HERERO PEOPLE: THE FEARLESS AND WAR-LIKE AFRICAN TRIBE THAT SUFFERED THE WORLD`S FIRST HOLOCAUST AT THE HANDS OF GERMANS

The Herero (meaning "to throw an assegai") people are related to the Bantu people and speak a Bantu language. They live primarily in Namibia and Botswana in southwest Africa and number about 175,000. They are believed to have migrated from the Lake Tanganyika area in the east during the 18th century.

Beautiful herero women in their traditonal outfit

Herero woman 1900,Namibia,Africa

Legend has it that the Herero once left 'a country of many mountains'. They came to a lead wood tree where the two leaders, Kathu, and his brother Nangombe decided to part ways. Kathu trekked north, while Nangombe stayed in Namibia to establish the Herero nation. The word Herero may be derived from okuhera, meaning 'to throw an assegai'. Indeed they were a fearless and warlike nation, taking on the might of the German empire in 1904.

A procession of Hereros dressed in traditional military-style uniforms led by Uetuesapi Mungendje (center) and Keeper of the Holy Fire Chief Tjipene Keja (left). The red accents in the uniforms indicate membership in the Red Flag faction

Location

Approximately 150,000 Herero live in Namibia and about 20,000 in Botswana. The Herero make up approximately 7% of Namibia's population. The Herero have also scattered throughout southern Angola. Oral history has it that the Herero people group left the great lakes region of eastern Africa in the 1500s. They spent the next two centuries migrating to southwestern Africa where they settled in central Namibia. Things were relatively peaceful for the Herero for the next 150 years or so except for the occasional skirmish with the tribes from the south who were pushed north by South Africans who desired their grazing lands. The Herero are herders and the plains of central Namibia are perfect for grazing the cows that are foundational to their culture.

Herero women wearing traditional Victorian-style dresses and headdress shaped after cattle horns. The headdress symbolizes their relationship with cattle farming, which is central to the Herero economy and lifestyle

Culture

Inheritance: The Herero of Namibia and Botswana are unique among southern Africa's indigenous people in that they inherit different things from the mother's and father's families. Residence, religion, and authority are taken from the father's line, while the inheritance of wealth is passed through the mother's clan.

Herero woman

Livelihood: Traditionally, the Herero were nomadic pastoralists. Following contact with Europeans in the mid-19th century, many have become subsistence farmers, growing grains and raising sheep, cattle, and fowl.

A-herero-woman-with-children-in-traditional-clothing

Marriage: Apparently, not much significance is attached to marriage in the Herero group. No personal relationship exists between a man and his wife.

They each keep their own wealth and property. Each man has several wives, although a married woman is not allowed to have additional husbands. Despite the legalities, many women do have relationships with other men.

Dress: The striking Herero women's dress is derived from the Victorian era. German missionaries encouraged the women to wear clothes according to the fashion in Europe at the time. Until the mid 19th century, Herero people like others in southern Africa wore clothing made of leather.

Men and children wore different kinds of leather aprons, and male heroes wore special pieces of animal fur and other ornaments. Adult women wore two leather skirt ieces around their waists, along leather shawl decorated with iron beads and a headdress with three points on top.

Traditional Owambo Herero dress

Like their African neighbours, the Herero began wearing European style clothing in the 1850s, after Europeans missionaries began to settle in southern Africa. Herero people saw rival Nama groups and missionaries wearing western clothing. Today items of Herero clothing are still named after parts of the leather dress, suggesting that Herero people see continuity between the two types of dress codes.

"Herero women and children in traditional costume; Sehitwa, Ngamiland." (Circa1940)

Many children wear leather aprons when they are not in school. Men wear mostly store bought clothes but when they participate in the annual days of Herero cultural celebration they wear military type uniforms and bits of animal fur.

Religion: The Herero believe in a Supreme Being, called Omukuru, the Great One, or Njambi Karunga. Like the Himba they also have a holy, ritual fire which symbolizes life, prosperity and fertility to them. However, the majority have been converted to Christianity, although the Herero church, the Oruuano, combines Christian dogma with ancestor worship and magical practices

Herero woman cooking

Before the Genocide Was Committed on Hereros

Africa is almost certainly the birthplace of the human species. From it the earliest people ventured into Asia and then across the long-vanished land bridge to the Americas, or across the Pacific island chains to Australasia. They also spread to the lands north of the Mediterranean Sea.

Many thousands of years later their European descendants gained glory and wealth by rediscovering the southern hemisphere, and plundering it. They – we – have often treated it, and its inhabitants, with brutality, indifference and contempt. White Europeans forced black Africans to become slaves. White Europeans deprived black people of their homes and communities and cultures.

White Europeans sent their missionaries to change black people’s religion to their own. And in the 19th century white Europeans began moving into Africa to occupy the land as well. The land was desirable for itself: it provided new territory, new possessions and new trade, both for individuals and their countries. The land had other values, too: it provided bases for further take-overs and further military threats; and, above all, it contained riches.

Hereros in their hut before the war

Along the coastline of Namibia runs the Namib desert, a 1,200 mile long strip of unwelcoming sand dunes and barren rock. Behind it is the central mountain plateau, and east of that the Kalahari desert. Namibia’s scarcest commodity is water: this is a country of little rainfall, and the rivers don’t always run. But the very sand of the Skeleton Coast is the dust of gemstones; uranium, tin and tungsten can be mined in the central Namib, and copper in the north; and in the south there are diamonds.

Namibia also has gold, silver, lithium, and natural gas. For most of the region’s history, only metal was of interest to the native tribes. These tribes lived and traded together more or less peacefully, each with their own particular way of living, wherever the land was fertile enough. The San were nomads, hunters and gatherers. The Damara hunted and worked copper. The Ovambo grew crops in the north, where there was more rain, but also worked in metal. The Nama and the Herero were livestock farmers, and they were the two main tribes in the 1840s when the Germans (first missionaries, then settlers, then soldiers) began arriving in South West Africa.

Herero - Near old German mission cemetery in Okahandja - Otjozondjupa Region - 1900

Before the Germans, only a few Europeans had visited it: explorers, traders and sailors. They opened up trade outlets for ivory and cattle; they also brought in firearms, with which they traded for Namib treasures. Later, big guns and European military systems were introduced. The tribes now settled their disputes with lethal violence: corruption of a peaceful culture was under way.

Hendrik Witbooi (sitting on the chair) with fighters of the Nama tribe, ca 1904-1905

During The Berlin Conference of 1888 Germany was awarded South West Africa (what is now called Namibia). The Germans made South West Africa their own colony, and settlers moved in, followed by a military governor who knew little about running a colony and nothing at all about Africa. Major Theodor Leutwein began by playing off the Nama and Herero tribes against each other. More and more white settlers arrived, pushing tribesmen off their cattle-grazing lands with bribes and unreliable deals. The Namib’s diamonds were discovered, attracting yet more incomers with a lust for wealth.

German colonial administrator Theodor Gotthilf Leutwein (seated left) and Herero Supreme Chief Maharero - 1895

Tribal cattle-farmers had other problems, too: a cattle-virus (rinderpest) epidemic in the late 1890s killed much of their livestock. The colonists offered the Herero aid on credit. As a result the farmers amassed large debts, and when they couldn’t pay them off the colonists simply seized what cattle were left. In January 1904, the Herero, desperate to regain their livelihoods, rebelled. Under their leader Samuel Maherero they began to attack the numerous German outposts. Chief Maharero gave very specific instructions that only farmers, traders and soldiers would be attacked. He explicitly stated that missionaries, Britons and Boers were not to be harmed. In most cases, the Herero warriors followed Maharero's instructions to the letter - sparing women, children, missionaries and non-Germans. The Herero cut telegraph wires, destroyed railway lines, stole cattle and overran smaller military stations. Initially about 150 Germans were killed, which provoked colonial outrage. The mere fact the 'savages' had the audacity to challenge white claims of superiority and lands in 'their colony', enhanced racist attitudes which had always been rife amongst the settler population.

