TOM MBOYA: THE CHARISMATIC PAN-AFRICANIST, FREEDOM FIGHTER AND THE GREATEST PRESIDENT KENYA NEVER HAD

“We will never, never sell our freedom for capital or technical aid. We stand for freedom at any cost.” -Tom Mboya on 8th December 1959 as he chaired the All Africa People’ s Conference

Thomas Joseph Odhiambo Mboya (15 August 1930 – 5 July 1969) affectionately called was a Kenyan leading charismatic anti-colonial figure, astute Pan-Africanist, formidable Trade Unionist and a brilliant statesman. He was a key ally of Mzee Jomo Kenyatta and the two leaders and other Kenyans fought against British imperialist rule in Kenya which culminated in an independence in 1963. In an eulogy at Mboya’s requiem mass, President Jomo Kenyatta said “Kenya’s independence would have been seriously compromised were it not for the courage and steadfastness of Tom Mboya.”

Without this great Kenyan Tom Mboya there would have probably been no first black US president Barack Obama nor Wangari Maathai, winner of the Nobel Peace Prize. In 1959 Mboya organized the Airlift Africa project, together with the African-American Students Foundation in the United States, through which 81 Kenyan students were flown to the U.S. to study at U.S. universities. In a Declassified CIA information in an undated issue of Ramparts, an American political and literary magazine published in the 1960s and early 1970s, shows how Tom Mboya asked for president Kennedy`s help to airlift Kenyan students to US for higher education. According to Kennedy: " ... 'Mr Mboya came to see us and asked for help, when none of the other foundations could give it, when the federal government had turned it down quite precisely. We felt something ought to be done.' "One of the first students airlifted to America was Barack Obama Sr., who married a white Kansas native woman." Tom Mboya`s wife Pamela Mboya and Dr Wangari Maathai were also beneciaries of Tom Mboya`s Airlift Africa project.

His intelligence and charm earned him worldwide recognition and respect; his performance at both national and continental level especially with Pan-Africanism was remarkable. At youthful age of 28 he was elected as the Chairman for the duration of the All-Africa People’s Conference convened by Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana in 1958. Tom Mboya was the most polished and most articulate spokesman of African nationalism to the rest of the world in the 1950s and 1960s.

He explained to the skeptical and the cynical in the West, that the dramatic events unfolding in colonial Kenya under the emergency, the Algerian war of independence, and the struggle against apartheid were one of a kind. Colonial oppression based on white supremacy had pushed Africans to a corner, he said. When African voices were silenced and racial oppression increased, any violent resistance, which arose, should be attributed to the oppressor not the oppressed. By and by the world came to rely on his clarity of thought in interpreting the new Africa. All this before he was thirty years old!

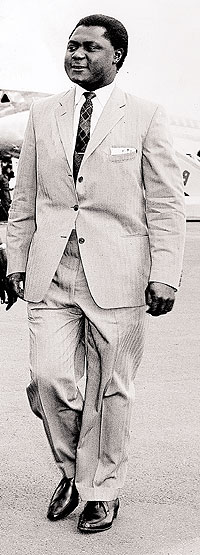

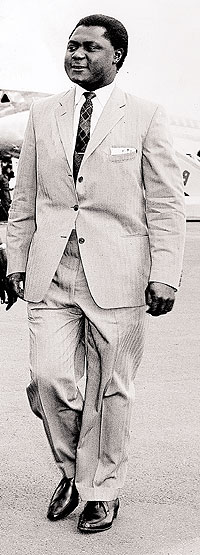

Tom Mboya and Mzee Jomo Kenyatta at state function

It was not only colonial brutality in Kenya that concerned him. When the Sharpeville Massacre of 1961 took place, Tom Mboya was among the first African leaders to call for the immediate expulsion of apartheid South Africa from the Commonwealth. He and other African leaders prevailed. South Africa was expelled from the Commonwealth that year.

Tom Mboya as a politician was the founder of the Nairobi People’s Congress Party in 1958. He was later instrumental in forming the Kenya African National Union (KANU) that formed the government upon independence, and became its first Secretary General. He may not have been too book smart, but he was intelligent and very hardworking leader. Despite being of ethnic Luo extraction, he was neither a Kenyan Luo nor an African politician, but a citizen of the world. He fought tribalism and tried to bring Kenyans together, a reason strong enough to have gotten him killed. “No African leader has an abler brain or a stronger will,” wrote one Englishwoman who knew Mboya during his lifetime.

Tom Mboya as a politician was the founder of the Nairobi People’s Congress Party in 1958. He was later instrumental in forming the Kenya African National Union (KANU) that formed the government upon independence, and became its first Secretary General. He may not have been too book smart, but he was intelligent and very hardworking leader. Despite being of ethnic Luo extraction, he was neither a Kenyan Luo nor an African politician, but a citizen of the world. He fought tribalism and tried to bring Kenyans together, a reason strong enough to have gotten him killed. “No African leader has an abler brain or a stronger will,” wrote one Englishwoman who knew Mboya during his lifetime.

Despite being one of the most prominent personalities in Kenyan history he died by an assassin’s bullet at the tender age of 39 on 5th July 1969. For when he was shot, the sound rang around the world. Radio stations in the US broke the news with shock and disbelief. He had just returned from a tour of the US. In the following morning, his assassination was front page news in The New York Times, The Times of London, Washington Post, Le Monde and the Times of India - to mention but a few. Television stations around the world extensively covered it. The British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) lead item in its international news that day was the following: “One of Africa’s youngest and most brilliant politicians, Mr Tom Mboya of Kenya has been assassinated.”

Mboya chats with Will Brandt future chancellor of Germany

His death was seen as one of the saddest moments in the history of post-independence Kenya and indeed of Africa. It is widely believed that his high profile and illustrious career as a brilliant and charismatic leader, led to his assassination. At the time of his assassination, he was the Minister of Economic Planning and Development. He is simply "a man Kenyan`s wanted to forget" as a result of his timely departure from this world but certainly not the world.

Tom Mboya was born on April 15, 1930 in Kilimanbogo on a Sisal Estate near Thika town in what was called the 'White Highlands' of Kenya . His father Leonardus Ndiege was a sisal cutter. His mother, Marcella Awour, named him Odhiambo, a Luo name signifying birth in the evening. He was baptised Thomas and was later called Joseph at his confirmation as a catholic. He was later to be better known as Tom Mboya.

Lovely African family man, Tom Mboya poses with family for photo. Courtesy: http://photography.a24media.com/

Lovely African family man, Tom Mboya poses with family for photo. Courtesy: http://photography.a24media.com/

Tom Mboya, started school in 1939 at the Kabaa Catholic Mission School in what was then the Ukamba District of Kenya. In 1942 he joined a Catholic Secondary School in Yala, in Nyanza province. In 1946 he went to the Holy Ghost College, Mangu, where he passed well enough to proceed to do his Cambridge School Certificate. In 1948, Mboya joined the Royal Sanitary Institute's Medical Training School for Sanitary Inspectors at Nairobi , qualifying as an inspector in 1950.

Tom Mboya arrived from England to a her`s welcome' He was in England to fight for Kenya`s independence. He was one of the 8 leaders elected to Legislative Council (LEGCO) in 1958. Courtesy: http://photography.a24media.com/

Tom Mboya's trade union activities started when he joined the Nairobi City Council in 1951. By 1952, he had been elected President of the African Staff Association, where he developed the association into a trade union. In 1953, Mboya ran into trouble with his employers, who were concerned about his trade union activities and was given notice of dismissal, which subsequently led him to give the City Council his notice of resignation. However, before his notice had expired, the authorities sacked him.

By this time he had helped found and register the Kenya Local Government Worker's Union , serving as its Treasurer. Later the Union became affiliated with the Kenya Federation of Labour, and in October 1953, he was elected General Secretary of the Federation, which was a full time trade union post (Mboya, 1959). While working as a trade union official, Tom Mboya enrolled for a Matriculation Exemption Certificate with the Efficiency Correspondence College of South Africa, majoring in Economics, which was aimed at improving his education (ibid, 1959). In 1955 he received a scholarship from Britain's Trades Union Congress to attend Ruskin College, Oxford, where he studied industrial management. Upon his graduation in 1956, he returned to Kenya and joined politics at a time when the British government was gaining control over the Kenya Land Freedom Army Mau Mau uprising.

Tom Mboya joined active politics in 1957, when he successfully contested and won a seat in the then colonial Legislative Council and later in 1958, founded the Nairobi People's Congress Party, which became one of the strongest parties in Kenya in the late 1950's. He was able to use his trade union links across the country to rally supporters to join the party.

