ANDAMANESE TRIBE: ONE OF THE EARLIEST AFRICAN NATIVES OF ASIA AND THE ORIGINAL INHABITANTS OF INDIA

The Andamanese tribe may today be seen as facing extinction and still consigned to the hinterlands of India where they suffer massive humiliation as a group of black Africans, but they are one of the original Africans (blacks) who inhabited Asia and the country India before the arrival of the Mangolians or so-called Asians. Out of India`s over 1 billion population, Andamanese population is now below 350. This special group of ancient African Indians and bona fide owners of India as a country will gradually fade out of the world if proper international humanitarian attention is not given to them.

Tourists Treating Indigenous Andaman Islands Jarawa Tribe Like ‘Human Zoo’

Recently the Indian government was using them as "human zoo" to attract tourism to India. Now tourism companies are operating daily “safaris” through natives’ jungle and wealthy tourists are allegedly paying police to make the women — typically naked — dance for their amusement. “It’s deplorable. You cannot treat human beings like beasts for the sake of money.” That is the statement made by India’s Tribal Affairs Minister V. Kishore Chandra Deo on Wednesday after an investigation was launched into a depraved tourist-attraction promoting “human zoos.”

A group of northern Andamanese using their bows for fishing (photograph from Radcliffe-Broewn, ca. 1906)

A group of northern Andamanese using their bows for fishing (photograph from Radcliffe-Broewn, ca. 1906)

The Andamanese people are the various aboriginal inhabitants of the Andaman Islands, a district of India, located in the southeastern part of the Bay of Bengal.

The Andamanese are anthropologically classified as Negritos (sometimes also called Proto-Australoids), together with a few other isolated groups Semang of Malaysia and the Aeta of the Philippines in Asia. They have a hunter-gatherer style of living and appear to have lived in substantial isolation for thousands of years. This degree of isolation is unequaled, except perhaps by the aboriginal inhabitants of Tasmania. The Andamanese are believed to be descended from the migrations which, about 60,000 years ago, brought modern humans out of Africa to India and Southeast Asia. Some anthropologists postulate that Southern India and Southeast Asia was once populated largely by Negritos similar to those of the Andamans and that some tribal populations in the south of India, such as the Irulas are remnants of that period.

A display of southern Great Andamanese weaponry.

By the end of the 18th century, when they first came into sustained contact with outsiders, there were estimated 7,000 Adamanese, divided into five major groups, with distinct cultures, separate domains and mutually unintelligible languages. In the next century they were decimated by diseases, colonial troops, and loss of territory. Today there remain only approximately 400–450 of them; one group has long been extinct, and only two of the remaining groups still maintain a steadfast independence, refusing most attempts at contact.

Andanamese

Andamanese Tribes

It is conventional practice to classify the Great Andamanese into two or three groups: the northern and the southern groups with sometimes a middle group added. This classification is convenient but is based on geography rather than linguistic or cultural criteria. The ten tribes of this group clearly and obviously form one related group.

The differences between the Great Andamanese languages involved mostly the vocabulary and pronunciation rather than grammar and syntax. The myths and legends of all the Great Andaman tribes also give the same picture: they differed in many details but were recognizably from the same stock. The so-called Wot-a-emi legend is particularly interesting. The legend related the belief (common to the tribes living around the A-Pucikwar: the Aka-Bea, Akar-Bale, Aka-Kol and Aka-Kede) that the fire was acquired from the mythical being Biliku at Wot-a-emi on Baratang Island in A-Pucikwar territory. The A-Pucikwar were regarded as the original tribe and they were called "the people who speak Andamanese." Our sources do not name the tribes that did not know of this legend - it could hardly have been current among those who were not aware of the A-Pucikwar's existence.

Names some Great Andamanese tribes had for each other

The most currently recognized group of Andaneme tribe are:

1. ONGE ; These tribe`s population is now less than 100. The Onge are the only easily accessible tribe of the Onge-Jarawa group today. Because of their friendliness and relative accessibility for the past 100 years, more is known about the Onge than about any other living Andamanese group. Almost all of the research on them was done and published after 1950 by scientists working for the Indian Anthropological Survey.

The Onge are now settled in a reservation while the rest of the island is populated by Indian and Nicobarese farmers. Although the administration has corrected many of the early mistakes, it is doubtful whether the Onge can survive as a distinct group. A culture as well-adapted to their environment, as primitive and alien as theirs can only survive in isolation, an isolation that is no longer feasible even if it was seriously attempted.

The tsunami of 24th December 2004 did not affect the Onge much. They knew what to do and suffered no known losses.

Onge family life. Note the traditional attire of the woman on the right and the Indian-style dress of that on the left. Anonymous photographer, 1980s

The Onge, alone among all Andamanese groups, also had acquired (or perhaps retained from ancient times) some skills of seamanship - and with them the ability to travel some distance across the open sea. Onges fished and hunted regularly on and around the uninhabited islands between Little Andaman and Rutland Island. For a few decades during the late 19th and the early 20th centuries they even had a sort of outlying colony on Rutland Island. That similar migrations must has taken place in ancient times and long before the 19th century is indicated by the presence on Great Andaman, North Sentinel island and Rutland island of people related to the Onge: the Jarawa, the Sentineli and the Jangil. The Onge "colonists" of the late 19th century certainly were replacing the fading Great Andamanese of the Aka-Bea tribe when the British first became aware of the situation in the 1890s.

It is likely that the drive of the Onge towards northern hunting grounds after 1890 was caused by the presence of the British and their Indian prisoners in southern Great Andaman. The local tribes there had been weakened by more than 30 years of contact with outsiders and their alien diseases. That the Onge drive towards the north also faded away after some decades could have been for the very same reason.

The Onge have always been less inward-looking and more enterprising than the other Andamanese groups. Their flexibility may have had something to do with their long-term contacts with the outside world.

An Onge hunter saying farewell to his family before setting out.Anonymous photographer, 1980s.

2. THE JARAWA: The Jarawas are said to be the darkest people (sociologically and scientifically speaking and not from a derogatory point of view) in the world.Their population size is now estimated 250 to 400.Jarawa (also sometimes spelt Jarwa, which is closer to the original pronunciation) means "stranger" in the language of the Great Andamanese Aka-Bea . The Jarawa call themselves Ya-eng-nga (which, invevitably, means "human being". Without the characteristic Jarawa prefix ya- this is very close to what the Onge call themselves: en-nge, and which in Onge also has the same meaning as in Jarawa, a major piece of evidence for the long-suspected relationship between the two groups.