Chief Samuel Maherero, the leader of Herero tribe

At the same time, the Nama chief, Hendrik Witbooi, wrote a letter to Theodor Leutwein, telling him what the native Africans thought of their invaders, who had taken their land, deprived them of their rights to pasture their animals on it, used up the scanty water supplies, and imposed alien laws and taxes. His hope was that Leutwein would recognise the injustice and do something about it.

Chief Witbooi of the Namaq Tribe

THE GERMAN COLONIAL WAR OF ANNIHILATION AGAINST THE HERERO NATION

“I, the great general of the German soldiers, send this letter to the Herero people. The Hereros are no longer German subjects. They have murdered and robbed, they have cut off the ears and noses and privy parts of wounded soldiers, and they are now too cowardly to fight. I say to the nation: Any person who delivers one of the Herero captains as a captive to a military post will receive 1,000 Marks. The one who hands over Samuel will receive 5,000 Marks. All Herero must leave the country. If they do not, I will force them with cannons to do so. Within the German frontier every Herero, with or without a gun, with or without cattle, will be shot. I will not take over any more women and children, but I will either drive them back to your people or have them fired on. These are my words to the Herero people. The great General of the Mighty Kaiser, von Trotha.”

On 9 September 2001, the Herero People's Reparations Corporation lodged a claim in a civil court in the US District of Columbia. The claim was directed against the Federal Republic of Germany, in the person of

the German foreign minister, Joschka Fischer, for crimes against humanity, slavery, forced labor, violations of international law, and genocide.

Ninety-seven years earlier, on n January 1904, in a small and dusty town in central Namibia, the first genocide of the twentieth Century began with the eruption of the Herero—German war.' By the time

hostilities ended, the majority of the Herero had been killed, driven off their land, robbed of their cattle, and banished to near-certain death in the sandy wastes of the Omaheke desert.

The survivors, mostly women and children, were incarcerated in concentration camps and put to work as forced laborers (Gewald, 1995; 1999: 141—91). Throughout the twentieth Century, Herero survivors and their descendants have struggled to gain recognition and compensation for the crime committed against them.

Beginning of the German-Herero War

In 1904 Germany began a war of annihilation against the Hereros in retaliation for the Hereros' resistance against the German colonial administration's oppressive treatment. The German-Herero War was one of the world's bloodiest conflicts occurring between 1815 and 1914. From the beginning of the war, many Germans supported the total annihilation of the Hereros.

Two days after the Hereros began resisting the colonial administration, the German Colonial League's Executive Committee released apamphlet calling for a swift and harsh response. A letter written by a German missionary to his colleagues captures the violent sentiment among Germans in Hereroland supporting the annihilation of the Hereros:

"The Germans are consumed with inexpiable hatred and a terrible

thirst for revenge, one might even say they are thirsting for the

blood of the Herero[s]. All you hear these days is "make a clean

sweep, hang them, shoot them to the last man, give no quarter." I

shudder to think what may happen in the months ahead. The

Germans will doubtless exact a grim vengeance."

The diaries, letters, and photographs of contemporaries graphically portray the indiscriminate shootings, hangings, and beatings which were the order of the day. Missionary Elger, stationed in the settlement of

Karibib, described the manner in which Herero prisoners were treated:

Things proceeded in a particularly brutal manner. Herero prisoners were terribly

maltreated, whether they were guüty or not guilty. About 4 Herero were

taken prisoner, because they were supposed to have killed a railway worker

(Lehmann, Habis). The court martial ordered them to be freed and declared

them to be not guilty. However one could not release them as they bore too

many marks of shameful abuse [Schandlicher Misshandlung] on their bodies. For

example, people had beaten an eye out of one. After the court martial had

declared them to be innocent, some of the Germans outside immediately resumed

the abuse with the words, 'the court has declared you to be innocent,

we however want to string you up."

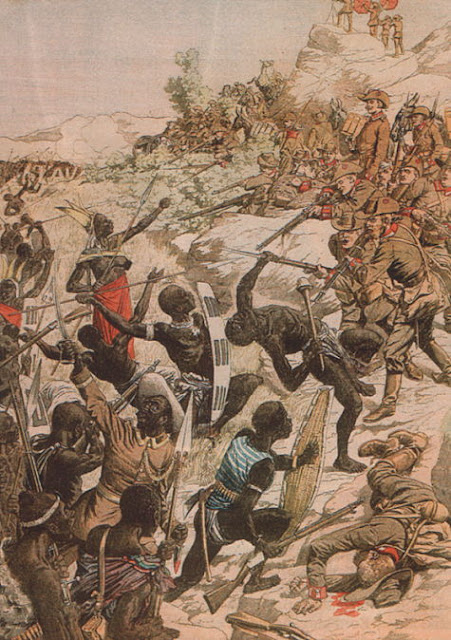

Battle of okahandja on Hereros

Some German politicians did oppose the policy of annihilation. In March 1904 August Bebel, the leader of the Social Democratic Party, objected in the German parliament to German troops' barbarous treatment of

the Hereros. Likewise, Theodor Leutwein, the German governor of South West Africa, criticized the annihilation on economic grounds, arguing that Herero laborers were necessary for the success of the colonial enterprise.

Herero fighters with their weapons

In April 1904, three months after the war began, the German Emperor Wilhelm II appointed Lieutenant-General Lothar von Trotha as commander-in-chief of the German forces in South West Africa. Von Trotha had already become well known for his brutal suppression of indigenous

resistance efforts in the 1896 East African Wahehe Rebellion and the 1900-1901 Boxer Rebellion in China. By November 1904 von Trotha had informed Governor Leutwein that "[h]is Majesty the Emperor only said that he expected me to crush the rebellion by fair means or foul," and that "[i]t was and remains my policy to apply this force by unmitigated terrorism and even cruelty. I shall destroy the rebellious tribes by shedding rivers of blood and money.

Governor Theodore Leutwein with the captain of the namaque (Orlam) Hendrik Witbooi (left) and the leader of the Herero Mahahero Samuel (right)

The Extermination Order

Under the command of von Trotha, the German army sought to engineer a crushing defeat of the Herero in the vicinity of the Waterberg (Pool, 1979: 210—11). In keeping with von Moltke's principles of separate deployment and encirclement, von Trotha sent his armies to annihilate the Herero at the Waterberg. Or, as he put it in his own words:

My initial plan for the Operation, which I always adhered to, was to encircle the

masses of Hereros at Waterberg, and to annihilate these masses with a simultaneous

blow, then to establish various stations to hunt down and disarm the

splinter groups who escaped, later to lay hands on the captains by putting prize

money on their heads and formally to sentence them to death. (von Trotha's

diaries cited in Pool, 1991: 251).

On 11 August, the battle of Hamakari at the Waterberg took place. The Herero were defeated and fled in a southeasterly direction into the dry desert sands of the Kalahari, known to the Herero as the Omaheke. It is estimated that up to 2000 pastoralist Herero escaped eastward in small numbers into the Kalahari desert, into what was then the British protectorate of Bechuanaland (Botswana). Included was Samuel Maharero, the Herero leader. His people arrived with little or no cattle and became subservient to the Tswana - Bechwana chieftain of Sekgathôlê a Letsholathêbê. Von Trotha promptly translated his intention to destroy the Hereros into official policy. On October 2, 1904, von Trotha issued an annihilation order stipulating:

The Herero people must ... leave the land. If the populace does not do this I

will force them with the Groot Rohr [cannon]. Within the German borders

every Herero, with or without a gun, with or without cattle, will be shot. I will

no longer accept women and children, I will drive them back to their people

or I will let them be shot at.

These are my words to the Herero people.

[Signed] The great General of the mighty German Kaiser."

Captured and photographed Herero

A number of authors have sought to deny or at least downplay the existence and implications of Trotha's proclamation, which has become known as the extermination order (Vernkhtungsbefehl) . However, Trotha's

own words, in his diary and elsewhere, indicate that hè understood the implications of his proclamation füll well. On the day the proclamation was issued, Trotha wrote in a letter:

I believe that the nation as such should be annihilated, or, if this was not

possible by tactical measures, have to be expelled from the country by operative

means and further detailed treatment. This will be possible if the water-holes

from Grootfontein to Gobabis are occupied. The constant movement of our

troops will enable us to find the small groups of the nation who have moved

back westwards and destroy them gradually....