In 1958, during the All-Africa Peoples Conference, convened by Kwame Nkurumah of Ghana , Mboya was elected the Conference Chairman at the early age of 28. While in Ghana he gained greater insights into nationalist and anti colonial organisational struggles that was to prove a vital asset in his struggle for his own country's independence. He was later instrumental in forming the Kenya African National Union (KANU), becoming its first Secretary General when it was founded in 1960.

Tom Mboya with other West African dignitaries at First Pan-African Congress in Accra in 1958

In 1959 Mboyaorganized the Airlift Africa project, together with the African-American Students Foundation in the United States, through which 81 Kenyan students were flown to the U.S. to study at U.S. universities. Barack Obama's father, Barack Obama, Sr., was a friend of Mboya's and a fellow Luo; although he was not on the first airlift plane in 1959, since he was headed for Hawaii, not the continental U.S., he received a scholarship through the AASF and occasional grants for books and expenses.

In 1960 the Kennedy Foundation agreed to underwrite the airlift, after Mboya visited Senator Jack Kennedy to ask for assistance, and Airlift Africa was extended to Uganda, Tanganyika and Zanzibar (now Tanzania), Northern Rhodesia (now Zambia), Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe), and Nyasaland (now Malawi). Some 230 African students received scholarships to study at Class I accredited colleges in the United States in 1960, and hundreds more in 1961–63.

When Kenya attained self-government rule on June 1st 1963, Tom Mboya became the Minister of Justice and Constitutional Affairs, a position he was able to utilise in shaping a future independent Kenya. In December 1964, Kenya became a Republic, with Mboya being appointed the Minister of Economic Planning and Development. He was later instrumental in putting together the famous Sessional Paper No.10: "African Socialism and its Application to Planning in Kenya ", which continued to be the 'guiding philosophy of the KANU government decades after Mboya' (Gimode, 1996).

Tom Mboya was gunned down on Government Road (now Moi Avenue), Nairobi CBD after visiting a pharmacy on 5th July 1969, which to many observers was seen to be the result of ethnic tensions (between the predominant Gikuyu and Luo tribes) that had gripped the nation and become a common phenomenon in post independent Kenya. Nahashon Isaac Njenga Njoroge was convicted for the murder and later hanged. After his arrest, Njoroge asked: "Why don't you go after the big man?. Who he meant by "the big man" was never divulged, but fed conspiracy theories since Mboya was seen as a possible contender for the presidency.

Doctor Chaudri desperately trying to revive just shot Tom Mboya in an ambulance. Courtesy: http://photography.a24media.com/

The mostly tribal elite around Kenyatta has been blamed for his death, which has never been subject of a judicial inquiry. During Mboya's burial, a mass demonstration against the attendance of President Jomo Kenyatta led to a big skirmish, with two people shot dead. The demonstrators believed that Kenyatta was involved in the death of Mboya, thus eliminating him as a threat to his political career although this is still a disputed matter. He was a rising star in the Kenyan political landscape and his contribution to the independence struggle and post independent era was remarkable for a man who truly had a passion for nationalism and development.

Mboya left a wife and five children. He is buried in a mausoleum located on Rusinga Island which was built in 1970. A street in Nairobi is named after him.

Mboya married Pamela Mboya in 1962 (herself a daughter of the politician Walter Odede). They had five children, including daughters Maureen Odero, a high court judge in Mombasa, and Susan Mboya, a Coca-Cola executive who continues the education airlift program initiated by Tom Mboya.

Tom and Pamela Mboya in Kianda Residence 1969

Their sons are Luke and twin brothers Peter (died in 2004 in a motorcycle accident) and Patrick (died aged four). After Tom's death, Pamela had one child, Tom Mboya Jr., with Alphonse Okuku, the brother of Tom Mboya. Pamela died of an illness in January 2009 while seeking treatment in South Africa

Quotations of Tom Mboya

From Tom Mboya on 8th December 1959 as he chaired the All Africa People’ s Conference

“African states will not tolerate interference from outside by any country – and that means power blocs that have nothing better to do but fight each other – let them do it outside of Africa.”

“We do not intend to be undermined by those who pay lip service to democracy, but have a long

way to go in their own countries.”

Tom Mboya with Bob Kennedy and his wife when they visited Kenya

From Tom Mboya on July 1st 1958 at Makerere University

“Pan Africanism is changing the arbitrary and often illogical boundaries set up by the colonial

powers in their mad scramble for Africa Many students of African Affairs are constantly asking us what sort of societies or governments we hope to set up when our freedom is won…It will not

be a blue-print copy of what is commonly referred to as western. What we shall create should be

African, conditioned and related to conditions and circumstances of Africa. It shall be enriched by

our ability to borrow or take what is good from other systems, creating a synthesis of this with the

best of our own systems and cultures.”

“Africa is a continent surging with impatient nationalist movements striving to win freedom

and independence. Apart from this struggle, there is the struggle against disease, poverty and

ignorance. Unless these three evils are defeated, political freedom would become hollow and

meaningless…the motive behind various nationalist movements should always be geared towards

the security of all our people, higher standards of living and social advancement.”

Source:http://www.tommboya.org/index.php/about/family

Prince Philip dancing with Pamela Mboya, wife of Kenya Justice Minister Tom Mboya, during the Independence Day ball. Circa 1963.

TOM MBOYA AND HOW HIS AASF ASSISTED AND BROUGHT OBAMA SNR TO HAWAII

In his review last month of “The Bridge,” David Remnick’s biography of President Obama, Garry Wills touched briefly upon the airlift that brought students from East Africa, among them the man who would become Obama’s father, to the United States.

Obama Senior Barack Obama jnr

The airlift remains a stirring endeavor for those involved and the object of cultural fascination for many others; Wills’s passing reference caught the attention of readers in excellent position to elaborate on the subject. In this Sunday’s Book Review, we publish a letter from Cora Weiss, who was the executive director of the African American Students Foundation. And now we have invited Tom Shachtman, the author of “Airlift to America” (St. Martin’s, 2009), to describe the actions that laid the foundations for the work of Weiss’s group:

Tom Mboya welcoming the 1959 airliftees aboard in Kenya.

The Kenyan labor leader Tom Mboya and the American entrepreneur William X. Scheinman began the friendship that would lead to the East African airlifts several years prior to 1959.

They met in 1956, when Scheinman helped to underwrite the American Committee on Africa’s sponsorship of Mboya’s first American lecture tour. Scheinman, a former publicist for the Count Basie band, invited Mboya to visit Harlem with him one evening; they spent all night talking together in a restaurant and emerged in the morning as fast friends. (They are buried near one another on an island in Lake Victoria.) Between 1956 and 1958, Mboya would now and then request that Scheinman buy a plane ticket from Nairobi to New York for this or that promising young Kenyan who had already won a scholarship to an American college, and he did.

By late 1958 the requests had become so numerous that Scheinman proposed to Mboya that they charter a plane to bring over the many students who needed to arrive for the academic year that would begin in September 1959. The friends formed the African American Student Foundation, which then paid for the charter that brought 81 Kenyan, Ugandan, and Tanzanian students – all that the plane could carry — from Nairobi to New York. That’s how the “airlift” was born.

Barack Obama Sr., a friend of Mboya’s and a fellow Luo, separately found his way to the University of Hawaii, but the A.A.S.F. at Mboya’s urging awarded him one of the handful of Jackie Robison scholarships that the foundation was administering. During his years at Hawaii, A.A.S.F. assisted Obama Sr. with additional small monetary grants, as it also did between 1959 and 1963 with hundreds of other promising young men and women, including among them the future Nobel Peace Prize laureate, Wangari Maathai.

TOM SHACHTMAN

Salisbury, CT

source:http://artsbeat.blogs.nytimes.com/2010/05/07/how-obama-sr-came-to-hawaii/?_r=1

Martin Luther King`s letter of Acknowledgement to Tom Mboya`s financial assistance from Luther to enable Kenyan student study in USA

Tom Mboya, [M.?]L.C. 8th July

P.O. Box 10818 1959

Nairobi, Kenya

Dear Tom Mboya:

I am in receipt of your very kind letter of recent date thanking the leaders of

the Southern Christian Leadership Conference for the dinner in your honor. I

should have written you before you wrote me to thank you for giving us the opportunity

to honor ourselves in bringing you to Atlanta. Because of your distinguished

career and dedicated work, the honor was ours and not yours. I will

long remember the moments that we spent together. I am sure that you could

sense from the response that you gained all over the United States that your visit

here made a tremendous impact on the life of our nation. Your sense of purpose,

your dedicated spirit, and your profound and eloquent statement of ideas

all conjoin to make your contribution to our country one that will not soon be

forgotten.