The Jarawa are the quintessentially "hostile Andamanese". They seem to have been at war with the Great Andamanese in general and with their main enemy, the Great Andamanese Aka-Bea tribes, for a very long time.

When the British landing party established itself at Port Blair in order to set up a penal colony in 1858 it knew nothing of the Jarawa. They soon heard about them, from their their new Great Andamanese Aka-Bea allies that there was a ferocious tribe hiding in the interior of South Great Andaman. The British paid little attention, being wholly preoccupied with the difficult task of establishing their new penal colony in a climate that seemed to them more hostile than any new tribe could be.

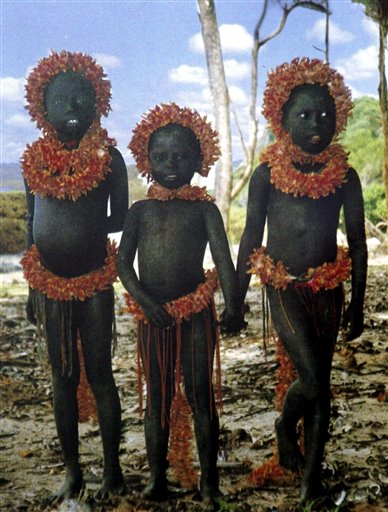

Jarawa people, Andaman Islands, India.

After things had settled down at the new headquarters in Port Blair, time and energy became available for exploratory expeditions into the territory of the mythical Jarawa. While one Great Andamanese tribe after the other was contacted, their lands explored and friendly relations established and new diseases spread to all and sundry, the Jarawa remained stubbornly hostile and resistant to all attempts at establishing contact.

With hindsight, we can now see that a major reason for the relentless hostility was the use of Aka-Bea trackers by the British. These were paid with food, tobacco and alcohol and even issued with arms and ammunition. The British never seem to have questioned the practice on the principle that Andamanese = Andamanese. It took a long time before the British realized (and the realisation never had practical consequences) that Jarawa and the Great Andamanese were hereditary enemies.

A Jarawa man on the Andaman Trunk Road Photo: SURVIVAL INTERNATIONAL

The British were perpetually disappointed when their Aka-Bea allies found nothing but deserted Jarawa villages. They also soon discovered that a Jarawa village, once it had been entered by outsiders, was abandoned by its owners. It was merely chance when, occasionally, elderly men, or women with children were surprised and captured. Such captives were then taken to Port Blair to be "questioned" and given food and gifts. Most soon sickened and many died before they could be returned to the place where they had been captured. This practice of casual kidnapping did nothing to endear the British to the Jarawa and the hostilities continued until the last years of the 20th century.

Jarawa girls

In 1858, Aka-Bea and Jarawa were hereditary enemies that had been fighting each other for a long time, probably centuries. It is an odd fact that when the British in 1790 made contact with natives in the region of Port Blair they found one group hostile and another friendly without realizing that they dealt with two entirely different tribes. Lt. Colebrooke even took some friendly natives with him to Calcutta and to the Nicobars. More than a century later M.V. Portman realized that these early "friendlies" had been Jarawa:

A tourist attraction?: Jarawa children on the Andaman Islands/ Photo credit: The Hindu

The disappearance of the Jarawa from the Port Blair region after the 1790s almost certainly is connected with their early contacts to the British. The diseases that a century later would extinguish their hereditary enemies, quite possibly reduced the number of Jarawa and allowed the Aka-Bea to gain the upper hand. As one British administrator wrote:

... how swift the disastrous effects of our relations with the Andamanese have been to them.

Jarawa man using his teeth to peel coconut

Jarawa people

3. JANGIL or RUTLAND JARAWA: This particular Andamanese are extinct. The interior of the large and hilly island of Rutland, lying just off the south coast of Southern Great Andaman, was home to the most obscure of all Andamanese tribes. For reasons that are not entirely clear, Andamanologists do not so much deny this tribe's separate existence as simply ignore it. On the rare occasions when the Rutland-Jarawa or Rutland-Onge are mentioned at all, it is simply assumed that they were ordinary Jarawa resp. Onge. The interchangeability of the terms "Jarawa" and "Onge" during the 19th century and into the 1930s has done nothing to resolve the confusion.

The last time the Jangil tribe of Rutland was officially mentioned was in the Census of India, 1931, where on page 8 it is stated: "In addition there was a fourth clan of Jarawas of which nothing has been seen since 1907."

Andamanese Jarawa women in traditional attire. Anonymous photographer, 1980s

4. SENTINELESE: their population size is now estimated to be 100 to 200. The Sentineli are the quintessential Andamanese: to this day they live their primitive but comfortable and unhurried lives in complete isolation on a small island, they are hostile to all outsiders and they do not wish to change this state of affairs. Violence is the traditional way to ensure the undisturbed enjoyment of their way of life. In the 21st century, they will kill strangers outright and they hide from landing parties that look too strong to fight. If the landing parties offer coconuts and other goods, they will condescend to accept these, but as soon as the feel they have received enough, an obscene gesture makes clear that the outsiders are no longer tolerated and had better leave in a hurry:

Sentinelese relaxing

The effect of the tsunami of December 2004 on North Sentinel island - geographically - was devastating. For maps on how much the little island was geologically affected by the earthquake (see Tsunami Maps - Sentinel island). The coastline of the entire island was change through a massive tectonic uplift! It is a pity that we do not know what the Sentineli themselves make of it all.

Sentinelese youths

As far as can be observed from afar, all this geological uproar did not affect the Sentineli much, nor has it softened their attitude towards meddlesome outsiders. They might have suffered some losses from the tsunami (we do not know) and they might have had food supply and other problems (we do not know either), but they quite obviously adjusted with amazing speed to their re-shaped island and its changed conditions. It is just as well they did since the outside authorities for months after the major event were fully occupied by first getting their act together and then by keeping an Indian population totally unprepared for such a calamity alive and above the water line.The contrast between the "primitive" but adaptable Sentineli and a modern civilization with all its fragile infrastructure was, and still is, astonishing.

