Khama, watching as Serowe women bear gifts of food in containers on their heads to sustain her while her husband is in England defending his right to remain as head of his country. (Photo by Margaret Bourke-White//Time Life Pictures/Getty Images). Circa 01 Apr 1950

The diplomatic storm was just beginning. Seretse was summoned back to Bechuanaland by Tshedeki, arriving there on 22nd October 1948, and faced a four day grilling at the full tribal assembly or kgotla, from 15th to 19th November, for breaking tribal custom and disregarding the regent's command. 'The tribe at this first meeting, with almost one voice, condemned the marriage and resolved that all steps should be taken to prevent Seretse's white wife from entering the Bamangwato Reserve'.

1956 Press Photo Seretse Khama Going Home

Bamangwato Royal Family member Seretse Khama (C) leaves London with his family which includes British-born wife Ruth (1923 - 2002) and son Seretse Ian Khama, also seen is friend Clement Freud. (Photo by Brian Seed//Time Life Pictures/Getty Images)

From the outset, the white governments of the Union of South Africa and Southern Rhodesian had expressed grave concerns about the marriage and the consequences of British recognition of Seretse as Chief. Indeed, the Prime Minister of Southern Rhodesia warned the British High Commissioner, Sir Evelyn Baring, that the more extreme nationalists would not be willing to remain associated with a country which officially recognised an African Chief married to a white woman, 'and that they would make Seretse's recognition the occasion of an appeal to the country for the establishment of a Republic; and not only a Republic, but of a Republic outside the Commonwealth' . The Prime Minister of the Union of South Africa confirmed that he would not oppose such a move, whilst keeping a watchful eye on the situation in Bechuanaland. Under the provisions of the South Africa Act of 1909, the Union laid claim to the neighbouring tribal territories and, as the Secretary of State for Commonwealth Relations pointed out to the Cabinet in 1949, the 'demand for this transfer might become more insistent if we disregard the Union government's views'. He went on, 'indeed, we cannot exclude the possibility of an armed incursion into the Bechuanaland Protectorate from the Union if Serestse were to be recognised forthwith, while feeling on the subject is inflamed'.

UK London group portrait Ruth Seretse Khama their children Jacqueline and Ian Khama was about to leave for Botswana. 1956

Was the Secretary of State overreacting? Probably not when one considers that the Prime Minister of South Africa, Dr. D. F. Malan, had led the National Party to its first victory in 1948 specifically on a platform of apartheid. The British government was in a dilemma. Should it summon Seretse to London 'so that an attempt might be made to persuade him to relinquish voluntarily his claim to the chieftainship?' At a Cabinet meeting on 21st July 1949 the Secretary of State for the Colonies violently disagreed. He saw that the government would be widely criticised for attempting to influence Seretse in this way to pander to white opinion in South Africa and pointed out the danger of appearing to be racist. The Cabinet agreed. 'The issue was not one of the merits of demerits of mixed marriages and the Government should vigorously rebut any suggestion that their attitude to this question was in any way determined by purely racial considerations'. Their prime object must be to safeguard the future well-being of the Bamangwato themselves. A judicial enquiry would give everyone time for reflection and for tempers to cool. Accordingly an enquiry was arranged in Bechuanaland to examine the suitability of Seretse Khama for the Chieftainship of the Bamangwato Tribe. It reported in December 1949.

The outcome of the enquiry was not entirely predictable. For example, it concluded that if the tribe had forgiven Serestse for failing to follow native custom over his marriage, 'who are we to insist on his punishment ?' That particular issue was closed and did not in itself render Seretse unfitted to rule. Also, 'though a typical African in build and features', the enquirers found Seretse an intelligent, well-spoken, educated man 'who has assimilated, to a great extent, the manners and thoughts of an Oxford undergraduate'.

However, the results of the marriage in souring relations with neighbouring Commonwealth countries could not be ignored. Since, in their opinion, friendly and co-operative relations with South Africa and Rhodesia were essential to the well-being of the Bamangwato Tribe and the whole of the Protectorate, Seretse, who enjoyed neither, could not be deemed fit to rule. They concluded: 'We have no hesitation in finding that, but for his unfortunate marriage, his prospects as Chief are as bright as those of any native in Africa with whom we have come into contact'.