Thank you for your very kind comments concerning my book, Stride Toward

Freedom.* This book is simply my humble attempt to bring moral and ethical principles

to bare on the difficult problem of racial injustice which confronts our nation.

I am happy to know that you found it helpful. I am absolutely convinced that

there is no basic difference between colonialism and segregation. They are both

based on a contempt for life, and a tragic doctrine of white supremacy. So our

struggles are not only similiar; they are in a real sense one.

I am happy to know that you will have a student enrolled in Tuskegee Institute

in the next few months. I will be happy to make some move in the direction of assisting

this student. Please give me some idea of the amount of money that he will

need over and above the aid that he will get from Tuskegee Institute itself.' Also

let me know whether the money should be sent directly to you or given to him in

person.

Sincerely yours,

Martin L. King, Jr.

MLK:mlb

With warm personal regards, I am,

TLc. MLKP-MBU: Box 26.

2. Mboya had written that he had never found himself "so completely captured by a book and ideas"

(Mboya to King, 16 June 1959).

3. In a 3 I July reply, Mboya indicated that the student would need $1,000. King arranged for Dexter

Church and SCLC to support Nicholas W. Raballa, who was among an initial group of eighty-one

Kenyan students flown to the United States on 7 September 1959 under a program organized by Mboya.

More than one thousand Kenyan students would eventually take part in the "airlifts" to the United

States (S. E Yette, "M. L. King Supports African Student," Nms of Tuskgee Zmtibfe, December 1959;

see also King to Raballa, 1 1 January 1960, and photograph of King and Raballa, p. 87 in this volume).

MBOYA: TRADE UNIONIST AND A GREAT SON OF AFRICA

by J.D. Akumu is a pioneer trade unionist and once served as the Secretary General of African Trade Unions

Tom Mboya will always be remembered as a great trade unionist and a great son of Africa. He was a self-made man, he worked hard, was generous to the poor and a strong Pan-Africanist who was committed to the total liberation of Africans in Africa, and Africans in the Diaspora. He presided over the first All African People’s Conference and was in touch with the African leaders in the Diaspora like A. Philip Randolph of USA, and trade unionist Michael Manley of Jamaica.

Mboya welcomed to a function by Indian premier Nehru

I met the late Mboya in 1952 when we were both taking part in a debate at the Mbagathi Postal Training Centre. He was then working with the Nairobi City Council as a health inspector. In 1953, when Mzee Kenyatta and his colleagues were detained by the colonial administration; they invited active student leaders including Mboya, the late W. W. Awori and the late Walter Odede to take over leadership of the Kenya African Union (KAU). We remained in touch until the Kenyan African Union (KAU) was banned and Odede detained in Kwale.

Being an employee of the City Council, Mboya joined the City Council Staff Association and transformed it to a trade union (Kenya Local Government Workers Union, KLGWU). By then, the colonial authorities only allowed African workers to form staff associations. Mayor Reggie Alexander and city authorities refused to recognise the union. Mboya took them to the tribunal- a judicial inquiry formed to look into the relations between the Nairobi City Council and the Nairobi branch of KLGWU, and won the case. One of his colleagues during this local government struggle, the late James Karebe, remained his friend for life.

In 1952, his union joined the Kenya Federation of Registered Trade Unions and he took over as Secretary-General in place of Aggrey Minya. He and his group changed the national union’s name to the Kenya Federation of Labour (KFL). Mboya expanded the international platform, which Minya had started, by continuously attacking colonialism and the state of emergency.

The KFL became the voice of Kenyan Africans during the emergency when all political parties were banned. It is KFL that led the struggle for the release of detainees, and for liberty.

In 1956, while in Europe, Mboya made a speech which attacked detention without trial and the despicable ways in which Africans were treated by the British colonial authorities. This prompted the settlers in the Legislative Council to move a motion seeking to ban the KFL. It took Mr Arthur Ochwada, who was then the Acting Secretary-General of the KFL, to negotiate a compromise that saved the federation.

In his capacity as KFL Secretary-General, Mboya settled the dock workers major strike. He also mobilised the International Plantation Union to support the late Japheth Gaya and Jesse Mwangi Gachago to organize plantation workers in Kenya. As a son of a plantation worker, he was very keen on the unionisation of workers. His father Leonard or ‘Leonardus’ Ndiege, was a sisal cutter in an estate farm belonging to Sir William Northrup McMillan, at Kilimambogo, a few miles east of Thika.

Tom Mboya with his wife and kids

What is Mboya’s legacy in Kenya?

Mboya helped to build the present Cotu (K) headquarters. It is from that building that Mzee Kenyatta set off to address his first public rally on 20 October 1961 at City Stadium after his release from detention.

Mboya helped to build the present Cotu (K) headquarters. It is from that building that Mzee Kenyatta set off to address his first public rally on 20 October 1961 at City Stadium after his release from detention.

Mboya laid the ground for the present National Social Security Fund which he left in the hands of Ngala Mwendwa. He worked on the Tripartite Agreement, which has been used as a guideline not just in Kenya but in Africa.

In East Africa, Mboya visited Tanzania and helped Hon Rashid Kawawa to form the Tanganyika Federation of Labour; while in Uganda, he worked with others to create the Uganda Trade Union Congress (UTUC).

Mboya was also for a while Africa’s Regional Representative of the International Confederation of Free Trade Unions. At that level, he was instrumental to the trade union movement throughout the whole of Africa.

In 1958, Mboya sent Gideon Mutiso and I to Accra to attend a preparatory committee of the All African People’s Conference. Later that year (1958) Nkrumah invited Mboya and Dr Julius Gikonyo Kiano to the All African People’s Conference, which brought Pan-Africanism home. Before then all Pan-African meetings had been held outside Africa.

Mboya had a great commitment to Pan-Africanism. It must be remembered that when he was assassinated, he had just returned to Kenya from Addis Ababa, where he had been attending a meeting of the Economic Commission for Africa.

There are many questions still unanswered. Why was he assassinated? Some have claimed that it was because of the succession battle between Mboya and a group of politicians known as the ‘Kiambu Mafia’.

If there had been a free and fair contest, would it have been possible for him to lead Kenya? Many people believe he would have won. Would Kenya have fared better under him? Yes: He hated corruption and was against acquisition of massive individual wealth. He believed in fighting poverty and unemployment. We in the trade union movement have remembered him by building the Tom Mboya Labour College. I am glad the present Cotu (K) Secretary-General, Mr Francis Atwoli, is renovating it in an attempt to elevate it to a worker’s centre for high education.

I am surprised that other Kenyans, including hundreds who benefited from Tom Mboya’s airlifts to America, have not thought of a proper memorial for this great son of Kenya.

Tom and I argued, and at times disagreed ideologically, but we remained friends and we indeed recognised and appreciated each other’s points of view.

I want to thank the Kenya National Commission on Human Rights for arranging this function. I hope you can arrange similar events for other deserving heroes as well.

TOM MBOYA: A POLITICIAN IN PRE-INDEPENDENCE AND POST-INDEPENDENCE KENYA

by Hon. Jeremiah Nyaga. Nyaga was born in Embu 1920. Educated in Makerere University College, he was a member of the LegCo between 1958-1962. He served at various times in the 1960’s, 1970’s and 1980’s as a Cabinet Minister for Water, Agriculture and Livestock Development

My assignment here today is to describe “Tom Mboya as a Politician in Pre-Independence and Post-Independence Kenya,” particularly the role of Mboya and myself played when Kenyans were demanding the following:

• The right to self-governance

• The termination of all forms of racial discrimination perpetuated by the then ruling Mkoloni/Mwingereza – who referred to our motherland as ‘Kenya Crown Colony and Protectorate’ while discriminating against the Mwafrika in many ways such as segregated residential areas in Nairobi, segregated social places that saw Europeans enjoy the most privileged restaurants, unequal provision of education, health facilities and other sectors such as employment, salaries and promotions.

Let me get to my assignment about my time in politics with Mboya, especially from 1956 to the time he was assassinated along the then Government Road, now Moi Avenue, outside the Chahhni Pharmacy, in broad daylight.