5. Great Andamanese - their population is now about 54. The Great Andamanese of all the Andamanese Negrito came first in close contact with the outside world from 1858 when the British set up a penal colony on the islands. The last remnants of what 150 years ago were around 3,500 people split into 10 related tribes living on most of the Great Andaman islands, have today shrunk to a little more than 30 people living in a reservation on tiny Straits island. During the Tsunami of 26 December 2004 the tribe managed to escaper without loss thanks to the courageous and timely action of their chief, Raja Jirake (see below)

Raja Jirake (ca. 1940-2005), chief of the Great Andamanese and his family, shortly before his death on 17 April 2005

(see Obituary)

Jiroki, chief of the 50-strong Great Andamanese tribe who all survived the tsunami. "I am the king. They follow what I say," he said.Photo: AP

The Andamanese Traditional Society

Social life among traditional Andamanese centred on something called, for want of a better word, the local group. This was a village community, albeit a highly nomadic one. It was in their local group that the Andamanese found peace and a secure place in the world, this was where they felt at home. Membership of a tribe had no practical importance; traditional Andamanese had few if any peaceful dealings with people from outside their own immediate neighbourhood. In most cultures, the family fulfils the emotional and physical functions that in Andamanese society were taken up by the local group. Children were readily adopted away from their parents, descent by blood did not interest anyone much and clans were quite unknown. Children were not expected to show more respect to their parents, real or adopted, than they had to show to all older people. It was age that demanded respect above all else.

Andamanese

Andamanese

Local groups were essentially nomadic, Aryoto somewhat more so than Eremtaga. The groups moved from place to place, wherever the most abundant seasonal food supply could be found, spending only the rainy season in the main camps. Rarely staying at one place outside the main camp for longer than a few weeks, each group remained strictly within its own tiny hunting territory. Any trespassing, let alone poaching, on the land of a neighbouring group would have led to immediate and serious problems. Just how ancient the local groups, their regular trails and campsites could be is shown by the kitchen midden that dot the Andamanese countryside. These are heaps of domestic refuse accumulated when a local group occupied the same site for a period of time year after year for countless generations. The midden are our only source of reliable information about the pre-1858 Andamanese and we shall look more closely at their evidence when we deal with the prehistory of the islands.

Midden were not just piles of domestic refuse that became useful platforms on which to build camps when they had reached a certain size. Their size also reflected the hunting and gathering prowess of the owning group and as such were a source of local pride, serving as a unmistakable markers to the surrounding hunting territory. The symbolic value of a large midden was further strengthened by a link to the group's ancestors by the custom, especially among Onge, to bury their dead or some bones from them under their communal huts, i.e. in the midden. Local pride in their kitchen-midden faded among the Great Andamanese after the 1860s and among Onge after the 1920s with the introduction of the dog. Dogs allowed even the most inept hunter to catch more than enough pigs and made the bow and arrow almost redundant. We find here that helping a primitive group become more efficient can destroy pride in its achievements, undermining the self-confidence necessary for long-term survival.

Beautiful Coastline of the Andamanese Island

The size of local groups has been estimated at between 30 and 50 men, women and children. Each was made up of a few families consisting of father, mother and their unmarried children at the core with unmarried older spinsters and bachelors, widows and widowers and the occasional waif and stray on the fringe. The average group owned a territory of around 40 sq.km (16 sq. miles) while the average tribe consisted of 10 local groups. People were free to leave their own group to take up residence with another and this seems to have been quite a common occurrence. Newly-weds could take up residence wherever they wished: at the local group of the bride or the bridegroom or with any other local group that would accept them. Such movement between friendly local groups was easy but it was normally limited to neighbouring groups. Emigration outside the neighbourhood may have taken place in the old days but must have been rare. A crossing from Aryoto to Eremtaga or across tribal borders would have been unthinkable.

The traditional Andamanese aborigine had a very limited geographical horizon. Members of one group were unaware of the existence of other groups living as little as 30 km (20 miles) away. The ignorance of the traditional Andamanese (apart from the Onge) of their island geography was profound: they knew and cared only about their own hunting grounds and those of their neighbours. The Andamanese seem to have been quite unconscious of being one people and there was no fellow-feeling towards other Andamanese. Quite the contrary, in fact. If a member of one tribe found himself accidentally adrift in his canoe, fetching up on the beach of another tribe, his goose would as surely be cooked as if he had been a shipwrecked British sailor: he would be killed. A feeling of belonging together would only come to the Andamanese after the outsiders and their diseases had cut the ground from under all of them.

The local groups did not have their own names but instead were known by the area they occupied. This could be a major land feature, a hill, a rock, a creek, an island or the name of the main camp-site. For example, a local group of the Aka-Bale tribe living on the island of Teb-juru was known as the Teb-juru-wa, with -wa meaning "people". The northern equivalent of wa was koloko but the system of naming local groups was the same. A local group of the northern Aka-Bo tribe that lived on a creek (buliu) called Terant was known, with irresistible logic, Terant-buliu-koloko. Of 58 place names that could be translated, 39 referred to trees and plants, 12 to topographic features and 7 to socio-cultural aspects. In the old days, it would have been very rare to come across a person from an unknown local group so that the names of local groups became useful only after 1858 when people started to move around and had to identify themselves to strangers.

Several communities at peace with each other and connected by ties of friendship and matrimony, whose members knew and trusted each other and whose ancestors over many generations had done likewise, formed a higher-level grouping, the sept. Social contacts within a sept were frequent and close. Groups met for feasting, dancing and the exchange of gifts, while children were often adopted out to other local groups within the sept where their biological parents could visit them.

The remarkable ceremonial of greeting and the copious tears shed has attracted attention and comment from many observers. The Andamanese did not and still do not lightly show their social emotions. There were no special words for ordinary greetings like the English "hello" or "how-do-you-do." When two Andamanese met who had not seen each other for a while, they first stared wordlessly at each other for minutes. So long could this initial silent staring last that some outside observers who saw the beginning of the ceremony but not its continuation came away with the impression that the Andamanese had no speech. The deadlock was broken when the younger of the two made a casual remark. This opened the doors to an excited exchange of news and gossip. If the two were related, the older would sit down and the younger sit on his lap, then the two would cuddle and huddle while weeping profusely. If they had not seen each other for a long time, the weeping could go on for hours. In the eyes of outside observers, the embracing and caressing could seem amorous but in fact the ceremony had no erotic significance whatsoever. Kisses were not part of the repertoire of caresses; only children received kisses as a sign of affection. Greater Andamanese greeting ceremonies were loudly demonstrative, their weeping often turning into howls that could be heard, as was intended, far and wide. The Onge were less exuberant and were satisfied with the of a few quiet tears and with caressing each other. If there were many people, greeting returning hunters that had been absent longer than expected or meeting unusual visitors, etiquette required that the large mass of people should not cry until several hours after the arrival. When the howling started, it could go on all night. When more than a few people met, the initial staring was dispensed with. The following description of a larger ceremony dates to 1870:

The hunting ground (which among Aryoto groups also included fishing grounds) was the local group's most valuable, indeed its only, possession. It was held in common. The territory provided its members with all the essentials of life. Not surprisingly since the group's survival depended on it, the rights to the land were fiercely defended. So strong was the claim to the ancestral hunting grounds that as late as the early 20th century permission to hunt had to be sought from the owning group even if one frail old survivor was all that was left of it. In happier days, each member of the local group had the right to hunt and gather on the land held by his or her local group. Most borders between territories had been fixed from time immemorial; they were immutable and known to all. Trespassing and poaching could lead to bloody and sometimes long-lasting feuds between neighbours. As we have seen, the relationship between the richer Aryoto and the poorer Eremtaga was at best an uneasy one because the latter could not always resist the temptation the formers' richer territories presented. Generally speaking, borders separating Aryoto and Eremtaga groups were less well-defined than others and seem to have still been in the long drawn-out process of being sorted out through feuds and agreements - until 1858 made it all irrelevant. Local groups had carved up practically all the territory of the Andaman archipelago among themselves, only a few areas like Saddle Peak were avoided by all. In some places long-forgotten border disputes left traces of what must have been negotiated peace accords: there were areas over which two groups could hunt, others where one group had the hunting and another the gathering rights while at still other places two groups could hunt and gather at different times of the year.

The Jarawa tribe of South Andaman Island face increasing intrusion from tourists. Photograph: Gethin Chamberlain/Courtesy of the Andaman Anthropological Museum

The economic life of the traditional local group has been called a sort of communism and yet it was based on the notion of private property. With so few possessions to go round, the concept of private property did not acquire the overwhelming importance that it has in wealthier societies. There was no accumulation of property and practically no difference in wealth between individuals. In such circumstances theft was naturally rare but when one had been committed, it was a serious matter. Private property in traditional Andamanese society was limited to the portable items that each person had made for himself or herself, i.e. bow and arrows, harpoons, pots, nets, ropes and the like. A canoe was made in cooperation by several men under the direction of the owner who would later be obliged in return to help his helpers make their own canoes. In a village, each family erected and kept in repair their own hut. Communal huts were built in cooperation by several families while each family would then live in and be responsible for the upkeep of its own section.

During a successful hunt, the man whose arrow or harpoon had struck the quarry first was its owner. The person who found a beehive only became the owner if he or she climbed up the tree and brought the honeycombs down. The same principle applied to whatever a person could kill, catch, dig up or gather within the tribe's hunting grounds. The lucky owner of any foodstuff was expected to share with those who had little or nothing. While a married man could keep the best parts of his catch for himself and his family, bachelors were expected to distribute most of theirs to the older people. The result was a relatively even spread of the available food through the local group. Generosity towards the members of one's own local group and to friends outside was highly valued. Private property was also respected within the family, neither husband nor wife being free to dispose of the partner's private property.

The Jarawa tribe of South Andaman Island face increasing intrusion from tourists. Photograph: Gethin Chamberlain/Courtesy of the Andaman Anthropological Museum

A more abstract ownership and even something like copyright was also known. Any member of the local group could notify the others that a tree within the group's territory was to be reserved for him because he wished to make a canoe out of its trunk; such claims were respected by the others for years if the owner did not get round to his project immediately. Some men were also reported to have possession of certain fruit trees from which nobody could take fruit without permission and from which the owner expected his share of the picking. Such rights seem somehow alien in the context of traditional Andamanese culture. We do not know whether women could own trees nor do we know how and when the men's rights originated.

The Andamanese copyright was remarkable: songs were specially composed for large gatherings and those that had been successful with the fickle public would on request be repeated at later gatherings. All rights to such stone-age hit songs were reserved by the composer and no one except him (rarely her) was allowed to sing it. If anyone else tried without permission, it would have been regarded as theft. Andamanese songs were highly monotonous and very similar to each other musically. The creative work was in the words.

There was no concept of trade in our sense. In everyday life, a system of gift giving took the place of trade, leading to the mutual obligations that were a mainstay of traditional Andamanese society. Not only on special occasions but even during the daily life of a local group, presents were constantly exchanged. All moveable goods, including canoes and even the skulls of ancestors, could be given away. No one was free to refuse a gift offered. It would also have been the height of bad manners to have refused someone an article that had been requested. However, for every gift received something of roughly equal usefulness or value had to be given in return. Items could pass quite rapidly from person to person and, at least after 1858, could cross tribal borders. A person carrying an ancestral skull around the neck need not necessarily have any idea who the original owner of the skull had been or where the object had come from. The Andamanese saw the exchange of gifts as a moral obligation, as a means to spread friendly feelings and to keep friendships and alliances in good working order. That they could also have a practical value was of secondary importance to them. Eremtaga groups without access to the sea could acquire turtle shells or turtle fat while iron looted from shipwrecks was spread far and wide over the archipelago.

Great Andamanese couple 1876

Gift giving was not always a simple matter, however, and since Murphy's law worked in Andamanese as well as in any other human society, things that could go wrong did go wrong. When the return gift did not come up to the sometimes inflated expectations of the original giver, quarrels and feuds could arise.

It was not until the 1880s that the Greater Andamanese had learnt to sell items such as bows and arrows to outsiders in return for money with which they could buy the items they craved but could not make themselves, such as sugar, tobacco or tea. At the same time some also began to perform traditional dances or sold locks of their hair for money. Nevertheless, the Greater Andamanese never really understood the concept of money and trade. All too often their commercial naivety was shamelessly taken advantage of but this did not seem to upset them. In 1867 the authorities tried to stop the exploitation by forbidding trade between outsiders and Andamanese. Prohibition did not work and business was back to normal soon. The Onge of the 1950s were playing the commercial game more astutely: one scientist who was trying to acquire two canoes for museum collections complained bitterly about the ruthless bargaining he was subjected to. There is a strong suspicion that the Onge may have traded, perhaps for centuries, with Chinese and others, diving for valuable sea shells in return for alcohol and opium. The outsiders would have regarded this as payment for the Onge's work while the Onge themselves would have regarded it as an exchange of gifts. Compared to the other Andamanese groups, a long tradition of contact and trade with the outside world would go some way to explain the Onge's adaptability towards British and later Indian outsiders, their greater commercial sense, their consistent peaceful attitude after the initial period of hostility as well as their more adventurous attitude towards the sea.