My intimate knowledge of many central African tribes (Bantu and others)

has everywhere convinced me of the necessity that the Negro does not respect

treaties but only brute force. (Pool, 1991: 272-4)"

Chained hereros

An official report sent two days later by von Trotha to the chief of the army general staff underlined the intent of the extermination order:

'The crucial question for me was how to bring the war against the

Herero [Nation] to a close.... As I see it, the nation must be

destroyed as such .... I ordered the warriors... to be

court-marshalled and hanged and all women and children who

sought shelter here to be driven back into the sandveld [the

Kalahari Desert] .... To accept women and children who are for

the most part sick, poses a grave risk to the force, and to feed them

is out of the question. For this reason, I deem it wiser for the entire

nation to perish .... This uprising is and remains the beginning of

a racial struggle . . ."

Boys in chains

The day after the Germans announced the extermination order, they forced thirty Herero prisoners, including women and children, to watch the hanging of the Hereros who had been sentenced to death.' The German officials read the extermination order to the prisoners, handed out printed

copies, and drove them into the Kalahari Desert." The hangings marked the beginning of the German efforts, led by von Trotha, to destroy the Hereros.

Von Trotha's correspondence confirms that the German-Herero War was a war of annihilation expressly intended to wipe out the Hereros. In a letter to Governor Leutwein on October 27, 1904, he wrote, "That [Herero] nation must vanish from the face of the earth.'' Governor Leutwein responded to this letter by requesting permission from the German Foreign Office to allow the Hereros to surrender, writing that "[a]ccording to reliable sources, a number of Herero[s] have offered to submit." The writings of von Trotha's subordinate officers in Hereroland also provide evidence of von Trotha's intent to annihilate the Hereros.

General Lothar von Trotha (front right) and Governor Theodor Leutwein (front left) with officers in Windhoek (German Southwest Africa), 1904

In November 1904 the Foreign Office recalled Leutwein to Germany, and Lothar von Trotha replaced him as governor of South West Africa. Although Leutwein's recall quieted his criticism of von Trotha's tactics, opposition to von Trotha's extermination policy increased. Missionaries, members of the Colonial Department, and others criticized von Trotha's plan. Imperial Chancellor Bernhard von Billow wrote to Emperor Wilhelm II requesting permission to revoke von Trotha's Extermination

Order.

The request stated four reasons: (1) inconsistency of the plan to annihilate the Hereros with Christianity and humanity, (2) impossibility of success, (3) economic detriment to the colonial enterprise by depriving it of its "productive forces," and (4) establishment of a policy that was "demeaning to [Germany's] standing among the civilized nations of the world."

I followed their spoor and found numerous wells which presented a terrifying

sight. Cattle which had died of thirst lay scattered around the wells. These cattle

had reached the wells but there had not been enough time to water them. The

Herero fled ahead of us into the Sandveld. Again and again this terrible scène

kept repeating itself. With fevernt energy the men had worked at opening the

wells; however the water became ever sparser, and wells ever more rare. They

fled from one well to the next and lost virtually all their cattle and a large

number of their people. The people shrank into small remnants who continually fall

into our hands [unsere Gewalt kamen]; sections of the people escaped now and

later through the Sandveld into English territory [present-day Botswana]. It was a

policy as gruesome as it was senseless, to hammer the people so much; we could

have still saved many of them and their rieh herds, if we had pardoned and taken

them up again; they had been punished enough. I suggested this to General von Trotha,

but he wanted their total extermination. (von Estorff, 1979: 117; author's translation)

On December 8, 1904, the Emperor rescinded the Extermination Order. However, the decision was narrowly tailored and did not prohibit future genocidal acts. Instead it only required that "mercy" be included among the colonial administration's possible policy options. The general' staff wrote, "His Majesty has not forbidden you to fire on the Herero[s].... But the possibility of showing mercy, ruled out by the proclamation of 2 October [the Extermination Order], is ... to be restored again. In addition, the rescission of the Order did not officially disapprove of von Trotha or his tactics. Indeed, the following year Emperor Wilhelm II awarded von Trotha a medal of honor for his work in South West Africa.

By late 1905, an estimated 8,800 Herero were confined in camps, working on various military and civilian projects scattered across German South West Africa (Berichte der Rheinischen Missions-Gesellschafi, 1906: 10). Missionary sources provide us with eyewitness accounts of conditions in the camps.

Missionaries stationed in the Herero Konzentrationslager reported to their superiors in Germany on the extensive and unchecked rape, beatings and execution of surrendered Herero by German soldiers (Gewald, 1999: 184-204). Missionary Kuhlmann spoke of the delight of settler women witnessing the drawn-out public hangings of captured Herero in Windhoek. At one such hanging, a drooling Herero fighting for his life was berated: 'You swine, wipe your muzzle' (Oermann, 1998: 113—14). In Karibib,

missionary Elger wrote:

And then the scattered Herero returned from the Sandfeld. Everywhere they

popped up — not in their original areas - to submit themselves as prisoners.

What did the wretched people look like?! Some of them had been starved to

skeletons with hollow eyes, powerless and hopeless, afflicted by serious diseases,

particularly with dysentery. In the settlements they were placed in big kraals,

and there they lay, without blankets and some without clothing, in the tropical

ram on the marsh-like ground. Here death reaped a harvest! Those who had

some semblance of energy naturally had to work—

It was a terrible misery with the people; they died in droves. Once 24 came

together, some of them carried. In the next hour one died, in the evening the

second, in the first week a total of ten - all [lost] to dysentery - the people had

lost all their energy and all their will to live

Hardly cheering cases were those where people were handed in to be healed

from the effects of extreme mistreatment [schwerer Misshandlungen]: there were

bad cases amongst these."

Slave Labor and Concentration Camps

This Deutsch Süd-Wes Afrika trading card was made by the German chocolate maker Hartwig & Vogel, Dresden. It specifically named and included a "Hottentot Hut" with "Herero Mother and Child" placed to the front of the "Windhoek Castle". Compare the scene to the reality of the "Windhoek Castle" with the German concentration death camp shown to the card upper right.

*The Namas who supported the Hereros cause were also not spared at all. The Nama led by Hendrick Witbooi, had fought with the Germans against the Herero. Regardless, von Trotha turned his murderous attention to him, sending Witbooi, Cornelius Fredericks and other chiefs the following message; The Nama who choose not to surrender and lets himself be seen in the German area will be shot until all are exterminated. Those who at the start of the rebellion committed murder against whites, or have commanded that whites be murdered have by law, forfeited their lives. As for the few not defeated, it will fare with them as it fared with the Herero, who in their blindness also believed that they could make successful war against the powerful German Emperor and the great German people. I ask you, where are the Herero today? Approximately ten thousand Nama were annihilated during the ensuing battles while 9000 were confined to concentration camps.

Hendrik Witbooi (Center)

Hendrik Witbooi was killed. In September 1906, Cornelius Fredericks and the fighters of Witbooi surrendered and were sent to Shark Island. Death in the camp was meticulously recorded. Solders were tasked with naming the dead and recording numbers. Their records show that of the 1795 Nama prisoners who had arrived, only 763 were alive in April. One thousand thirty two had died. The detailed record shows that of the living, 123 were in such poor health they would soon die. By 1908 when the camps were closed, disease and malnutrition had killed up to 80% of all prisoners who had entered Shark Island - including Namaqua chief Cornelius Fredericks. (Hendrick Witbooi had been killed in battle.)*

Shark Island Death Camp

Captured and chained Herero/namas

Even after the Emperor rescinded the Extermination Order, the German colonial administration continued to decimate the Hereros by forcing Herero prisoners of war into slave-labor and concentration camps. The German Imperial Chancellor, Prince von Bilow, ordered the creation

of concentration camps in Hereroland in 1904." By late May 1905 the Germans had taken 8,040 Herero prisoners of war, of whom more than three-quarters were women and children." The Germans immediately shipped the prisoners to slave-labor camps, where they worked under grueling conditions

' and were subjected to medical experiments.' According to one account, conditions within the camps were brutal: "[Prisoners of war] were placed behind double rows of barbed wire fencing.... and housed in pathetic [jammerlichen] structures constructed out of simple sacking and planks, in such a manner that in one structure 30 to 50 people were forced to stay without distinction as to age and sex. From early morning until late at night, on weekdays as well as on Sundays and holidays, they had to work under the clubs of raw overseers... until they broke down.... Like cattle, hundreds were driven to death and like cattle they were buried. In Windhoek, the capital of the territory, a separate camp was created in which Herero women were kept specifically for the sexual gratification of German troops.