I first met Tom in 1956 during our meetings at the office of the Civil Servants Union in Kariokor/Starehe – near his residence. By then, I was an Assistant Education Officer (A.E.O.) in Kiambu and acting secretary for civil servants, Kiambu Branch. Before my Kiambu posting, I had been teaching at the then Government African School and Teacher Training College Embu/Kangaru as Vice-Principal.

I was in Kiambu during the state of emergency arising out of the Mau Mau Rebellion against the Mkoloni’s rule. The Kikuyu, Embu and Meru were the most affected by the restriction rules, which were mostly applied in Central Province and Nairobi In 1956, the Mkoloni relaxed the governing system in Kenya and created eight constituencies for Africans. The eight constituencies were filled through a franchised election in 1957. The eight African Members of the Legislative Councils (MLCs) elected in 1957 demanded that Africans, who were the majority inhabitants in Kenya, should have more representation in the Legislative Council

(Legco). This was done in 1958 when I and five other Africans were elected, thus increasing the number of Africans in the Legco to 14.

We worked in unity as MLCs within our group, the African Elected Members Organisation (AEMO) with Oginga as the chairman and Mboya the secretary. We started rather well as AEMO, but somewhere down the line, there were differences in opinions among individual MLCs, whichinterfered with our team work. Despite the minor differences, God was with us and we were successful to a certain point and worked progressively on our Lancaster gains.

During all this time, Mboya was one strong man in all the struggles we had and played a major role in the following areas until Kenya got its independence in 1963:

• The revocation of the state of emergency,

• The release of Jomo Kenyatta and his fellow detainees,

• The removal of restrictions and the end of villagisation in Central Province and Nairobi, movement (kipande) permits and the removal of racial discrimination in all forms,

• The end of colonial rule and for Mwafrika to be free to govern his country.

Mboya was particularly active in making arrangements for the elimination of racial discrimination against Africans and the support for African demands. For example, we visited Lokitaung where five freedom fighters (Jomo Kenyatta, Paul Ngei, Bildad Kaggia, Ochieng Oneko and Kungu Karumba) were incarcerated. Further, he arranged for African students to study in friendly foreign countries such as USA, India, and some European countries.

Tom did his best!

He deserves more recognition than he has been accorded.

We should have a statue of Tom in the City of Nairobi.

We should know and live up to the aims and objectives of our national fighters/founders (the Mau Mau freedom fighters and detainees).

Time does not allow me to tell you the role Tom played to command support from friendly European, Asian and African countries such as Tanzania through Mwalimu Nyerere, Uganda through Obote, Gold Coast (Ghana) through Kwame Nkrumah and Nigeria.

People like the late Joseph Murumbi and Pio Gama Pinto should also not be forgotten. Kenyan lawyers such as Fitz de Souza and Argwings Kodhek. People who supported Kenyans during the fight for Uhuru should be accorded due recognition regardless of race or colour.

We Kenyans must remember the valuable advice of our freedom fighters:

We wanted self-rule to govern ourselves

We should do this through Love, Peace and Unity

Assassinations are not what we fought for

Tribalism is not in accordance with Peace and Unity

Uhuru na kazi is our goal, not the present factionality and political infighting

God is in command if we follow and practice our prayerful National Anthem

“Ee Mungu nguvu yetu

Ilete baraka kwetu

Haki iwe ngao na mlinzi

Natukae na undugu, amani na uhuru

Raha tupate na ustawi”

Mboya welcomed aboard British war ship

NB: One of Tom’s valuable contributions was in connection with the design of Kenya’s National Flag, whose colours represented the Kenya African Democratic Union (Kadu) and the Kenya African National Union (Kanu) party colours, and wananchi’s shield and spears for defence.

There is a book titled “Tom Mboya, the Man Kenya Wanted to Forget.” Perhaps it should be renamed “Tom Mboya, the Man Kenyans Want to Remember.”

MBOYA AS MINISTER

By Harris Mule

I am truly honoured to be among this distinguished panel of speakers in honour of one of the greatest sons of Africa and one of the foremost architects of modern Kenya. At a young age of 39, Tom Mboya had accomplished more than most human beings ever hope to attain in a lifetime. He had built one of the most effective trade union movements in Africa and had effectively used the movement as a tool for independence. In his mid-twenties, he was the youngest Member of Parliament (Legislative Council) representing a multi-ethnic constituency. He was an eloquent spokesman of the interests of the downtrodden. In an eulogy by President Jomo Kenyatta at Mboya’s requiem mass, “Kenya’s independence would have been seriously compromised were it not for the courage and steadfastness of Tom Mboya.”

To Tom Mboya, independence was not an end in itself. Unlike Kwame Nkrumah, who exhorted his followers to “seek the political kingdom first, and all the other things will be added to them,” Mboya viewed independence as a means of creating a modern, sovereign state, giving Kenyans a sense of nationhood, and of engendering prosperity with equity to fight the ignorance, poverty, and disease. This comes out very clearly in his book, Freedom and After. As the Minister for Labour, Minister for Justice and Constitutional Affairs, and most notably, Minister for Economic Planning and Development, Tom Mboya strove tirelessly, selflessly, and courageously to achieve this dream.

It is in the above context that we should look at Tom Mboya as Minister. And in so doing, we should look at his multiple roles as a man with a vision for Kenya, a policy maker, an institution builder, and a manager.

Tom Mboya was a man with a vision for Kenya. I have already alluded to his conviction that independence was a means to other ends. His vision is best captured in the Sessional Paper No. 10 of 1965, on African Socialism and its Application to Planning in Kenya. This paper visualised Kenya as a nation with a growing economy and citizens enjoying higher and growing per capita income equitably distributed. It was the vision of a nation of healthy and educated individuals productively employed to better their lot and those of their families and the nation as a whole. It envisaged the emergence of modern and vibrant nation firmly rooted in the best of the traditions and cultures of African society. It saw a nation at peace with itself and its neighbours.

Tom Mboya with Jomo Kenyatta

To achieve that vision, policies had to be put in place in relation to ideology, international relations, economic structure, ownership of property, and systems of economic sanctions and rewards. The hottest debate then was on ideology. The world was raven by-“isms”: capitalism, communism, scientific socialism, Fabian socialism, African socialism, and many other-“isms”. Tom Mboya pushed for a variant of African socialism, which advocated for a mixed economy–a mixed ownership of productive assets, an economy open to international trade and capital, and an economy guided by principles of efficiency, equity, and fairness. By sheer force of personality, persuasiveness, and political astuteness, Tom Mboya carried the day. And this document has served Kenya well. It was, and still remains, a masterpiece of ideological architecture. It provided flexible guidelines in charting the economic future of the country, and spared the country the ideological turbulence which has been the fate of many countries in Africa and beyond during the last 15 years.

Tom Mboya was a policy maker per excellence. Policy making is about making choices. And the choices are always difficult. To many policy makers, it is tempting to opt for short-term political gain at the expense of long term national benefits. Tom Mboya always opted for policies which would confer long-term benefits to the greatest number of Kenyans, and to the nation as a whole. A few examples will illustrate this point:

In formulating the first National Development plan, 1964 – 1970, hard choices had to be made between public consumption by way of free education, free health, and housing or public investment in agriculture, infrastructure, and the enterprise sector. Although clearly desirable at that time, the economy could not afford free social services. Tom Mboya, therefore, pushed for free education at tertiary level, both Forms V and VI and at university. This was not only affordable but it also met the immediate manpower needs for the budding economy. Public investment was directed towards the productive sectors.

The results were impressive. Kenya’s Gross Domestic Product grew at more than 7 per cent annually in real terms and more than 10 per cent in nominal terms. Government revenues grew by more than 20 per cent annually in nominal terms. With a growing economy and government revenues, the government and households could afford to pay for education and other social services and by early 1970s, primary school enrolment was nearly 100 per cent.

A second example was on housing. Tom Mboya represented Kamukunji Constituency, which then had the biggest slums in Kenya. He was under pressure to demolish the slums and replace them with modern high-rise apartments. This was politically appealing but financially unaffordable. The urban housing problem is first and foremost an income problem. There is no point in building good houses if the poor cannot afford to own, rent, or maintain them. Instead of pushing for unaffordable houses, Tom Mboya opted for a site and service scheme, which provided the poor with serviced plots and encouraged them to build decent houses for themselves.