Seretse could not be recognised as Chief and was recalled to London in 1950. He cabled his wife from the British capital, 'Tribe and myself tricked by British Government. Am banned from whole protectorate. Love Seretse'. Ruth remained in Bechuanaland for a while afterwards, and Serestse was permitted to join her there for the birth of their first child. They both returned to London and Ruth became reconciled to her father.

However, his cause was not forgotten either in London or in Africa, and a number of politicians kept the issue alive in the British Parliament, including Winston Churchill and Anthony Wedgwood Benn. In 1956 the Bamangwato cabled the Queen to ask for the return of their Chief, and after both Seretse and Tshekedi had signed undertakings renouncing the Chieftainship for themselves and their heirs and agreeing to live in harmony with each other, they were allowed to return home as private citizens.

After a few years living as a cattle rancher and dabbling in local politics, Seretse was motivated to enter national politics. He founded the Bechuanaland Democratic Party, which won the 1965 elections, the prelude to his country's gaining independence as Botswana in 1966. He was knighted that year and became Botswana's first president, serving a total of four presidential terms before his untimely death in 1980 at the age of 59. He left Botswana an increasingly democratic and prosperous country with a significant role in the politics of Southern Africa. He remained a popular figure in his native country, and is remembered by G J Phipps Jones, Headmaster of Moeding College in Botswana during Seretse's presidency who has since returned to Britain, as 'very caring and considerate…a softly spoken, gentle man.' Ruth, a keen charity worker, continued live in Botswana and to undertake a wide range of charitable duties, including acting as president of the Botswana Red Cross.

Seretse Khama and his wife Ruth aka "Lady K" serving meal

Known to the population as 'Lady K', she was a familiar figure in her adopted country, considering herself a Motswana, or native citizen of Botswana, until her death on 22 May 2002. She is survived by their daughter and three sons, one of whom, Ian, is now Vice-President of Botswana.

The story of Seretse and Ruth is one that should not be forgotten. It has many of the elements of a Shakespearean drama or Disney feature film with star-crossed lovers, ambitious uncle, hypocritical advisors, powerful enemies and, above all, a happy ending. However, government papers and contemporary accounts of their treatment at the hands of the British government do not make comfortable reading.

Seretse Khama

Short Biography of Seretse Khama

Sir Seretse Khama, KBE ( July 1, 1921 – July 13, 1980) was a statesman from Botswana. Born into one of the more powerful of the royal families of what was then the British Protectorate of Bechuanaland, and educated abroad in neighbouring South Africa and in the United Kingdom, he returned home—with a popular but controversial bride—to lead his country's independence movement. He founded the Botswana Democratic Party in 1962 and became Prime Minister in 1965. In 1966, Botswana gained independence and Khama became its first president. During his presidency, the country underwent rapid economic and social progress.

Sir Seretse Khama, KBE ( July 1, 1921 – July 13, 1980)

Childhood and education

Seretse Khama was born in 1921 in Serowe, in what was then the Bechuanaland Protectorate. He was the son of Sekgoma Khama II, the paramount chief of the Bamangwato people, and the grandson of Khama III, their king. The name "Seretse" means “the clay that binds", and was given to him to celebrate the recent reconciliation of his father and grandfather; this reconciliation assured Seretse’s own ascension to the throne with his aged father’s death in 1925. At the age of four, Seretse became kgosi (king), with his uncle Tshekedi Khama as his regent and guardian.

Seretse Khama (1921 - 1980), exiled kgosi (king) of the Bamangwato people of the Bechuanaland Protectorate (now Botswana), London, 16th March 1950. Khama is in dispute with his uncle Tshekedi Khama over his marriage to a white English woman, Ruth Williams. Tshekedi has tried to have the marriage annulled. On independence in 1966, Seretse Khama became first President of Botswana. (Photo by Keystone/FPG/Archive Photos/Getty Images)

After spending most of his youth in South African boarding schools, Khama attended Fort Hare University College there, graduating with a general B.A. in 1944. He then travelled to the United Kingdom and spent a year at Balliol College, Oxford, before joining the Inner Temple in London in 1946, to study to become a barrister.