Anthropologist Wilhelm Waldeyer received Herero body parts from the concentration camps. They were shipped to Berlin by doctors Dansauer, Jungels, Mayer and Zöllner, then studied by him and his students.

The zoologist Leonard Schultze complained of the difficulty collecting animal specimens in the wild because of the fighting. However, he noted the fighting presented opportunities for 'physical anthropology'. He said; 'I could make use of the victims of the war and take parts from fresh native corpses, which made a welcome addition to the study of the living body. Imprisoned Hottentots were often available to me'.

Herero/nama heads used for experiment by the Germans

("[Clamp prisoners were transformed into human subjects for various laboratory experiments designed to confirm the racial inferiority of black peoples. These experiments were overseen by Dr. Eugen Fischer who became the senior geneticist of the Nazi regime.").[M]edical experiments were also conducted there by (literally) the teachers of Josef Mengele, the Auschwitz "Angel of Death" [forty] years later."). He studied and made tests with the heads of 778 Herero and Nama dead prisoners of war. Severed heads were preserved - numbered and labeled as Hottentotte - the German colonial name for the Nama. He used 'research' to prove the black race is inferior to the Germanic - Aryan race. By measuring skulls - facial features and eye colors - Fischer and his protégés sought to prove the native races were inferior - and as he put it - animals. Fischer's work influenced Nazi physicians and German medical experiments in concentration camps. Fischer's book on his research in Namibia, The Principles of Human Heredity and Race Hygiene, "went on to become one of Hitler's favorite reads." He later became chancellor of the University of Berlin, and one of his prominent students was Josef Mengele, "the notorious doctor who performed genetic experiments on Jewish children at the Auschwitz concentration camp." ("Here [in German South West Africa] the first concentration camps were set up, and 30 years before Hitler the cult of the German master race was practiced." "Concentration camps were neither a Russian invention nor a German one. They were first established in 1896 by Spaniards in Cuba .. The German colonial powers... contributed to the history of the concentration camp by introducing the idea of forced labor "

.The mortality rate was extremely high: more than 12% of the Hereros serving as slave labor for railroad construction died in a period of six weeks

. Sexual serfdom: Two adolescent Herero girls posing naked were photographed by a German soldier. PHOTOGRAPH: COURTESY OF JUTTA ANA DOBLER

In the settlement of Windhoek, missionary Meier described the condition of Herero who came to the sickbay run by the mission. His words provide some idea of what occurred in the Windhoek camp:

How often these poorest, those who deserved pity, came staggering! Many of

them, who could no longer move, were brought on stretchers, most of them

unconscious; however, those who could still think were glad that the hard

supervision of the ... guards in the Kraal and their Shambok [rawhide whip] ...

had for the time being been left behind'.

The Germans killed all Hereros who tried to escape the inhuman conditions in the camps immediately and without mercy. The brutal living and working conditions in the camps constituted a policy decision on the part of Germany. Vice Governor Hans Tecklenburg commented on the high mortality rate in the camps in a letter to the Colonial Department stating, "[t]he more the Herero people experience personally the consequences of the rebellion, the less will be their desire-and that of generations to come-to stage another uprising.... [T]he ordeal they are now undergoing is bound to have a

more lasting effect.

Felix von Luschan, director of the Ethnology Museum in Berlin, was an ethnologist obsessed with collecting human skulls and skeletons. He drew up guidelines for travelers to German colonies, instructing them how to pack skulls, skeletons and human brains for shipment. This 'currently respected director' boasted, you could get a human skeleton for a piece of soap.

One year after the extermination war began, Felix Luschan asked a notorious racist by the name of Lieutenant Ralf Zürn 'commander of Okahandja', if he was aware of any way in which the Museum might collect a larger number Herero skulls? The Lieutenant had already supplied him with a skull, wrote back saying this would be possible 'since in the concentration camps taking and preserving the skulls of Herero prisoners of war will be more readily possible than in the country, where there is always a danger of offending the ritual feelings of the natives'.

Soldiers began to trade in the skulls of dead Herero and Nama people. They sold them to scientists, museums and universities back in Germany who advertized for them. The practice was so widespread that this postcard was made showing soldiers packing skulls - as normal colonial life.

The brutality against the Hereros continued as Friedrich von Lindequist succeeded von Trotha as governor of South West Africa.Under von Lindequist, German military hostilities ceased briefly from

December 1905 until mid-1906. Despite the pause in military strikes, von Lindequist established concentration camps in December 1905 for Hereros who had surrendered to Germans. By May 1906, the Germans had captured 14,769 Hereros: 4,137 men, 5,989 women, and 4,643 children.Two months later, von Lindequist wrote to the Colonial Department that "[t]he northern and central parts of the country, in particular Hereroland proper, are virtually devoid of Herero[s].... Those still roaming about will consider themselves lucky if they come to no harm.

Starved Hereros who survived their escape through the arid desert of Omaheke.

The German's annihilation campaign was brutal and successful. When the Germans did not shoot or hang Herero prisoners of war, they drove them into the desert. The Germans tattooed survivors "GH, Gefangene Herero (imprisoned Herero[s])" and forced them into slave-labor and concentration camps. " By the end of the war in 1907, "the Herero people as such was annihilated."

German soldiers hanging Heroro and namas

Shootings,three German soldiers shoot against a tied African

In just a few years, the Germans killed more than 65,000 of the 80,000 Hereros: they slaughtered them in battle, poisoned them, tortured them to death, trapped them in their huts and burned them to death, and drove them into the Kalahari Desert to die of hunger and thirst. As the following Part illustrates, Germany's massacre of the Hereros differs from many other atrocities perpetrated by European colonizers against indigenous Africans because its express purpose was annihilation.

The Herero camps were formally abolished in 1908.Thereafter, the Herero were confined within a tangled web of legislation that sought to control every aspect of the lives of all black people living in German South West.

Africa (GSWA). Within the areas of German control, all Africans over the age of 8 were ordered to wear metal passes. These passes, which were embossed with imperial crown, magisterial district, and labor number, were used to facilitate German control of labor. In addition, Herero were prohibited from owning land and cattle, the two foundations of what had been a society based on pastoralism.

herero in chains

The 'Blue Book'

At the outbreak of the First World War, South African forces under British command invaded GSWA and successfully defeated the much-vaunted German army. As the war progressed, it became clear that the victorious parties had no intention of allowing Germany to retain its colonies. To this end, from at least 1915 onwards British colonial officials were instructed to gather materials which would strengthen the British Empires claims to Germany's colonies.

In Namibia, this task was made much easier by the existence of an extremely well-organized and detailed government archive which awaited the incoming military administration in Windhoek. It contained chillingly detailed accounts and reports on the manner in which GSWA settlers, and the colony's administration, had dealt with the country's original inhabitants. Apart from files dealing with the incarceration of Herero in concentration camps and their distribution among settlers and private companies, the archives also contained a series of files on the excesses of settlers who had flogged Herero and Nama workers. Glass-plate negatives detailed the torn and rotting backs of women flogged for alleged insubordination, and pages upon pages of court transcripts detailed the brutal lashing of laborers.

The combination of dry testimony taken from the German archives in Windhoek, along with a series of painstakingly detailed statements given under oath by surviving Namibians, formed the basis of one of the most shocking documents of colonial history. The Report on the Natives of SouthWest Africa and their Treatment by Germany (London, 1918), generally referred to as the 'Blue Book,' remains an indispensable source document on the nature of German colonial rule in Namibia. It is beyond question thatthese materials effectively scuttled any attempts by Germany to retain control over its former colonies, and Namibia in particular. In Article 119 of the Versailles Treaty, Germany was declared unfit to govern colonies,

and was forced to renounce 'in favor of the Principal Allied and Associated Powers all her rights and titles over her oversea possessions.' In addition, under Article 22 of the new League of Nations charter, Namibia was held to be 'inhabited by peoples not yet able to stand by themselves under the strenuous conditions of the modern world,' and thus was deemed a territory that could 'be best administered under the laws of the Mandatory [the Union of South Africa] as integral portions of its territory.' Accordingly, Namibia was placed under the jurisdiction of South Africa (see du Pisani, 1985: 76).