Perhaps the biggest policy challenge to Tom Mboya was on family planning. Kenya’s population was growing at 3.2 per cent annually in 1960s. It was clear that the economy could not provide a decent standard of living with that rate of population growth. But as a practising Catholic, family planning posed an ethical dilemma to Tom Mboya. He asked the economists in the Ministry to prepare a concept paper on family planning outlining clearly its rationale, and its pros and cons. He pondered over it, was convinced of its merits, and discussed it with Cardinal Maurice Otunga. His intention was not to persuade the Cardinal to accept family planning, but rather for the Cardinal to at least understand the reasons why Tom Mboya would be pushing for family planning. Despite his faith, Tom Mboya was one of the few voices promoting family planning in 1960s.

The examples, enumerated are illustrative of Tom Mboya’s approach to policy making, an approach informed by political courage, rationality, analysis, and long-term well being of the majority.

Tom Mboya was equally aware that policies do not operate in a vacuum. Policies are formulated and implemented within an institutional framework. He was, therefore, an institution builder. As the Minister for Labour, Tom Mboya fashioned industrial relations institutions, including Cotu and the Industrial Court, which have served this country well. As the Minister for Justice and Constitutional Affairs, he domesticated the Lancaster Conference Constitution, which, despite its subsequent amputations, has served this country for more than 40 years. And as the Minister for Economic Planning and Development, he created a vibrant institution which has stood the test of time as evidenced by the presence of the Minister for Planning and National Development with us here today.

Finally, Tom Mboya was the ultimate economic manager. He brought to bear all his intellectual brilliance, capacity for hard work, political skills and clout in translating policy decisions into action. He was accessible to his staff, no matter how lowly. I recollect that in mid 1960s, I was a mere economist, which in civil service hierarchy, is seven grades below a minister. In a normal bureaucracy, it is rare for such a junior officer to have access to a Permanent Secretary, let alone a minister. But with Tom Mboya, we all had free access to him as long as we had something useful to say.

He was a good listener. He read all the memos, briefs, and policy documents very carefully, asked searching questions, internalised the information, and acted on it. He took a maximum of three days to react to any memo from any officer. But one had to do his homework. Tom Mboya did not tolerate mediocrity. If one did not perform, he had no place in Tom Mboya’s team.

Despite his pro-active management style, Tom Mboya respected separation of civil service from politics. The job of a civil servant was to provide accurate and timely information and professional advice. It was up to him to assess its political feasibility. And if the advice was professionally sound, technically feasible, and economically viable, Tom Mboya invariably accepted it and ensured that it was implemented. For a young professional, this was an exhilarating experience. There is nothing more satisfying to anyone than seeing his ideas translated into national development agenda.

Tom Mboya rewarded merit and hard work. One of the major shortcomings of Kenya’s civil service is its tendency to under-reward professionals. This was still the case in the 1960s. In order to motivate his professional staff, the first thing Tom Mboya did as a Minister for Economic Planning and Development was to ensure that an attractive scheme of service for economists and statisticians was put in place. He also ensured that those among his staff who were competent and dedicated were rewarded with accelerated promotions. By the same token, the lazy and incompetent were weeded out.

And as we celebrate this ‘Evening with Tom Mboya,’ let us recollect a few highlights of his life as a minister. Let us remember his commitment to nation-building and his passion for promoting the dignity of the African and improving the well-being of all Kenyans. Let us remember his many talents and his willingness to put them to the service of his country, his political courage and willingness to take hard economic choices in the face of opposition by vested interests, and his capacity for hard work.

To Tom Mboya, development was nothing other than intelligent and efficient application of effort. In his eulogy during Tom Mboya’s requiem mass, Samuel Ayodo extolled Tom Mboya’s capacity for hard work. That is a befitting legacy of Tom Mboya to all of us today.

Tom Mboya would have been 75 today had his life not been cut short so cruelly in 1969. Those responsible for that dastardly act were cowards. They were incapable of competing with Mboya in the political arena. Had he lived, he would have contributed enormously to this country. But even in the short span of seven years that he served as a minister, his contribution to Kenya, then and now, is unequalled. As a nation, we are still living off the legacy of policies and institutions that Tom Mboya bequeathed us. For that we should be grateful.

Tom Mboya would have been 75 today had his life not been cut short so cruelly in 1969. Those responsible for that dastardly act were cowards. They were incapable of competing with Mboya in the political arena. Had he lived, he would have contributed enormously to this country. But even in the short span of seven years that he served as a minister, his contribution to Kenya, then and now, is unequalled. As a nation, we are still living off the legacy of policies and institutions that Tom Mboya bequeathed us. For that we should be grateful.

THOMAS JOSEPH MBOYA AND POLITICS AS A VOCATION

By Prof. Nyong’o, a professor of Political Science, served as the Minister for Planning and National Development under the NARC (National Rainbow Coalition) administration

The last public position that Thomas Joseph Mboya held was that of the Minister for Economic Planning and Development of the Republic of Kenya. As the current holder of that portfolio in the last 23 months, I stand in awe at the accomplishments of the founding father of my ministry. I am sure that I speak on behalf of all the officers in my ministry when I state that he set a standard of professional excellence that remains a challenge to all of us in Kenya to this day.

Tom Mboya distinguished himself as a leading thinker of development planning both in Africa and the rest of the developing world. He published articles and books on development problems facing Africa that are still relevant today. He defended the development policies that Kenya adopted after independence with intellectual logic and an eloquence that is hard to match. His was always going to be a difficult act to follow. I, therefore, feel at once humbled and greatly honoured to have been asked to speak at this occasion to commemorate the life of one of the most respected statesmen in the history of independent Africa, Thomas Joseph Mboya.

When the Kenya National Commission on Human Rights invited me to speak at this historic occasion, they suggested as the title for my lecture “Tom Mboya: The Ultimate Politician and Role Model for Today’s Politicians.” I accepted the invitation to speak on that title.

But upon reflection, I thought the term “ultimate politician” as opposed to the “ultimate statesman” had the ring of a hard-driven political self-interest that was alien to Tom Mboya’s career as an African nationalist and Kenyan statesman. Ultimate politicians just have only one drive; political power. To them politics is an end in itself. I, therefore, chose the title “Tom J. Mboya and Politics as a Vocation” in the sense that Max Weber uses vocation in a famous essay entitled “Politics as a Vocation”. In this context, vocation refers to a personal calling to serve a cause, a greater cause than oneself; a call that is driven less by what we normally call politics, but by a noble social goal.

This is what I see in the public life of Tom Mboya. A person with a sense of vocation, which motivated him to serve a cause because it was the right thing to do, irrespective of the personal risks involved. This sense of public service on the basis of moral principle is now sadly alien to a large section of Kenya’s political class. It is sad for our country that we now have a young generation for whom this idea is foreign, to whom public service without personal profit sounds outlandish, even cynical.

Mboya had the calling to do everything he could to restore African dignity at a time when colonialists, racists and imperialists – for that is what he called them – had doubts about an African’s entitlement to full human dignity, to the political rights that were enshrined in the constitutions of our colonial rulers, and that Africans knew before colonial rule. Before and after independence, Mboya told us that tribalism stood in the way of this mission. For that, he paid with his life. That is the ultimate price for any leader who believes in a vocation. Abraham Lincoln paid that same ultimate price. So did Mboya’s close friends, the late President John F. Kennedy of the US, and the late Dr Martin Luther King.

Tom Mboya in the World Stage

In ‘Julius Caesar’, the conspirators who would assassinate Caesar express their envy of him, and their frustration, in the following words:

“Why, Man, He doth bestride the narrow world like a Colossus

And we petty men walk under his huge legs and peep about

To find ourselves dishonoured graves”

In their personal insecurities, petty men and underlings think that eliminating a political colossus will solve their problems by elevating their stature on the world stage. It never works that way. Brutus was not to rule Rome. He perished in desolation, in a dishonoured grave, hounded by the ghost of the Roman emperor he had murdered.

But to describe Tom Mboya as an African colossus, a statesman who stands above his peers in African history would be just another cliché and would do a great injustice to the finer details of his legacy, which we celebrate this day.

When the world looks at the history of post-independence Africa, it will pay tribute to Tom Mboya for the role he played in making that history. Tom Mboya was the most polished and most articulate spokesman of African nationalism to the rest of the world in the 1950s and 1960s. He explained to the sceptical and the cynical in the West, that the dramatic events unfolding in colonial Kenya under the emergency, the Algerian war of independence, and the struggle against apartheid were one of a kind. Colonial oppression based on white supremacy had pushed Africans to a corner, he said. When African voices were silenced and racial oppression increased, any violent resistance, which arose, should be attributed to the oppressor not the oppressed. By and by the world came to rely on his clarity of thought in interpreting the new Africa. All this before he was thirty years old!