Bamangwato tribal chief Seretse Khama (R) standing before Kgotla tribal council meeting explaining why he has to go to London to defend himself in front of British Commonwealth officials because of his mix marriage.

Marriage and exile

Seretse Khama and Ruth Williams

In June 1947, Khama met Ruth Williams, an English clerk at Lloyd's of London, and after a year of courtship, married her. The interracial marriage sparked a furore among both the apartheid government of South Africa and the tribal elders of the Bamangwato. On being informed of the marriage, Khama's uncle Tshekedi Khama demanded his return to Bechuanaland and the annulment of the marriage.

Seretse Khama and Ruth in Botswana

Khama did return to Serowe but after a series of kgotlas (public meetings), was re-affirmed by the elders in his role as the kgosi in 1949. Ruth Williams Khama, travelling with her new husband, proved similarly popular. Admitting defeat, Tshekedi Khama left Bechuanaland, while Khama returned to London to complete his studies.

However, the international ramifications of his marriage would not be so easily resolved. Having banned interracial marriage under the apartheid system, South Africa could not afford to have an interracial couple ruling just across their northern border.

Chief Seretse Khama speaking to tribsmen after return from exile. (Photo by Terrence Spencer//Time Life Pictures/Getty Images). 01 Oct 1956

As Bechuanaland was then a British protectorate (not a colony), the South African government immediately exerted pressure to have Khama removed from his chieftainship. Britain’s Labour government, then heavily in debt from World War II, could not afford to lose cheap South African gold and uranium supplies.

There was also a fear that South Africa might take more direct action against Bechuanaland, through economic sanctions or a military incursion. The British government therefore launched a parliamentary enquiry into Khama’s fitness for the chieftainship. Though the investigation reported that he was in fact eminently fit to rule Bechuanaland, "but for his unfortunate marriage", the government ordered the report suppressed (it would remain so for thirty years), and exiled Khama and his wife from Bechuanaland in 1951.

Return to politics

The sentence would not last nearly so long. Various groups protested against the government decision, holding it up as evidence of British racism. In Britain itself there was wide anger at the decision and calls for the resignation of Lord Salisbury, the minister responsible. A deputation of six Bamangwato travelled to London to see the exiled Khama and Lord Salisbury, in an echo of the 1895 deputation of three Bamangwato kgosis to Queen Victoria, but with no success. However, when ordered by the British High Commission to replace Khama, the people refused to do so.

Seretse Khama

In 1956, Seretse and Ruth Khama were allowed to return to Bechuanaland as private citizens, after he had renounced the tribal throne. Khama began an unsuccessful stint as a cattle rancher and dabbled in local politics, being elected to the tribal council in 1957. In 1960 he was diagnosed with diabetes.

In 1961, however, Khama leapt back onto the political scene by founding the nationalist Bechuanaland Democratic Party. His exile gave him an increased credibility with an independence-minded electorate, and the BDP swept aside its Socialist and Pan-Africanist rivals to dominate the 1965 elections. Now Prime Minister of Bechuanaland, Khama continued to push for Botswana's independence, from the newly-established capital of Gaborone. A 1965 constitution delineated a new Botswana government, and on 30 September 1966, Botswana gained its independence, with Khama acting as its first President. In 1966 Elizabeth II appointed Khama Knight Commander of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire'.

Presidency

At the time of its independence, Botswana was among the world’s poorest countries, even poorer than most other African countries. Khama set out on a vigorous economic programme intended to transform it into an export-based economy, built around beef, copper and diamonds. The 1967 discovery of Orapa’s diamond deposits aided this programme. However, other African countries have had abundant resources and still proved poor.

Statue of Khama outside the Botswana Parliament building

Between 1966 and 1980 Botswana had the fastest growing economy in the world. Much of this money was reinvested into infrastructure, health, and education costs, resulting in further economic development. Khama also instituted strong measures against corruption, the bane of so many other newly-independent African nations. Unlike other countries in Africa, his administration adopted market-friendly policies to foster economic development. Khama promised low and stable taxes to mining companies, liberalized trade, and increased personal freedoms. He maintained low marginal income tax rates to deter tax evasion and corruption. He upheld liberal democracy and non-racialism in the midst of a region embroiled in civil war, racial enmity and corruption.