Though the 'Blue Book' is one of the primary documents detailing the injustices perpetrated against the Herero and Nama peoples of Namibia, it was not used to ensure that Herero would receive compensation. Instead, the 'Blue Book' served to ensure that Namibian territory would be granted to South Africa to administer as a mandated territory. Far from the Herero receiving their land back, the new South African administration forced them to settle on marginal lands in reserves established on the fringes of the Omaheke, the desert into which they had been driven in the past.The new South African administration continued the policies initiated by its German predecessor. The lands previously occupied by the Herero

continued to be reserved for white settlement, and in the years after World War I the South African administration pursued an aggressive policy of land settlement for white Afrikaans-speaking immigrants from Angola and South Africa. In short, the injustices described with stark clarity in the 'Blue Book' were dismissed in the interests of white settler unity.

White settler unity and the 'Blue Book'

Nonetheless, the existence of the 'Blue Book' came to bedevil settler politics under the South African mandate. German settlers called for the "Blue Book' to be banned and all extant copies destroyed. In 1925, the first all-white election for a legislative assembly took place. Representatives of the German settler party, the Deutsche Bund in Südwestafrika, opposed settler parties allied to the Union of South Africa. Anxious to

maintain a working relationship with the settler bloc in the legislative assembly, the South African administrator, A.J. Werth, acceded to settler demands for the abolition of the 'Blue Book.' Thus, in 1926, one Mr Strauch, a member of the legislative assembly, tabled a motion stating that the 'Blue Book' 'only has the meaning of a war-instrument and that the time has come to put this instrument out of Operation and to impound and destroy all copies of this Blue Book, which may be found in the official records and in public libraries of this Territory.'

The motion passed, and legislation came into effect in all territories administered by the Union of South Africa banning distribution of the 'Blue Book.' Copies were no longer made available to the public, were

removed from libraries, and were destroyed. In the rest of the British Empire, copies of the 'Blue Book' were transferred to the Foreign Office. Even in wartime Britain as late as 1941, in response to a request from the

Ministry of Information, it was noted that 'no copy may be issued without authority of the librarian.' Strauch, and his fellow members of the Deutscher Bund, consciously used the Herero genocide — or rather the recorded role of German settlers and soldiers in it - to put pressure on the South African administration. As Strauch noted, passing the motion hè had proposed 'would... remove one of the most serious obstacles to mutual trust and cooperation in this country [Namibia].' In his view,'the honour of Germany had been attacked in the most public manner and it was right that the attack should be repudiated in an equally public fashion.... The defence of the honour of ones country was a solemn duty imposed upon all sons of that country.' The validity of Strauchs claims went unquestioned by the assembly, and certainly no Herero view of the events was allowed an airing. The subjective arguments of Strauch and his compatriots thus sought to obscure the past in the interest of preserving their own privileged position as settlers. The promise of peaceful cooperation with the German settler Community was uppermost in the minds of South Africa's

administrators. Strauchs claim that 'the Germans were ready and anxious to cooperate in the building up of South West but they could not do so.

Seeking to deny the past

In the run-up to Namibian independence in 1990, Brigitte Lau, a historian well known for her uncompromising stand against South African colonial rule in Namibia, published an article that shocked and surprised many of her colleagues. In her article, she stated: There is absolutely no evidence... that the Herero perished or were used on a large scale as "slave laborers"' (Lau, 1989: 5). Furthermore, Lau argued that the Vernichtungsbefehl issued by General Lothar vonTrotha, commanding officer of German forces in Namibia at the time, 'was a successful attempt at psychological warfare never followed in deed' (Lau, 1989: 5).

Lieutenant von Durling - German Death Camp at Shark Island

In addition, Lau sought to problematize the term Vernichtung by arguing that it did not imply extermination.

Finally, she argued that the basis for much of the allegations of genocide by German soldiers in Namibia, the 1904 'Report of the Treatment of Natives by Germany' (sic), was 'an English piece of war propaganda

with no credibility whatsoever' (Lau, 1989: s). Needless to say, Lau's article exploded like a bombshell among the small Community of scholars specializing in Namibian history (Lau, 1989: 4—8).

Hereros in Shark Island German Death (Concentration) Camp

With hindsight, and on the basis of later conversations, it became clear that Lau wished to move the academie community away from what she saw as its unjust fascination with the Herero—German war. Instead, she argued, historians should concentrate on what she considered to be the more destructive colonial rule of South Africa in Namibia. Yet again, the genocide that Imperial Germany perpretrated upon the Herero was being negated and denied in the interests of contemporary politics.

Nevertheless, Lau's article, recently republished in German, continues to have repercussions that extend far beyond Namibian history. On the electronic website of the Traditionsverband ehemaliger Schutz und Uberseetruppen (Traditional association of the former protectorate and overseas forces), an organization that seeks to preserve and glorify the memory of Germany's colonial armies, Laus article is predictablyacclaimed. In addition, the Traditionsverband directs readers to 'Wiedergutmachung am der Volk der Herero?' (Restitution for the Herero People?), an article that denies von Trotha harboured any genocidal intentions, and seeks to dismiss Herero claims for reparation.

Hanged Hereros

Hanged Hereros

Michael Scott and Herero representations to the UN

To the members of the white settler community, it may have looked as if the attempt to destroy and rewrite the past according to their own preferences had succeeded. For a number of years after 1926, nothing was

heard of the Herero genocide. Within the territory, Herero had been forced to withdraw to the newly established Native reserves, where they refrained from directly articulating demands that related to the genocide (Gewald, 2OOi).This is not to say that the genocide was no longer of any importance to Herero society - far front it. Instead, Herero society turned in upon itself, seeking äs far äs possible to refrain from any interaction with the colonial state. References to the genocide perpetrated against the Herero surfaced from time to time in unexpected places, yet the subject was no longer part and parcel of the colonial discourse.

In the aftermath of World War II, the South African government undertook steps to incorporate Namibia as the fifth province of the Union ofSouth Africa. To this end, in 1946 a series of carefully structured meetings

were held with the African population of the territory. As the newly formed United Nations had taken over from the League of Nations, Namibia, as a mandated territory, feil again under South African jurisdiction, with UN oversight. It was widely hoped that the colonially appointed and recognized leaders of Namibias African populations would give their sanction to South Africa's plan to incorporate Namibia. However, this was not to be. The events of 1904—08 again became central to the concerns of settlers and the colonial administration with the arrival of the Rev. Michael Scott in Windhoek in 1947. In conjunction with

Herero leaders, Scott used the atrocities perpetrated in the Herero genocide as a weapon against the incorporation of Namibia into South Africa. In the immediate aftermath of the Holocaust, the füll extent of which was still only just beginning to be understood, an earlier genocide inflicted by the fathers of the Nazi perpetrators made for powerful political ammunition (Emmett, 1999: 253).

Throughout most of 1948, Michael Scott lived in a tent along the Gammans river, just beyond the old location of Windhoek. Here hè met and entertained township residents, many of whom had experienced the

horrors of German rule firsthand (Troup, 1950: 173—80). Scott could not fail to have his attention drawn to the Herero genocide. Here, in a nutshell, Scott held, were the core inequities of colonial rule: a people had been driven off their land, slaughtered, banished to live in barren homelands — and still they held no rights. This concise presentation of history served to detail the injustice suffered by the Herero, at the hands not only of Imperial Germany, but of the mandated power, South Africa.

surrounded Herero

An article entitled 'Michael Scott and the Hereros,' published in The New Statesman and Nation in 1949, aptly summarized Scotts view of Namibian history:

"Then came the German colonists, hungry for land; and finally von Trotha, a

genera! whom Hitler would have delighted to honour.... In 1904 hè issued the

'Extermination Order.' All Hereros whether man, woman or child were to be

killed. An orgy of looting, torture, and massacre followed. To read the records

is exactly like reading the accounts of the obliteration of Poland, except that the

Germans had not gas chambers then, but killed babies with their own hands,

or burned sick old women in their huts. The tribe broke and fled The

majority, all but fifteen thousand out of ninety thousand, were hacked to pieces

by the Germans or died of thirst.'