Take the victims of torture in the Mau Mau detention camps here in Kenya. From about 1956 onwards, Mboya used his position as a member of the Legislative Council to forward evidence from detainees to sympathetic Labour MPs like Barbara Castle and William Bottomley. A bond based on trust developed between his activism for nationalism in Kenya, the Labour Party and the anti-colonial movement in the United Kingdom. The colonial authorities in Kenya privately complained that the opposition “Labour Party in Britain will say nothing in Kenya unless they have consulted Tom Mboya”. So they tried as best as they could to destroy his personal integrity and standing with the Labour Party. But they failed.

It was not only colonial brutality in Kenya that concerned him. When the Sharpeville Massacre of 1961 took place, Tom Mboya was among the first African leaders to call for the immediate expulsion of apartheid South Africa from the Commonwealth. He and other African leaders prevailed. South Africa was expelled from the Commonwealth that year.

Tom Mboya and Prince Charles at Kenya`s Uhuru celebrations. Courtesy: http://photography.a24media.com/

Tom Mboya and Prince Charles at Kenya`s Uhuru celebrations. Courtesy: http://photography.a24media.com/

In considering Tom Mboya’s performance at the international scene in the cause of African nationalism, nothing stands out in those early days as much as his election as chairman of the All-Africa People’s Conference in Accra, Ghana, at the age of only 28. This conference had been called by the first president of independent Ghana, the late Osagyefo, Dr Kwame Nkrumah, to adopt a strategy to accelerate decolonisation in Africa, and to chart the way towards the unity of the new independent African states. This meeting was the precursor to the Organisation of African Unity, which was born five years later in Addis Ababa. It was attended by the “who is who” in African nationalism at the time – Frantz Fanon representing FLN from Senegal, Gamal Abdel Nasser from Egypt, Joshua Nkomo from the then Southern Rhodesia, Patrice Lumumba who was to become the first prime-minister of independent Congo, Holden Roberto of Angola, and many others.

At a very young age, Tom Mboya was already presiding over African nationalist history in the making. Books are still being written on what that conference meant for Africa.

Colin Legum, the dean of the African Press corps at the time, made acquaintance with Mboya and respected his opinions for all time. Mboya had come to the notice of the world. It was after this event that one of Africa’s premier journalists in Britain, Alan Rake, wrote his short biography of Mboya entitled, Tom Mboya: Young Man of Africa. Notice that fame came to him. He did not go out to publicise himself, or to demand adoration from sycophants and praise-singers which later became the norm here in Kenya.

Every subject that concerned African peoples whether in Africa, or the diaspora, became an issue of personal concern to him. He made contacts with the late Dr Martin Luther King when he was waging his campaign to register African-Americans to vote in Montgomery Alabama in the late 1950s. He was close to the African-American trade unionist A. Philip Randolph and Jackie Robinson, the first black American to play for a national baseball club in that country. He was a friend of Harry Belafonte and dozens of others. All of them played a major role in the Kenya Student Airlift Programme starting in 1958. In laying the foundation of the trade union movement in Kenya as we know it today, he linked it to the world’s labour movement in the International Confederation of Trade Unions (ICFTU) in Brussels and the AFL-CIO in the United States.

To the ire of the colonialists in Kenya, Mboya exposed their shenanigans to the international press. He wrote for The New York Times and The Washington Post, and also gave interviews to countless regional newspapers in the United States of America. In the political arena, his debating skills in the colonial Legislative Council and in the Parliament of Independent Kenya were widely acknowledged as among the world’s best – even by his opponents. He had a rare intellect - as a writer on Kenyan and African nationhood, African socialism, the problems of economic development and poverty, non-alignment and the international economic relations between ex-colonial territories like Kenya, and the developed world. He was at home in the quietness of his family, nation-building in Kenya, the politics of Africa, or as the first African guest on American television in the NBC programme, “Meet the Press”. As Cicero would have it, he was neither a Kenyan Luo nor an African politician, but a citizen of the world.

All the activities Tom was involved with at the international level were for a cause he believed in, not for money. Again this comes as a big surprise to a generation of Africans who have witnessed politicians fighting the most vicious wars to make money on the backs of poor Africans, at times even stealing money intended for starving refugees. Such people have missed their vocation. And Africa is the poorer for it. What a contrast to the vision Tom Mboya fought for in the 1950s and 1960s.

The Genesis of Personal Commitment

After his studies at Mangu High School, Mboya went in 1948 to study for the job of a Sanitary Inspector at the then Jeans School, now Kenya Institute of Administration (KIA). He had no problems completing and passing the course and was awarded a certificate by the Royal Sanitary Institute.

But there is a story in his autobiography Freedom and After which, I believe, explains his life-long commitment to fight for African freedom and human dignity. At one point, as Mboya tells it, he was left by his European boss at the counter to inspect milk from the farms coming into Nairobi. Seeing a black man in charge of the station, a white woman asked in anger “Is there nobody here?” meaning that he was nobody, the European boss was somebody. Fanon once wrote that in colonial societies, whites colonialists looked at Africans as hard as they could but, could not see a human being in them. Here is some evidence of this.

With such humiliation should we be surprised that Mboya took it upon himself to organise the first City Council of Nairobi African Staff Association? In later years, his enemies were to accuse him of accepting western support. If anything, he was offering his time and money free. Here and in later life, nobody paid him to unionise African workers. It came from an inner passion that abhorred colonial indignities African workers suffered in colonial Kenya.

This is the difference between him and your regular power-seeking politician, which I spoke about earlier.

The same applies to his personal sacrifice in founding the Kenya Local Government Workers Union (which caused him to be fired by the City Council), and the Kenya Federation of Labour.

Into Nationalist Politics

If we understand why Africans were pained by the “Is there nobody here” colonial attitudes, then we can understand why in the case of Tom Mboya, politics of unionisation led to politics of liberation from colonial rule. Again in Freedom and After, he narrates how during Operation Anvil in April 1954, he and other Africans were required to squat on the street (Victoria Street then), their hands above their heads for hours, while the police picked up Kikuyus for detention. I have already mentioned his work for the sake of those detainees. Giving the Mau Mau Emergency as an excuse, the colonial government did not allow the formation of African political parties until 1955. Even then these were restricted to districts rather than national level.

Upon returning from a year at Ruskin College, Oxford in 1956, Mboya went flat out to organise the Nairobi Peoples Convention Party. Notice that its title echoed that of Nkrumah’s Convention Peoples Party. From the start, it was strategically organised on a national basis, to make it easier to form a nationalist party when the right time came. In the following year, Mboya won the Nairobi African seat for the Legislative Council.

As we reflect on the political achievements of Tom Mboya, tonight, let us recall two significant observations that have never received as much public attention as I have always thought it should.

First, throughout his political life, Tom Mboya was elected to our national legislature by voters who did not come from his ethnic group – the Luo. Secondly, he worked hardest not for his social class which was the new African middle-class that arose after the Second World War, but rather for those less privileged than he was – the working class and those who, for some reason or other, were unable to complete high school or university education. This is the sense of vocation I spoke about at the start of this lecture. Again, there was no money for him in any of these thankless tasks. No “kitu kidogo” that was to corrupt our country later. How many of our leaders today can boast of a record of public service like this?

Tom had that rare trait in Kenya politics today – the capacity to appeal to all Kenyans regardless of ethnicity or race. On the eve of our independence from Britain in 1963, Kanu (which was a very different party from what it is today) decided to field Tom for the Nairobi Central seat – as it was then. This was to be the last constituency he represented in Parliament.

Why did Kanu leaders – Kenyatta, Odinga, Gichuru and Mwainga Chokwe – want Mboya to represent a constituency in Nairobi Central? It is because, as they judged rightly, he was the only African politician who could appeal to the Kenya Asian voters. As it turned out, they were right. He won the seat by a wide margin.

Mboya’s capacity to win the confidence of voters from racial and ethnic groups other than his own was already evident in the 1957 and 1961 elections when he won the Nairobi East seat (as it was known then) even though the voters were predominantly Kikuyu. In 1960, Kenyan nationalists brought from Lancaster House, the MacLeod Constitution. It provided for the first election, which brought Kenya an African majority parliament the following year. His opponents in Nairobi East tried to use tribalism to campaign against him. It backfired. Campaigning with the symbol of “Ndege” to symbolise his achievements in sending Kenyan students abroad through airlifts, he won the election with a landslide – 29,000 votes against his opponents 3,000. This landslide came from those Kikuyu ex-detainees he had defended in the 1950s, and the “mama mbogas” of Eastlands, the Luo, Kamba, Luhya and Mijikenda labourers who knew the record of his work from the days of the Local Government Workers Union, and the KFL.