On the foreign policy front, Khama exercised careful politics and did not allow militant groups to operate from within Botswana. According to Richard Dale "The Khama government had authority to do so by virtue of the 1963 Prevention of Violence Abroad act, and a week after independence, Sir Seretse Khama announced before the National Assembly his government’s policy to insure that Botswana would not become a base of operations for attacking any neighbor." Shortly before his death, Khama would play a major role in negotiating the end of the Rhodesian civil war and the resulting creation and independence of Zimbabwe.

On a personal level, he was known for his intelligence, integrity and sense of humour.

Legacy

Jacquelene Khama,daughter of Seretse Khama

Khama remained president until his death from pancreatic cancer in 1980, when he was succeeded by Vice President Quett Masire. Forty thousand people paid their respects while his body lay in state in Gaborone. He was buried in the Khama family graveyard on a hill in Serowe, Central District.

Botswanan`s President Ian Khama,son of Seretse Khama,the first president of Botswana

Twenty-eight years after Khama's death, his son Ian succeeded Festus Mogae as the fourth President of Botswana; in the 2009 general election he won a landslide victory in which a younger son, Tshekedi Khama, was elected as a parliamentarian from Serowe North West.

Tshekedi Khaman II Botswana's minster for Environment, Wildlife and Tourism, son of first president Seretse Khama

Source:http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Seretse_Khama)

Short biography on Ruth Williams Khama

Ruth Williams Khama, Lady Khama (9 December 1923 – 22 May 2002) was the wife of Botswana's first president Sir Seretse Khama, the Paramount Chief of its Bamangwato tribe. She served as the inaugural First Lady of Botswana from 1966 to 1980.

March 1950: Ruth Khama (1923 - 2002), the British wife of Bamangwato tribal chief Seretse Khama, pouring coffee as kitten sits inside table, at her home. (Photo by Margaret Bourke-White/Time & Life Pictures/Getty Images)

The marriage of a young, middle-class Englishwoman to a handsome black African would have caused comment and some unpleasant racial reactions in the England of 1948, but little more - except that, in this case, the young African was Seretse Khama, chief-in-waiting of the powerful Bamangwato tribe in the British colony of Bechuanaland. He was later to become first president of the independent state of Botswana.

Despite the description of the relationship by Julius Nyerere as a great love affair, its immediate result was tribal division and a political row involving Britain, South Africa and Southern Rhodesia, and eight years of official British hypocrisy.

Bamangwato tribal chief Seretse Khama w. his white British wife Ruth, on hill overlooking native huts in the tribal capital of Bechuanaland from which the British Commonwealth officials wish to remove him for marrying a white woman.

Born in Blackheath, south London, she was the daughter of a former Indian Army captain, then working in the tea trade. During the second world war, she left Eltham high school to join the Women's Auxiliary Air Force, serve as an ambulance driver and work at an emergency landing station at Beachy Head. When the war ended, she became a confidential clerk with a Lloyds underwriter. Her recreations were ice-skating, dancing and jazz.

Meanwhile, Seretse, after a year at Balliol College, Oxford, was studying law at the Temple, and living in a hostel near Marble Arch. He met Ruth at a London Missionary Society dance. After a year's courting, they decided to marry and, in September 1948, Seretse wrote to tell his uncle, Tshekedi Khama, acting regent of the Bamangwato tribe; he said later that he had not asked for his uncle's consent because he knew it would be refused.

Ruth, the British white wife of Bamangwato tribal chief Seretse Khama, with her only white friends Doris & Allan Bradshaw examining their photo proofs taken by Margaret Bourke-White, at her home.

In Bechuanaland, the chief's wife was traditionally regarded as the mother of the tribe, and Tshekedi could not envisage a white woman in the role. Through the British high commissioner and the Colonial Office, he tried to prevent the marriage. Then the parson who had reluctantly agreed to marry the couple lost his nerve, and referred their request to the Bishop of London, Dr John Wand. He, in turn, was under pressure from the British government, and told them they could only marry if the government agreed.