The mention of von Trotha s 'extermination order' clearly indicates that Scott had managed to gain access to a copy of the 'Blue Book.' Scott's history also made explicit the link between the horrors perpetrated by the

Nazis and the activities of Imperial Germany's forces in Namibia, a link that continues to generate considerable academic interest. In addition, Scott explored how the South Africans had betrayed the Herero:

In the 1914 war, lured by British promises that native lands would be returned,

the desert remnant trekked back. But in 1918 they met not the British as the

Mandatory Power, but the South Africans, who never for a moment considered

giving them back their tribal lands. Some pastures were left to the German

settlers who remained. More went to the Afrikaner settlers.

Throughout 1948 and 1949, in the face of constant harassment, Scott sought to bring conditions in Namibia to the attention of the world. Eventually, in November 1949, the United Nations granted Scott an official

hearing. Clearly, this did not stand him in good stead with South African officialdom. In the months following Scott's hearing, a campaign was initiated by the colonial authorities in Namibia, seeking to cast aspersions

on Scott's statements. Vihfied in the press, Scott continued to be supported by Herero, many of whom recalled the events of 1904-08 to justify their faith in the reverend. One such Herero, who signed his letter 'A

Native who has been deprived of his land from 1904—1950,' noted: 'I want to emphasise that the Information given by the Rev. Michael Scott at UNO is what actually happened in S.WA. and was obtained from the best reliable sources' (Windhoek Advertiser, 1950). Shortly after, Scott, already the victim of constant harassment, was declared a prohibited immigrant and prevented from ever returning to Namibia.

Regaining the international stage

It is in the context of the above events that on 22 August 1999, Dr Kuaima Riaruako, the self-appointed paramount chief and king of all of the Herero, proclaimed that the 'Herero nation' as a whole had decided

to approach the International Court of Justice (ICJ) in The Hague in order to lay a charge of genocide against the German state, calling for reparations for the slaughter and other atrocities inflicted on the Herero.

At the time, Riaruako s statement ruffled a few feathers in Namibia itself. German diplomats in Windhoek emailed colleagues in Bonn/Berlin to look into the issue. Two days later, a clinically worded statement by a

spokesperson of the World Court put everyone, with the exception of Riaruako, at ease: 'Only states may be parties in contentious cases before the ICJ and hence submit cases to it against other states.'

In the absence of a formal apology, the call for war reparations from the Federal Republic of Germany has become more vociferous. Government inaction, the continued extensive presence of German tourists, settlers, businesses and farms, and continued marginalization of the Herero lend increasing legitimacy to the Herero claims. This new visibility was evident with the launch of two court cases in the US District of Columbia. With the support of Afro-American organizations, the 'Herero People's Reparations Corporation' (HPRC) was established as a corporation, in keeping with the laws of the District of Columbia, and the court cases were launched in its name. Three German companies, Deutsche Bank AG, Terex Corporation (Orenstein und Koppel), and Woermann Line (Deutsch Afrika Linien), •were charged, along with the Federal Republic of Germany (in the person of its foreign minister, Joschka Fischer). The introductory paragraph of the charge reads as follows:

the Federal Republic of Germany ('Defendant' or 'Germany'), in a brutal alliance with German multi-national corporations, relentlessly pursued the enslavement and the genocidal destruction of the Herero Tribe in Southwest Africa, now Namibia. Foreshadowing with chilling precision the irredeemable horror of the European Holocaust only decades later, the Defendant formed a German commercial enterprise which cold-bloodedly employed explicitly sanctioned extermination, the destruction of tribal culture and social organization, concentration camps, forced labor, medical experimentation and the exploitation of women and children in order to advance their common financial interests.

The Federal Republic of Germany, as the legal successor to Imperial Germany, is responsible for what happened in the name of the Kaiser in Namibia. Genocide was perpetrated; thousands of people were put to

work as forced laborers; thousands were subjected to all manner of abuse. People were robbed of their land, possessions, and livestock, and driven forever from their ancestral lands. It is hard to say what form recompense in this egregious case should take; but a simple apology would be a beginning.

Over sixty years ago Germany began a process and acceptance and apology for the Holocaust in the second world war. Fifteen years before Hitler joined the Nazi Party, Germany killed 1000's in the African death camps of the Kaisers army. This fact makes a myth out of the post war foundation Germany it was supposedly built on. Make no mistake - the ghosts of the Herero and Nama will not go away. of Germanic input made NO dent on 21st century Herero and Nama graves. These continue to reflect the foundations of Herero and Nama pastoral culture, which von Trotha - Fischer and the Kaiser intended to annihilate.

The calls by the Namibian Hereros for reparation and court action has not yielded ant fruitful dividends from the German authorities that caused great inhumane treatment to the Namibian Hereros. A recent delegation of Namibians Herero leaders to Germany for the skull of hereros that were sent to Germany for experimentation were ill-treated by their German hosts. They were left in the meeting by their german counter-parts whiles the Herero delegations were still talking. Germany has made it abundantly clear that the development aid they have been given to Namibia since independence is for the benefit of all Namibians including Hereros and Namas that suffered under their repressive colonial era.

The German continue to deny the inhuman treatment/genocide committed against the Hereros. However, expressed regret for the incident. A statement issued by German Deputy Foreign Minister, Cornelia Pieper last month read, "We Germans acknowledge and accept this heavy legacy and the ensuing moral and historical responsibility to Namibia.

"The German Government is fulfilling this duty through particularly close bilateral cooperation - and development cooperation - with Namibia," it continued.

Pieper added, "I would also like to express my own personal deep regret and shame for what was done to the ancestors of the tribal representatives now in Berlin."

For his part, the CEO of Charite University Hospital, Professor Karl Max Einhaupl, apologized to the Namibian delegation present at the ceremony in Berlin for the role played by German scientists.

"With this step we face up to an inglorious chapter of German history," he said. "As a medical doctor and scientist myself, it is especially painful for me to realize that even physicians worked in the service of this early form of racism."

Peter said historians now agree that much of the research undertaken by these early scientists was a precursor to Nazi ideology and is now universally acknowledged as a "perverse" science.

Descendants of the von Trotha family travelled to Omaruru Namibia at the invitation of Herero Supreme Chief Alfons Maharero in 2007, whose grandfather Samuel Maharero led the Herero uprising in 1904. The von Trotha family publicly apologized for Lothar von Trotha's brutal cruelty to this people. Wolf-Thilo von Trotha said; "We, the von Trotha family, are deeply ashamed of the terrible events that took place 100 years ago". Well they should be! So too should be countless generations of von Trotha's to come... Imagine that one hundred years before their visit, and undisclosed German soldier was reported to have said of the massacres;

(http://scholars.law.unlv.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1299&context=facpub)

(https://openaccess.leidenuniv.nl/bitstream/handle/1887/4853/ASC-1293873-001.pdf?sequence=1)

http://www.ezakwantu.com/Gallery%20Herero%20and%20Namaqua%20Genocide.htm

This skull along with 19 others were brought to Berlin by German soldiers after the Herero and Namaqua Genocide that occured between 1904 and 1907.

"We have come to first and foremost to receive the mortal human remains of our forefathers and mothers and to return them to the land of their ancestors," delegation member Ueriuka Festus Tjikuua told reporters in Berlin.

Beautiful herero women in their traditonal outfit

Herero woman 1900,Namibia,Africa

Legend has it that the Herero once left 'a country of many mountains'. They came to a lead wood tree where the two leaders, Kathu, and his brother Nangombe decided to part ways. Kathu trekked north, while Nangombe stayed in Namibia to establish the Herero nation. The word Herero may be derived from okuhera, meaning 'to throw an assegai'. Indeed they were a fearless and warlike nation, taking on the might of the German empire in 1904.