The possibility that at least some Great Andamanese groups practiced what is known as "silent trade" has been mooted and there is indeed some indirect evidence but no definitive proof. It should be noted that a society of complete hunter-gatherers is largely self-sufficient and is not under any great pressure to trade with the outside world. Traditional Andamanese are known to have been greedy for iron for a long time but their survival did not depend on the metal. If they could not get it, they had alternative traditional technologies to fall back on.

The daily routine in the succession of temporary camps that was traditional Andamanese life was dominated by the women. The men were too often away on hunting trips during the day to play an active part in camp life. The weather had to be inclement indeed to keep them from going out to hunt and in really bad weather not much could be done around the camp anyway. Not to put too fine a point on it, the Andamanese male traditionally shirked work in camp.

Visiting friends in other local groups was a major source of pleasure for traditional Andamanese. Visits by a single person or a whole family could take place at any time of the year but tended to concentrate on the months of the year between December and May when the weather was calm and stable. Married couples naturally wished to visit the local group in which one partner was born but in which they had chosen not to live. Parents of children adopted away also were keen to pay a visit and to see how their children were getting on. Hospitality towards friends was an important duty so that such visitors were sure to receive an enthusiastic welcome and the best food available.

Andamanese are the last archers of Asia

More formal social gatherings, called jeg, were organized by influential individuals who decided on a time and place and who sent out the invitations by messenger. The host group was responsible for housing and feeding the guests. For the first few hours after their arrival, all would feel a little shy and awkward, a feeling not unknown at similar gatherings in more advanced civilizations. Visitors and guests then exchanged gifts such as clay for body painting, bows and arrows, baskets etc. This was a delicate moment when the diplomatic abilities of the presiding chief could be tested to their limits. If a quarrel broke out it would diminish respect for the man in charge if he could not quietly and discreetly defuse the situation. With the highly excitable Andamanese temperament and a tendency to take offence at the slightest provocation, any gathering was potentially explosive. Larger meetings often were called to put the official seal on the reconciliation after an old quarrel had been settled. A chief could gain much additional influence and respect from running a successful meeting but he could also ruin his position if something went seriously wrong. Some meetings of reconciliation ended as the starting point of a new feud.

We have seen that the Andamanese were individualists and not inclined to take orders from a person they did not respect. No one commanded and no one obeyed. It all had to be voluntary or required by tradition, there being nothing like a structure of government. Chiefs existed but had no power to enforce their will on anyone; they were only men of influence. A chief reached his position through strength of character; heredity played no role whatever. A headman had to rely exclusively on respect and reputation to keep his followers in line and loyal. Decisions were taken by all grown-up older men with the older women given a considerable voice as well. Younger people were expected to show respect towards their elders and their opinions counted for less but they were free to voice them and were listened to. The final decision was taken by general consent among the older members of the group. It was the headman alone, however, who directed the movements of hunting parties and who made all decisions that had to be taken quickly on the spot. He was also in charge of the meetings and festivities. Some headmen, again exclusively by strength of character, rose to be heads of a whole sept and even of a group of septs. None could acquire headship over an entire tribe, however, if that tribe was split into Aryoto and Eremtaga sections since none of these groups would accept a headman from the other section. The power a high-level headman could yield was limited by his personality as much as it had been at a lower level. Tradition prevented women from becoming chiefs, however strong their character but the wife of a headman enjoyed the same position relative to the women that her husband had with the men.

The British, military men and colonial administrators to whom a strictly hierarchical regime was second nature, understandably took a dim view of this unfamiliar, formless, almost democratic non-government. After looking in vain for chiefs with the sort of authority a chief was expected to have over his subjects, they solved their administrative problem by creating a system of chieftainships and by appointing intelligent and trustworthy natives to the position of "rajas" as intermediaries between natives and colonial authorities. The Indian title of raja (king) was rather preposterous for such local appointees but it caught on. The Andamanese did not readily accept the authority of the new rajas but followed them of their own free will if they could gain their respect. Most rajas were, in fact and unsurprisingly, the traditional local headmen.

The Andamanese system of social ranking was based very strongly on age. Old people, men and women, had to be shown respect. They received the best pieces of any hunting success of younger men and they made all the important decision affecting the group. It was also they who made and unmade chiefs. Old men took the most beautiful of the younger women as wives as we have already seen - with entirely predictable effects on the birth rate. In many way traditional Andamanese society functioned as a gerontocracy. Considering the relatively heavy burden that the old put on the young, it is surprising how little grumbling there was among the victims of the system even when traditional society was disintegrating in the second half of the 19th century. We know nothing about the thoughts of young people during the old days but we can safely assume that they took it for granted, consoling themselves with the thought that in the fullness of time they would reach the same privileged position. The duty that one person owed another was not so much governed by the degree of relatedness or marriage as by relative age. What duties a child owed to his parents or a man and woman to his or her older siblings differed little from what the same persons owed to any other person of comparable relative age. Relationships between child and parents had, of course, a somewhat different quality from other relationships but the peculiar system of adoptions shows that this difference at least from age six upwards should not be over-estimated. Most societies, primitive or advanced, have high respect for the old but few have carried the principle to such lengths.

While social status was very closely connected with age, there were other ways to gain a better position in society. Hunting prowess was high on the list for men but generosity and kindness towards members of the local group and other friends (but never to outsiders) was also highly esteemed in both sexes. A person with a violent temper, on the other hand, was feared but not respected. A chief bursting out in a fit of bad temper would make everyone run for cover - but he diminished his own authority which he would later find difficult to re-establish.

The grip of tradition was tight in the Andamans but it was their own tradition, they were happy with it. Everybody was left with a considerable margin of individual freedom and the work that had to be done was done communally and was rarely arduous. There was no harsh compulsion, just the gentle if insistent tug of tradition. The hunt was as much pleasure, the gathering as much social event as they were work and necessity. Many well-meaning outside officials working with the Andamanese pitied the "poor creatures" and patronized them in their "wretched and miserable condition." They felt duty-bound to improve them, by force if necessary, thereby involuntarily hastening the extinction of the race. For their own part, the Andamanese tried to avoid being drawn into alien ways of life. All those groups who did not or could not keep their distance are now either extinct or heading that way. The traditional Andamanese, embedded in their largely undisturbed society, did not see their condition as wretched. It is hard to blame the Andamanese when they refused a life, however civilized, of paid drudgery in fields, plantations or factories. Even worse, in many ways, was the option of receiving free government handouts with nothing left to do. The Andamanese were (and the Jarawa and Sentineli certainly still are today even if we cannot ask them) quite satisfied with the lifestyle that had been good enough for their ancestors for untold millennia. It was not paradise but it was home. Only with the onslaught of epidemics and the disintegration of their society did the word "wretched" begin to fit reality.