In view of the ugly tribal conflicts that arose after his assassination in 1969, it is worth remembering that ordinary wananchi in Kariakor, Majengo, Hamza, Bahati, Ofafa Kunguni, Mbotela and Kariobangi had no problem at all voting for him. As always, we see that tribalism was a disease that started from the top of the political leadership. It still is. As we try to rebuild our country from the ashes of decades of dictatorship and tribal conflict, we should never forget this. We as leaders have the capability to unite or divide our people – be they Africans, Asians or Whites, Christian, Hindu or Muslim. Tom chose unity and he showed us the way in word and deed.

Tom Mboya chatting with Harry Belafonte

Having found it impossible to continue into university education after Mangu, Tom was determined to do as much as he could to ensure that those in similar social circumstances did not suffer his fate. Not that he stopped his education when he left school. After Jeans School and Oxford he read prodigiously. He could hold his own in debates with the best of scholars. His withering on-stage demolition of the anti-Africanisation report by 18 economists at the University College, Nairobi, in 1968 is still remembered as one of finest intellectual debates in Kenyan academic history.

He did not have the insecurity that some politicians have of people better educated than they are. He was not part of the PhD (i.e. Pull Him Down) brigade – that is, those who treat their intellectual betters with fear and who always try to pull them down to the lowest common factor.

That is why he went to great lengths to ensure that Kenyans who lacked university education at home could get it abroad, and especially in the US where he had friends like the Kennedy Foundation and African-American Association. Today, Kenyans seem to respect anyone with money no matter how he or she earned it. Let us never forget that under our best nationalist leaders like Tom Mboya, what you knew mattered more than what you owned. Knowledge, not money, is what pushes a country forward. The sooner we retrace our steps to what Tom taught us the better for Kenya.

By Way of Conclusion

I do not want to leave you with the impression that as a politician, Mboya had no faults. All great statesmen do. For all his greatness, Churchill was compulsive and he meddled unnecessarily with the armed forces. A saint that he was, Gandhi would not hear of partition in India even when it was a reality. Mboya had very little patience with ill-informed, ill-read politicians who loved empty slogans with no substance behind them. He was such a sharp debater that he often left his opponents licking their wounds and made no apologies for it. Yet in spite of all that he served his country well.

That is why this evening we are commemorating one of the saddest moments in the history of post-independence Kenya and indeed of Africa – his death in the hands of an assassin in 1969, at the tender age of 39. For when he was shot, the sound rang around the world. Radio stations in the US broke the news with shock and disbelief. He had just returned from a tour of the US. In the following morning, his assassination was front page news in The New York Times, The Times of London, Washington Post, Le Monde and the Times of India - to mention but a few. Television stations around the world extensively covered it. The British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) lead item in its international news that day was the following: “One of Africa’s youngest and most brilliant politicians, Mr Tom Mboya of Kenya has been assassinated.” And the BBC has never been accused of hyperbole.

The world mourned his passing. And all those who loved him wept with his young family.

Upholding the dignity of Africans in the world.

Nationalism and nation-building.

Public service without discrimination.

Fighting tribalism and racism at once.

Cultivating one’s intellect as a virtue in its own right.

African development and African socialism.

The benefits of a mixed economy, as he called it.

These were the watchwords of a world statesman who took politics as a calling, not as a business.

“Here was a man take him all in all”

We shall not behold the likes of him again”

–Hamlet.

PLANNED ASSASSINATION OF TOM MBOYA

UNDERWRITING MBOYA AND HIS Labor Federation was a natural strategy for the U.S. in Kenya during the '50s and early '60s. It advanced responsible nationalism; and it was painless, because the employers faced with higher wage demands were British, not American. By 1964, however, American investments, which would reach $100 million by 1967, were becoming significant, and some of the Kenyan union demands began to lose their charm. But even more important, 1964 also brought dangers of "political instability" serious enough to make radio communications with the Nairobi Embassy eighth highest on the State Department roster for the year.

Zanzibar revolted and Tanzania's Nyerere was nearly overthrown. Rebellion was spreading through the Northeast Congo, and Kenya lay astride the natural supply route. The CIA decided that a new approach was in order.

In June 1964, U.S. Ambassador to Kenya William Attwood met with Kenyatta and agreed that Western labor groups would stop subsidizing Mboya and the KFL; for balance, Kenyatta assured him that Russian and Chinese aid to the leftist leader, Vice President Odinga, would also end. Simultaneously, the CIA was making appropriate shifts in its operations, throwing its resources into a new kind of vehicle which would embrace the whole Kenyan political mainstream, while isolating the left and setting it up for destruction by Kenyatta. To this end the CIA shifted its emphasis to an organization by the name of "Peace With Freedom."

The CIA programme in Kenya could be summed up as one of selective liberation. The chief beneficiary was Tom Mboya who, in 1953, became general secretary of the Kenya Federation of Labour.”

Both a credible nationalist and an economic conservative, Mboya who was popularly known as ‘TJ’, was ideal for CIA’s purpose. The main nationalist hero and eventual chief of state, Kenyatta, was not considered “sufficiently safe” owing to his initial deep socialist leanings, the dossier said.

Ramparts quotes Mboya as saying:

“Those proven codes of conduct in the African societies, which have over the ages conferred dignity on our people and afforded them security regardless of their station in life.

“I refer to the universal charity, which characterises our societies, and I refer to the African thought processes and cosmological ideas, which regard men, not as a social means, but as an end and entity in society.”

Had the CIA sowed enough seeds of wrath between Mboya and the political establishment in Kenya to provide someone with enough reason to kill him?

Ever since I started this blog, I have always remembered this names Kassim Hanga ,Othman Shriff Who vanish or disappeared. and never seen until today in Zanzibar, Tom Mboya and Robert Ouko was next in Kenya, In Tanganyika Sokoine was one of them ,Oscar Kambona, , Abrahman Babu took refuge in London until they die and Others who were young Leaders during the sixties and 70 inspired me to know more about them and more specifically what happened to them like this in 1969 before I was born.

This powerful quote not only captures Mboya’s own prescription of African socialism, which endeared him to the West and made the CIA view his policy as safe, but it also paints the picture of an articulate, sophisticated and ambitious political thinker.

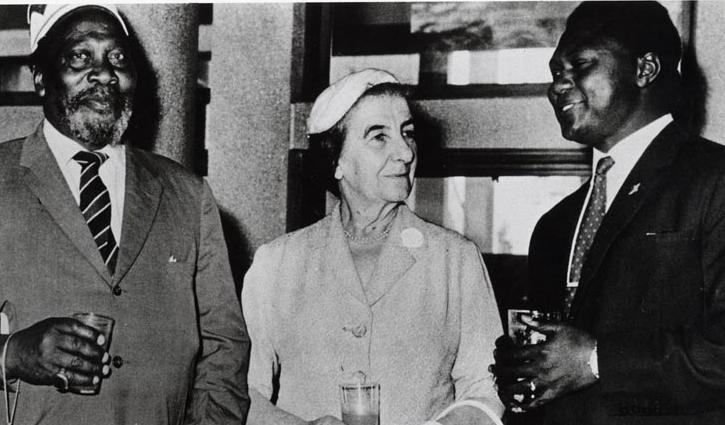

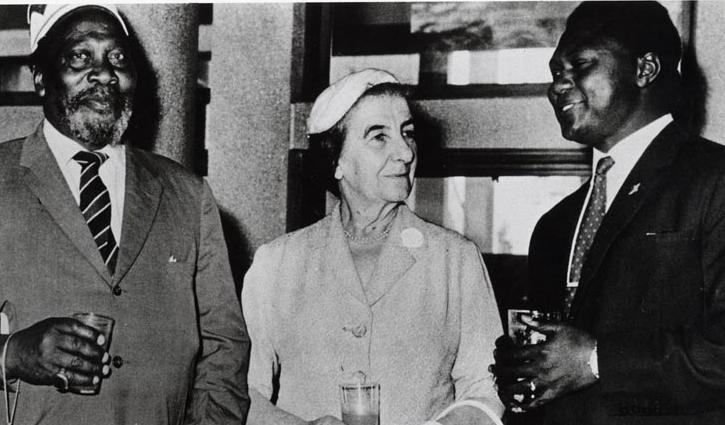

Mzee Jomo Kenyatta, Golda Mier of Israel and Tom Mboya

Soon after, Mboya joined the CIA jet set, travelling around the world from Oxford in the UK to Calcutta in India on funds from such conduits as the Africa Bureau and from the International Confederation of Free Trade Unions (ICFTU).