A procession of Hereros dressed in traditional military-style uniforms led by Uetuesapi Mungendje (center) and Keeper of the Holy Fire Chief Tjipene Keja (left). The red accents in the uniforms indicate membership in the Red Flag faction

Location

Approximately 150,000 Herero live in Namibia and about 20,000 in Botswana. The Herero make up approximately 7% of Namibia's population. The Herero have also scattered throughout southern Angola. Oral history has it that the Herero people group left the great lakes region of eastern Africa in the 1500s. They spent the next two centuries migrating to southwestern Africa where they settled in central Namibia. Things were relatively peaceful for the Herero for the next 150 years or so except for the occasional skirmish with the tribes from the south who were pushed north by South Africans who desired their grazing lands. The Herero are herders and the plains of central Namibia are perfect for grazing the cows that are foundational to their culture.

Herero women wearing traditional Victorian-style dresses and headdress shaped after cattle horns. The headdress symbolizes their relationship with cattle farming, which is central to the Herero economy and lifestyle

Culture

Inheritance: The Herero of Namibia and Botswana are unique among southern Africa's indigenous people in that they inherit different things from the mother's and father's families. Residence, religion, and authority are taken from the father's line, while the inheritance of wealth is passed through the mother's clan.

Herero woman

Livelihood: Traditionally, the Herero were nomadic pastoralists. Following contact with Europeans in the mid-19th century, many have become subsistence farmers, growing grains and raising sheep, cattle, and fowl.

A-herero-woman-with-children-in-traditional-clothing

Marriage: Apparently, not much significance is attached to marriage in the Herero group. No personal relationship exists between a man and his wife.

They each keep their own wealth and property. Each man has several wives, although a married woman is not allowed to have additional husbands. Despite the legalities, many women do have relationships with other men.

Dress: The striking Herero women's dress is derived from the Victorian era. German missionaries encouraged the women to wear clothes according to the fashion in Europe at the time. Until the mid 19th century, Herero people like others in southern Africa wore clothing made of leather.

Men and children wore different kinds of leather aprons, and male heroes wore special pieces of animal fur and other ornaments. Adult women wore two leather skirt ieces around their waists, along leather shawl decorated with iron beads and a headdress with three points on top.

Traditional Owambo Herero dress

Like their African neighbours, the Herero began wearing European style clothing in the 1850s, after Europeans missionaries began to settle in southern Africa. Herero people saw rival Nama groups and missionaries wearing western clothing. Today items of Herero clothing are still named after parts of the leather dress, suggesting that Herero people see continuity between the two types of dress codes.

"Herero women and children in traditional costume; Sehitwa, Ngamiland." (Circa1940)

Many children wear leather aprons when they are not in school. Men wear mostly store bought clothes but when they participate in the annual days of Herero cultural celebration they wear military type uniforms and bits of animal fur.

Religion: The Herero believe in a Supreme Being, called Omukuru, the Great One, or Njambi Karunga. Like the Himba they also have a holy, ritual fire which symbolizes life, prosperity and fertility to them. However, the majority have been converted to Christianity, although the Herero church, the Oruuano, combines Christian dogma with ancestor worship and magical practices

Herero woman cooking

Before the Genocide Was Committed on Hereros

Africa is almost certainly the birthplace of the human species. From it the earliest people ventured into Asia and then across the long-vanished land bridge to the Americas, or across the Pacific island chains to Australasia. They also spread to the lands north of the Mediterranean Sea.

Many thousands of years later their European descendants gained glory and wealth by rediscovering the southern hemisphere, and plundering it. They – we – have often treated it, and its inhabitants, with brutality, indifference and contempt. White Europeans forced black Africans to become slaves. White Europeans deprived black people of their homes and communities and cultures.

White Europeans sent their missionaries to change black people’s religion to their own. And in the 19th century white Europeans began moving into Africa to occupy the land as well. The land was desirable for itself: it provided new territory, new possessions and new trade, both for individuals and their countries. The land had other values, too: it provided bases for further take-overs and further military threats; and, above all, it contained riches.

Hereros in their hut before the war

Along the coastline of Namibia runs the Namib desert, a 1,200 mile long strip of unwelcoming sand dunes and barren rock. Behind it is the central mountain plateau, and east of that the Kalahari desert. Namibia’s scarcest commodity is water: this is a country of little rainfall, and the rivers don’t always run. But the very sand of the Skeleton Coast is the dust of gemstones; uranium, tin and tungsten can be mined in the central Namib, and copper in the north; and in the south there are diamonds.

Namibia also has gold, silver, lithium, and natural gas. For most of the region’s history, only metal was of interest to the native tribes. These tribes lived and traded together more or less peacefully, each with their own particular way of living, wherever the land was fertile enough. The San were nomads, hunters and gatherers. The Damara hunted and worked copper. The Ovambo grew crops in the north, where there was more rain, but also worked in metal. The Nama and the Herero were livestock farmers, and they were the two main tribes in the 1840s when the Germans (first missionaries, then settlers, then soldiers) began arriving in South West Africa.

Herero - Near old German mission cemetery in Okahandja - Otjozondjupa Region - 1900

Before the Germans, only a few Europeans had visited it: explorers, traders and sailors. They opened up trade outlets for ivory and cattle; they also brought in firearms, with which they traded for Namib treasures. Later, big guns and European military systems were introduced. The tribes now settled their disputes with lethal violence: corruption of a peaceful culture was under way.

Hendrik Witbooi (sitting on the chair) with fighters of the Nama tribe, ca 1904-1905

During The Berlin Conference of 1888 Germany was awarded South West Africa (what is now called Namibia). The Germans made South West Africa their own colony, and settlers moved in, followed by a military governor who knew little about running a colony and nothing at all about Africa. Major Theodor Leutwein began by playing off the Nama and Herero tribes against each other. More and more white settlers arrived, pushing tribesmen off their cattle-grazing lands with bribes and unreliable deals. The Namib’s diamonds were discovered, attracting yet more incomers with a lust for wealth.

German colonial administrator Theodor Gotthilf Leutwein (seated left) and Herero Supreme Chief Maharero - 1895

Tribal cattle-farmers had other problems, too: a cattle-virus (rinderpest) epidemic in the late 1890s killed much of their livestock. The colonists offered the Herero aid on credit. As a result the farmers amassed large debts, and when they couldn’t pay them off the colonists simply seized what cattle were left. In January 1904, the Herero, desperate to regain their livelihoods, rebelled. Under their leader Samuel Maherero they began to attack the numerous German outposts. Chief Maharero gave very specific instructions that only farmers, traders and soldiers would be attacked. He explicitly stated that missionaries, Britons and Boers were not to be harmed. In most cases, the Herero warriors followed Maharero's instructions to the letter - sparing women, children, missionaries and non-Germans. The Herero cut telegraph wires, destroyed railway lines, stole cattle and overran smaller military stations. Initially about 150 Germans were killed, which provoked colonial outrage. The mere fact the 'savages' had the audacity to challenge white claims of superiority and lands in 'their colony', enhanced racist attitudes which had always been rife amongst the settler population.

Chief Samuel Maherero, the leader of Herero tribe

At the same time, the Nama chief, Hendrik Witbooi, wrote a letter to Theodor Leutwein, telling him what the native Africans thought of their invaders, who had taken their land, deprived them of their rights to pasture their animals on it, used up the scanty water supplies, and imposed alien laws and taxes. His hope was that Leutwein would recognise the injustice and do something about it.

Chief Witbooi of the Namaq Tribe

THE GERMAN COLONIAL WAR OF ANNIHILATION AGAINST THE HERERO NATION

“I, the great general of the German soldiers, send this letter to the Herero people. The Hereros are no longer German subjects. They have murdered and robbed, they have cut off the ears and noses and privy parts of wounded soldiers, and they are now too cowardly to fight. I say to the nation: Any person who delivers one of the Herero captains as a captive to a military post will receive 1,000 Marks. The one who hands over Samuel will receive 5,000 Marks. All Herero must leave the country. If they do not, I will force them with cannons to do so. Within the German frontier every Herero, with or without a gun, with or without cattle, will be shot. I will not take over any more women and children, but I will either drive them back to your people or have them fired on. These are my words to the Herero people. The great General of the Mighty Kaiser, von Trotha.”