One sad and revealing Indian photograph dated to around 1980 shows a number of Onge plantation workers sitting on felled logs during a break in their work. No less sad and revealing is a British description of the Andamanese playing the amusing fools at a social event of fashionable colonial society at Port Blair 1885:

Andamanese girl in India

Myths and Legends

As Radcliffe-Brown, to whom we owe this story, remarks, the above is hardly comprehensible without a little explanation. Indeed not. His comments on some key words are listed here as follows:

Legend: Floods and draughts

Human life in the Andamans was not only under threat from the rising sea and of storms. Rainfall can be unpredictable enough to create occasional droughts. It therefore does not come as a surprise that there are legends dealing with droughts. One relates how a woodpecker discovered a honeycomb during the dry period. While eating, the woodpecker noticed a toad wistfully observing him. The woodpecker invited him as his guest and sent a liana down to fetch the toad. Just before his guest had reached the site of the feast, the woodpecker mischievously dropped him to the ground. This so exasperated the toad that he went to all the streams of the land and drank them dry. The failure of the streams led to great distress in the islands. The toad was delighted with his revenge and commenced to dance, whereupon all the water flowed from him and the draught was ended. Unfortunately, unlike the flood stories, there is no archaeological evidence yet for draughts - but on climatological grounds they must have taken place on the islands.

Legend: Pigs

A few minor legends and superstitious practices exist regarding the pig. In view of its importance, its central position in daily life, it is indeed remarkable how rarely the pig appears in Andamanese myths and legends and indeed in religious belief. Yet pig skulls have been collected and kept as hunting trophies by all Andamanese, even by the isolated Sentinelis, to an extent that would almost demand a cult of the pig. Other animals, especially birds and including many other animals that we have not had the space to mention here, pop in and out of the tales with abandon. Not so the pig. Very few legends about the origin of pigs are known. One is from the Aka-Kede:

A human ancestor, the civet cat, invented a new game and made some ancestors run on all fours and grunt. Those who played turned into pigs.' Another story on how the pigs got their senses we have already met earlier. And that is it, more or less.

According to the archaeological evidence, the pig was introduced to the Andamans relatively late from the outside, probably shortly before 2,200 or so years ago and perhaps together with pottery and possibly even by the same mysterious visitors. Is it really only coincidence that pottery, too, is remarkable by its near-absence from legend and myth in the islands? It would be interesting to speculate that if events more than two millennia ago had so little impact on Andamanese legends, the age of the tales told might be immense. Speculating is one thing, proving it something else.

Legend: Discovery of iron

Another interesting legend deals with the discovery of iron. The archipelago does not have any known iron deposits and all iron used by the natives is thought to have come from plundered shipwrecks and lately from raids on outsiders' settlements and trade. The following story indicates that at least a tiny amount of iron may also have come from meteoritic sources:

One day, Tomo (in this story called Duku) went on a fishing expedition and shot an arrow. He missed his object and instead struck a hard substance that proved to be a piece of iron. The legend states that this was the first iron found by the natives. From the new substance, Duku made himself an arrow-head with which he also scarified (tattooed) himself. He then sang a ditty to the effect that now that he was scarified nothing could strike him.

Legend: Large beasts

Throughout the Andamanese tribes there was a belief in huge, mythical land animals that are said to have lived in the jungles of the archipelago during the earliest days of the ancestors. In the northern parts of Greater Andaman they were known as Jirmus while the southern Akar-Bale knew something similar as Kocurag-boa. The Aka-Bea had their Ucu who is said to have eaten so many people that it got stuck in mud and died. When elephants were first introduced into the Andamans in the 19th century, the Aka-Bea immediately called it Uca and the northern tribes Jirmu. Nothing bigger than the Andamanese pig could have roamed the islands for a very long time (unless one includes whales in the story). From the vague descriptions supplied by the legends, the giant beasts sound like a mixture of tiger and elephant, both native to the Asian mainland surrounding the Andaman sea. The legends may well be a last faint echo of the times before 8,000 years ago, when tiger and elephant were cut off in the Andamans (which was not a peninsula, though at the time of the lowest sea level, the straits between the Andamans and mainland Asia in the north was indeed narrow enough for larger animals to swim across). The sea has been rising ever since and the large beasts along with their human Negrito contemporaries were cut off from Asia. Elephant and tiger (if it was them) could well have lost in the competition for shrinking hunting and grazing grounds against the human ancestors of the present Andamanese.

Andamanese girl

For further comprehensive information on Andamanese see:http://www.andaman.org/BOOK/text-group-BodyChapters.htm.

Read more athttp://news.mongabay.com/2010/0204-andaman.html#bV9EhpsJhP6CcGGd.99Boa Sr, the last speaker of ‘Bo’, one of the ten Great Andamanese languages, died last week, according to an indigenous rights group. She was 85.

Her death marks the extinction of the Bo, a group thought to have lived on the Andaman Islands for as much as 65,000 years, "making them the descendants of one of the oldest human cultures on Earth," according to Survival International.

The tribe was decimated when the British colonized the Andaman Islands in 1858. The Bo died at the hands of British soldiers and of introduced disease.

Boa Sr, the last member of the Bo tribe. © Alok Das

Boa Sr was the oldest of the Great Andamanese, a group of ten tribes. There are now only 52 living Great Andamanese, most of whom are destitute, according to Survival International's director Stephen Corry.

."The Great Andamanese were first massacred, then all but wiped out by paternalistic policies which left them ravaged by epidemics of disease, and robbed of their land and independence," he said in a statement.

"With the death of Boa Sr and the extinction of the Bo language, a unique part of human society is now just a memory. Boa’s loss is a bleak reminder that we must not allow this to happen to the other tribes of the Andaman Islands."

The late Boa Sr and her family

Survival International is working to help the Jarawa, an Andaman tribe that resisted contact with outsiders until 1998. The group has since been decimated by measles.

PHOTOS OF ANDAMANESES

Jarawa group ca. 200 Photo courtesy Wilhelm Klein

Jarawa girl

Jarawa girl with her baby

Jarawa people bathing at the beach

Jarawa girl carrying Banana

Andamanese swimming

An elated Andamanese girl

Andamanese girls

Jarawa woman with her unique tribal baby sling

Mion(L), a member of near extinct Great Andamanese aboriginal tribe, sits with his sister Ichika

© AFP/File Pratap Chakravarty

Recently the Indian government was using them as "human zoo" to attract tourism to India. Now tourism companies are operating daily “safaris” through natives’ jungle and wealthy tourists are allegedly paying police to make the women — typically naked — dance for their amusement. “It’s deplorable. You cannot treat human beings like beasts for the sake of money.” That is the statement made by India’s Tribal Affairs Minister V. Kishore Chandra Deo on Wednesday after an investigation was launched into a depraved tourist-attraction promoting “human zoos.”