ICFTU, which played a key role in Kenya’s independence through trade unionism, is an aggregation of international trade union secretariats set up in 1949 to counter an upsurge of left-wing trade unionism outside the communist bloc, according to Ramparts. The CIA allegedly funded operations at the time.

But when George Cabot Lodge, one of the directors of the ICFTU, made the statement (believed to have been in specific reference to Mboya at the time) that “the obscure trade unionist of today may well be the president or prime minister of tomorrow,” he left no doubt about Mboya’s personal ambitions and by extension the CIA’s scheme of things.

Initially, CIA’s natural strategy was to underwrite Mboya and his labour federation as a force against Kenyatta. But when tact changed in accordance with the world order and the CIA’s new priorities, it was agreed that Western labour groups stop funding Mboya.

An accommodation with Kenyatta was now thought necessary, particularly to ensure that he did not support rebels in Congo, and to get him to close ranks against the agitating Kenyan left.

But the die had been cast. The CIA, through its activities, had effectively propped up Mboya as a possible future President of Kenya. That threat was real during Kenyatta’s time and even at the dawn of the second decade of his leadership, according to Ramparts.

It was a strategy that the CIA would use again to the benefit of Kenyatta against Odinga – use the credibility of the appropriate militant to crush the rest. The CIA link, which Mboya vigorously fought to distance himself with, would be used later to fight him politically by branding him a traitor and a man who could not to be trusted. He wrote lengthy responses in his defence.

But had the CIA sowed enough seeds of wrath between Mboya and the political establishment in Kenya to provide someone with enough reason to kill him?

It is the day Tom Mboya was shot dead. there are many questions in East Africa never answered about the deaths of some of this big names I mention above.

He retained the portfolio as Minister for Economic Planning and Development until his death at age 38 when he was gunned down on 5 July 1969 on Government Road (now Moi Avenue), Nairobi CBD after visiting a pharmacy. Nahashon Isaac Njenga Njoroge was convicted for the murder and later hanged. After his arrest, Njoroge asked: "Why don't you go after the big man?. Who he meant by "the big man" was never divulged, but fed conspiracy theories since Mboya was seen as a possible contender for the presidency. The mostly tribal elite around Kenyatta has been blamed for his death, which has never been subject of a judicial inquiry. During Mboya's burial, a mass demonstration against the attendance of President Jomo Kenyatta led to a big skirmish, with two people shot dead. The demonstrators believed that Kenyatta was involved in the death of Mboya, thus eliminating him as a threat to his political career although this is still a disputed matter.

Mboya left a wife and five children. He is buried in a mausoleum located on Rusinga Island which was built in 1970. A street in Nairobi is named after him.

Mboya's role in Kenya's politics and transformation is the subject of increasing interest, especially with the coming into scene of American politician Barack Obama II. Obama's father, Barack Obama, Sr., was a US-educated Kenyan who benefited from Mboya's scholarship programme in the 1960s, and married during his stay there, siring the future Illinois Senator and President. Obama Sr. had seen Mboya shortly before the assassination, and testified at the ensuing trial. Obama Sr. believed he was later targeted in a hit-and-run incident as a result of this testimony

The Tom Mboya Monument above is along the Moi Avenue of Nairobi Kenya. It was honor of Tom Mboya, a Kenyan Minister who was assassinated in 1969.

CIA-Backed African Leader Sponsored the Airlift that Sent Obama's Father to the USA

CIA support for Tom Mboya was terminated well before his muder on July 5, 1969 (sponsored by the CIA?), so no one should come away from this post claiming that Obama's father was in some way Langley's poodle. John Kennedy appears to have restored the financial aid quietly cut off by the Agency. All that these articles establish is CIA financing for Tom Mboya at one time - he was a socialist pawn, not a seditionist jackal - and there is no necessary intelligence connection to Obama's father.

Thomas Joseph Odhiambo Mboya (15 August 1930 – 5 July 1969) was a Kenyan politician during Jomo Kenyatta's government. He was founder of the Nairobi People's Congress Party, a key figure in the formation of the Kenya African National Union (KANU), and the Minister of Economic Planning and Development at the time of his death. Mboya was assassinated on 5 July 1969 in Nairobi. Kenyatta's government. He was founder of the Nairobi People's Congress Party, a key figure in the formation of the Kenya African National Union (KANU), and the Minister of Economic Planning and Development at the time of his death. Mboya was assassinated on 5 July 1969 in Nairobi.

Tom Mboya`s brother and wife Pamela at Mboya`s funeral. Courtesy: http://photography.a24media.com/

It should be noted that the U.S. government and its intelligence agencies have a long history of rogue operations intended to discredit governments or social movements with whom they happen to disagree. To see how far this can go, one need only recall the sordid history of disinformation, lies, and deceit propagated by U.S. government include the assassination of Patrice Lumumba of Congo.

Barack Obama has inspired many a comparison to John F Kennedy ... but the two men forged a less known link - before Obama was even born. The bond began with Kenyan labour leader Tom Mboya, an advocate for African nationalism who helped his country gain independence in 1963.

In the late 1950s, Mboya was seeking support for a scholarship program that would send Kenyan students to US colleges - similar to other exchanges the US backed in developing nations during the Cold War with the Soviet Union. Mboya appealed to the state department. When that trail went cold, he turned to then-senator Kennedy. Kennedy, who chaired the senate subcommittee on Africa, arranged a $100,000 grant through his family's foundation to help Mboya keep the program running.

Fresh details of a conspiracy that could have provided a motive for the assassination of Cabinet Minister Thomas Joseph Mboya have emerged ahead since his death.

The truth is that there were two very well planned phases of the Mboya assassination. That is the actual hit and the cover up that was to follow. Both were carried out clinically. With the clinical precision of a doctor... a surgeon perhaps?

The CIA appears to have recruited the flamboyant minister and former trade unionist in a heavily funded “selective liberation” programme to isolate Kenya’s founding President Jomo Kenyatta, who the American spy agency labelled as “unsafe.”

Tom Mboya and his colleague`s graduating from Howard University in US. Tom was given a honorary Doctorate in Law but he never ever used it in his lifetime. Courtesy: http://photography.a24media.com/

Declassified information in an undated issue of Ramparts, an American political and literary magazine published in the 1960s and early 1970s, accessed by The Standard at the Kenya National Archives, shows an elaborate conspiracy by CIA to prop up Mboya and isolate Kenyatta.

Kennedy: " ... 'Mr Mboya came to see us and asked for help, when none of the other foundations could give it, when the federal government had turned it down quite precisely. We felt something ought to be done.'

"One of the first students airlifted to America was Barack Obama Sr., who married a white Kansas native woman

Mostly my annual memorials have been a lonely crusade. But not this year. Yesterday and today Kenya’s leading daily, The Nation has carried extensive coverage on the assassination of the man I consider to be the greatest politician to ever come out of a Kenyan woman’s womb.

Tom Mboya`s statue at Nairobi, Kenya

I interpret that to mean that finally more and more Kenyans have come to the realization that this assassination was significant and that if the country is to move forward and truly have a new beginning then we must face the ghosts of Tom Mboya and settle this thing once and for all. More so because the chief planner and executor at the centre of that assassination still lives.

Why was Mboya’s assassination so significant? Simply because the two bullets that were fired that Saturday lunch time July 5th 1969 changed the course of Kenya forever. Today we are suffering the consequences of that new course that was clearly charted out that day. Impunity won that day. Years later the rhetorical questions were to be asked over and over again; Mboya was killed and nothing happened, who is so and so? We survived the Mboya assassination what crisis can we not survive?

Tribal politics won that day. In killing Mboya the assassins killed nationalism. To date we are yet to see another Kenyan attracting national popularity in their own right enough to win a presidential poll with votes from every corner of the republic. Every single prominent politician now has their political base in their ancestral village and those who don’t have imported their fellow tribesmates in large numbers into the constituency they represent away form their village. Tom Mboya was a Luo who was time and again voted in by mostly Kikuyus even when other prominent Kikuyus from very prominent families stood against him. To a young Kenyan who understands Kenyan politics today, this statement seems like pure fiction.