On 9 September 2001, the Herero People's Reparations Corporation lodged a claim in a civil court in the US District of Columbia. The claim was directed against the Federal Republic of Germany, in the person of

the German foreign minister, Joschka Fischer, for crimes against humanity, slavery, forced labor, violations of international law, and genocide.

909.

Ninety-seven years earlier, on n January 1904, in a small and dusty town in central Namibia, the first genocide of the twentieth Century began with the eruption of the Herero—German war.' By the time

hostilities ended, the majority of the Herero had been killed, driven off their land, robbed of their cattle, and banished to near-certain death in the sandy wastes of the Omaheke desert.

The survivors, mostly women and children, were incarcerated in concentration camps and put to work as forced laborers (Gewald, 1995; 1999: 141—91). Throughout the twentieth Century, Herero survivors and their descendants have struggled to gain recognition and compensation for the crime committed against them.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, the Hereros numbered approximately 80,00020 in Hereroland (also known as South West Africa, today Namibia), where the German colonial enterprise lasted from 1884 to 1919. The German merchant Adolf Lideritz purchased the harbor of

Angra Pequena and its surrounding lands, located on the southern coast of present-day Namibia, in 1883 and began calling for German protection. The following year, Germany declared Lideritz's land a protectorate. The Herero Nation, seeking military support in conflicts with the Nama, another indigenous nation in the region, entered into a treaty of friendship and protection with the German government in 1885. The German colonial policy of divide and rule saw governor Theodore Leutwein in 1894 recognise Samuel Maherero, a faction to the vacant Herero throne and a preferred educated businessman who sold lands to Germans, rather than the more traditional Asas Rirua, as successor to Chief Tjamuaha of the Hereros. The Herero Nation withdrew from the treaty when the Germans were unable to provide the expected military assistance." The treaty was later revived and a further peace agreement was concluded in 1894, but the German colonial administration did not "exercise sovereignty over the territory as it was internationally demarcated" until 1907. The first Herero uprising on March 14 1897 failed, but seven years later, Samuel Maherero, sobered by the land-grabbing of the Germans, rose with his people at Okahandja in May 1904, killing every German farmer and trader they could and seizing 25 000 head of cattle. .Nonetheless, Germany retained power in South West Africa until 1919, when it lost its colonies as a result of World War I. This Part details the German colonial administration's war of annihilation against the Hereros at the beginning of the twentieth century and establishes that this conduct constituted a form of genocide.

Herero familyBeginning of the German-Herero War

In 1904 Germany began a war of annihilation against the Hereros in retaliation for the Hereros' resistance against the German colonial administration's oppressive treatment. The German-Herero War was one of the world's bloodiest conflicts occurring between 1815 and 1914. From the beginning of the war, many Germans supported the total annihilation of the Hereros.

Two days after the Hereros began resisting the colonial administration, the German Colonial League's Executive Committee released apamphlet calling for a swift and harsh response. A letter written by a German missionary to his colleagues captures the violent sentiment among Germans in Hereroland supporting the annihilation of the Hereros:

"The Germans are consumed with inexpiable hatred and a terrible

thirst for revenge, one might even say they are thirsting for the

blood of the Herero[s]. All you hear these days is "make a clean

sweep, hang them, shoot them to the last man, give no quarter." I

shudder to think what may happen in the months ahead. The

Germans will doubtless exact a grim vengeance."

The diaries, letters, and photographs of contemporaries graphically portray the indiscriminate shootings, hangings, and beatings which were the order of the day. Missionary Elger, stationed in the settlement of

Karibib, described the manner in which Herero prisoners were treated:

Things proceeded in a particularly brutal manner. Herero prisoners were terribly

maltreated, whether they were guüty or not guilty. About 4 Herero were

taken prisoner, because they were supposed to have killed a railway worker

(Lehmann, Habis). The court martial ordered them to be freed and declared

them to be not guilty. However one could not release them as they bore too

many marks of shameful abuse [Schandlicher Misshandlung] on their bodies. For

example, people had beaten an eye out of one. After the court martial had

declared them to be innocent, some of the Germans outside immediately resumed

the abuse with the words, 'the court has declared you to be innocent,

we however want to string you up."

Battle of okahandja on Hereros

Some German politicians did oppose the policy of annihilation. In March 1904 August Bebel, the leader of the Social Democratic Party, objected in the German parliament to German troops' barbarous treatment of

the Hereros. Likewise, Theodor Leutwein, the German governor of South West Africa, criticized the annihilation on economic grounds, arguing that Herero laborers were necessary for the success of the colonial enterprise.

Herero fighters with their weapons

In April 1904, three months after the war began, the German Emperor Wilhelm II appointed Lieutenant-General Lothar von Trotha as commander-in-chief of the German forces in South West Africa. Von Trotha had already become well known for his brutal suppression of indigenous

resistance efforts in the 1896 East African Wahehe Rebellion and the 1900-1901 Boxer Rebellion in China. By November 1904 von Trotha had informed Governor Leutwein that "[h]is Majesty the Emperor only said that he expected me to crush the rebellion by fair means or foul," and that "[i]t was and remains my policy to apply this force by unmitigated terrorism and even cruelty. I shall destroy the rebellious tribes by shedding rivers of blood and money.

Governor Theodore Leutwein with the captain of the namaque (Orlam) Hendrik Witbooi (left) and the leader of the Herero Mahahero Samuel (right)

The Extermination Order

Under the command of von Trotha, the German army sought to engineer a crushing defeat of the Herero in the vicinity of the Waterberg (Pool, 1979: 210—11). In keeping with von Moltke's principles of separate deployment and encirclement, von Trotha sent his armies to annihilate the Herero at the Waterberg. Or, as he put it in his own words:

My initial plan for the Operation, which I always adhered to, was to encircle the

masses of Hereros at Waterberg, and to annihilate these masses with a simultaneous

blow, then to establish various stations to hunt down and disarm the

splinter groups who escaped, later to lay hands on the captains by putting prize

money on their heads and formally to sentence them to death. (von Trotha's

diaries cited in Pool, 1991: 251).

On 11 August, the battle of Hamakari at the Waterberg took place. The Herero were defeated and fled in a southeasterly direction into the dry desert sands of the Kalahari, known to the Herero as the Omaheke. It is estimated that up to 2000 pastoralist Herero escaped eastward in small numbers into the Kalahari desert, into what was then the British protectorate of Bechuanaland (Botswana). Included was Samuel Maharero, the Herero leader. His people arrived with little or no cattle and became subservient to the Tswana - Bechwana chieftain of Sekgathôlê a Letsholathêbê. Von Trotha promptly translated his intention to destroy the Hereros into official policy. On October 2, 1904, von Trotha issued an annihilation order stipulating:

The Herero people must ... leave the land. If the populace does not do this I

will force them with the Groot Rohr [cannon]. Within the German borders

every Herero, with or without a gun, with or without cattle, will be shot. I will

no longer accept women and children, I will drive them back to their people

or I will let them be shot at.

These are my words to the Herero people.

[Signed] The great General of the mighty German Kaiser."

Captured and photographed Herero

A number of authors have sought to deny or at least downplay the existence and implications of Trotha's proclamation, which has become known as the extermination order (Vernkhtungsbefehl) . However, Trotha's

own words, in his diary and elsewhere, indicate that hè understood the implications of his proclamation füll well. On the day the proclamation was issued, Trotha wrote in a letter:

I believe that the nation as such should be annihilated, or, if this was not

possible by tactical measures, have to be expelled from the country by operative

means and further detailed treatment. This will be possible if the water-holes

from Grootfontein to Gobabis are occupied. The constant movement of our

troops will enable us to find the small groups of the nation who have moved

back westwards and destroy them gradually....

My intimate knowledge of many central African tribes (Bantu and others)

has everywhere convinced me of the necessity that the Negro does not respect

treaties but only brute force. (Pool, 1991: 272-4)"

Chained hereros

An official report sent two days later by von Trotha to the chief of the army general staff underlined the intent of the extermination order:

'The crucial question for me was how to bring the war against the