“Whatever kind of tourism is that, I totally disapprove of that and it is being banned also,” the minister added.

A group of northern Andamanese using their bows for fishing (photograph from Radcliffe-Broewn, ca. 1906)

A group of northern Andamanese using their bows for fishing (photograph from Radcliffe-Broewn, ca. 1906)The Andamanese people are the various aboriginal inhabitants of the Andaman Islands, a district of India, located in the southeastern part of the Bay of Bengal.

The Andamanese are anthropologically classified as Negritos (sometimes also called Proto-Australoids), together with a few other isolated groups Semang of Malaysia and the Aeta of the Philippines in Asia. They have a hunter-gatherer style of living and appear to have lived in substantial isolation for thousands of years. This degree of isolation is unequaled, except perhaps by the aboriginal inhabitants of Tasmania. The Andamanese are believed to be descended from the migrations which, about 60,000 years ago, brought modern humans out of Africa to India and Southeast Asia. Some anthropologists postulate that Southern India and Southeast Asia was once populated largely by Negritos similar to those of the Andamans and that some tribal populations in the south of India, such as the Irulas are remnants of that period.

A display of southern Great Andamanese weaponry.

By the end of the 18th century, when they first came into sustained contact with outsiders, there were estimated 7,000 Adamanese, divided into five major groups, with distinct cultures, separate domains and mutually unintelligible languages. In the next century they were decimated by diseases, colonial troops, and loss of territory. Today there remain only approximately 400–450 of them; one group has long been extinct, and only two of the remaining groups still maintain a steadfast independence, refusing most attempts at contact.

Andanamese

Andamanese Tribes

It is conventional practice to classify the Great Andamanese into two or three groups: the northern and the southern groups with sometimes a middle group added. This classification is convenient but is based on geography rather than linguistic or cultural criteria. The ten tribes of this group clearly and obviously form one related group.

The differences between the Great Andamanese languages involved mostly the vocabulary and pronunciation rather than grammar and syntax. The myths and legends of all the Great Andaman tribes also give the same picture: they differed in many details but were recognizably from the same stock. The so-called Wot-a-emi legend is particularly interesting. The legend related the belief (common to the tribes living around the A-Pucikwar: the Aka-Bea, Akar-Bale, Aka-Kol and Aka-Kede) that the fire was acquired from the mythical being Biliku at Wot-a-emi on Baratang Island in A-Pucikwar territory. The A-Pucikwar were regarded as the original tribe and they were called "the people who speak Andamanese." Our sources do not name the tribes that did not know of this legend - it could hardly have been current among those who were not aware of the A-Pucikwar's existence.

| Name with translation | Aka-Bea | Akar-Bale | A-Pucikwar | Oko-Juwoi | Aka-Kol |

| Aka-Bea fresh water | Aka-Bea-da | Akat-Bea | O-Bea-da | Aukau-Beye-lekile | O-Bea-che |

| Akar-Bale on the opposite side of the sea | Aka-Balawa | Akar-Bale | O -Pole-da | Aukau-Pole-lekile | O-Pole-che |

| A-Pucikwar they speak Andamanese | Aka-Bojigyab-da | Akat-Bojig-yuab-nga | O-Pucikwar-da | Aukau-Pucik-yar-lekile | O-Pucikwar-che |

| Oko-Juwoi they cut pattern in their bows | Aka-Juwai-da | Akat-Juwai | O-Juwai-da | Aukau-Juwoi-lekile | O-Juwai-che |

| Aka-Kol bitter or salty taste | Aka-Kol-da | Akat-Kol | O-Kol-da | Aukau-Kol-lekile | O-Kol-che |

The most currently recognized group of Andaneme tribe are:

1. ONGE ; These tribe`s population is now less than 100. The Onge are the only easily accessible tribe of the Onge-Jarawa group today. Because of their friendliness and relative accessibility for the past 100 years, more is known about the Onge than about any other living Andamanese group. Almost all of the research on them was done and published after 1950 by scientists working for the Indian Anthropological Survey.

Sadly, the Onge like other Andamanese groups, also seem to be on their way to extinction. Friendliness in the Andaman islands has not historically been a helpful trait in the struggle for survival.

Until the late 1940s, the Onge were the sole permanent occupants of Little Andaman. Before that time, they led a largely traditional way of life despite indications of some traditional trading activity with outsiders (probably Malay and/or Burmese).

Onge woman and child

Onge woman and child

The British controlled the island after the late 1890s. M.V. Portman enforced a degree of British authority over the Onge and establish direct contact with a tribe that until his arrival had been hostile. From the early 1900s onwards, the Onge had only intermittent contact with their nominal British overlords and continued their traditional life undisturbed. On their part, the British were only concerned to keep the island peaceful and out of the hands of other powers, only interfering if they felt their own position threatened or when shipwrecked sailors were molested by Onge goups. During the Japanese occupation of the islands (1942-1945) the short-lived new masters took the same attitude, stationing only a few soldiers on the island to observe shipping movements. They largely ignored the Onge.

The tsunami of 24th December 2004 did not affect the Onge much. They knew what to do and suffered no known losses.

Onge family life. Note the traditional attire of the woman on the right and the Indian-style dress of that on the left. Anonymous photographer, 1980s

The Onge, alone among all Andamanese groups, also had acquired (or perhaps retained from ancient times) some skills of seamanship - and with them the ability to travel some distance across the open sea. Onges fished and hunted regularly on and around the uninhabited islands between Little Andaman and Rutland Island. For a few decades during the late 19th and the early 20th centuries they even had a sort of outlying colony on Rutland Island. That similar migrations must has taken place in ancient times and long before the 19th century is indicated by the presence on Great Andaman, North Sentinel island and Rutland island of people related to the Onge: the Jarawa, the Sentineli and the Jangil. The Onge "colonists" of the late 19th century certainly were replacing the fading Great Andamanese of the Aka-Bea tribe when the British first became aware of the situation in the 1890s.

It is likely that the drive of the Onge towards northern hunting grounds after 1890 was caused by the presence of the British and their Indian prisoners in southern Great Andaman. The local tribes there had been weakened by more than 30 years of contact with outsiders and their alien diseases. That the Onge drive towards the north also faded away after some decades could have been for the very same reason.

The Onge have always been less inward-looking and more enterprising than the other Andamanese groups. Their flexibility may have had something to do with their long-term contacts with the outside world.

An Onge hunter saying farewell to his family before setting out.Anonymous photographer, 1980s.

2. THE JARAWA: The Jarawas are said to be the darkest people (sociologically and scientifically speaking and not from a derogatory point of view) in the world.Their population size is now estimated 250 to 400.Jarawa (also sometimes spelt Jarwa, which is closer to the original pronunciation) means "stranger" in the language of the Great Andamanese Aka-Bea . The Jarawa call themselves Ya-eng-nga (which, invevitably, means "human being". Without the characteristic Jarawa prefix ya- this is very close to what the Onge call themselves: en-nge, and which in Onge also has the same meaning as in Jarawa, a major piece of evidence for the long-suspected relationship between the two groups.

The Jarawa are the quintessentially "hostile Andamanese". They seem to have been at war with the Great Andamanese in general and with their main enemy, the Great Andamanese Aka-Bea tribes, for a very long time.

When the British landing party established itself at Port Blair in order to set up a penal colony in 1858 it knew nothing of the Jarawa. They soon heard about them, from their their new Great Andamanese Aka-Bea allies that there was a ferocious tribe hiding in the interior of South Great Andaman. The British paid little attention, being wholly preoccupied with the difficult task of establishing their new penal colony in a climate that seemed to them more hostile than any new tribe could be.

Jarawa people, Andaman Islands, India.

After things had settled down at the new headquarters in Port Blair, time and energy became available for exploratory expeditions into the territory of the mythical Jarawa. While one Great Andamanese tribe after the other was contacted, their lands explored and friendly relations established and new diseases spread to all and sundry, the Jarawa remained stubbornly hostile and resistant to all attempts at establishing contact.

With hindsight, we can now see that a major reason for the relentless hostility was the use of Aka-Bea trackers by the British. These were paid with food, tobacco and alcohol and even issued with arms and ammunition. The British never seem to have questioned the practice on the principle that Andamanese = Andamanese. It took a long time before the British realized (and the realisation never had practical consequences) that Jarawa and the Great Andamanese were hereditary enemies.

A Jarawa man on the Andaman Trunk Road Photo: SURVIVAL INTERNATIONAL

The British were perpetually disappointed when their Aka-Bea allies found nothing but deserted Jarawa villages. They also soon discovered that a Jarawa village, once it had been entered by outsiders, was abandoned by its owners. It was merely chance when, occasionally, elderly men, or women with children were surprised and captured. Such captives were then taken to Port Blair to be "questioned" and given food and gifts. Most soon sickened and many died before they could be returned to the place where they had been captured. This practice of casual kidnapping did nothing to endear the British to the Jarawa and the hostilities continued until the last years of the 20th century.

Jarawa girls

In 1858, Aka-Bea and Jarawa were hereditary enemies that had been fighting each other for a long time, probably centuries. It is an odd fact that when the British in 1790 made contact with natives in the region of Port Blair they found one group hostile and another friendly without realizing that they dealt with two entirely different tribes. Lt. Colebrooke even took some friendly natives with him to Calcutta and to the Nicobars. More than a century later M.V. Portman realized that these early "friendlies" had been Jarawa:

On reading Lieutenant Colebrooke's account... it became evident to me that the aborigines with whom the people in Lieutenant Blair's settlement on the South Andaman in 1790 et seq., were friendly,... were members of the South Andaman Jarawa tribe. The description of their habits, weapons and utensils, and the vocabulary given, leaves no room for doubt on this point.The "hostiles" of those early days must have been the Aka-Bea who 70 years later would become the first and closest allies of the British. The colonizing power could not win the friendship of both groups:

A tourist attraction?: Jarawa children on the Andaman Islands/ Photo credit: The Hindu

The disappearance of the Jarawa from the Port Blair region after the 1790s almost certainly is connected with their early contacts to the British. The diseases that a century later would extinguish their hereditary enemies, quite possibly reduced the number of Jarawa and allowed the Aka-Bea to gain the upper hand. As one British administrator wrote:

... how swift the disastrous effects of our relations with the Andamanese have been to them.

Jarawa man using his teeth to peel coconut

Jarawa people

3. JANGIL or RUTLAND JARAWA: This particular Andamanese are extinct. The interior of the large and hilly island of Rutland, lying just off the south coast of Southern Great Andaman, was home to the most obscure of all Andamanese tribes. For reasons that are not entirely clear, Andamanologists do not so much deny this tribe's separate existence as simply ignore it. On the rare occasions when the Rutland-Jarawa or Rutland-Onge are mentioned at all, it is simply assumed that they were ordinary Jarawa resp. Onge. The interchangeability of the terms "Jarawa" and "Onge" during the 19th century and into the 1930s has done nothing to resolve the confusion.

The last time the Jangil tribe of Rutland was officially mentioned was in the Census of India, 1931, where on page 8 it is stated: "In addition there was a fourth clan of Jarawas of which nothing has been seen since 1907."

Andamanese Jarawa women in traditional attire. Anonymous photographer, 1980s

4. SENTINELESE: their population size is now estimated to be 100 to 200. The Sentineli are the quintessential Andamanese: to this day they live their primitive but comfortable and unhurried lives in complete isolation on a small island, they are hostile to all outsiders and they do not wish to change this state of affairs. Violence is the traditional way to ensure the undisturbed enjoyment of their way of life. In the 21st century, they will kill strangers outright and they hide from landing parties that look too strong to fight. If the landing parties offer coconuts and other goods, they will condescend to accept these, but as soon as the feel they have received enough, an obscene gesture makes clear that the outsiders are no longer tolerated and had better leave in a hurry:

Sentinelese relaxing

The effect of the tsunami of December 2004 on North Sentinel island - geographically - was devastating. For maps on how much the little island was geologically affected by the earthquake (see Tsunami Maps - Sentinel island). The coastline of the entire island was change through a massive tectonic uplift! It is a pity that we do not know what the Sentineli themselves make of it all.

Sentinelese youths

As far as can be observed from afar, all this geological uproar did not affect the Sentineli much, nor has it softened their attitude towards meddlesome outsiders. They might have suffered some losses from the tsunami (we do not know) and they might have had food supply and other problems (we do not know either), but they quite obviously adjusted with amazing speed to their re-shaped island and its changed conditions. It is just as well they did since the outside authorities for months after the major event were fully occupied by first getting their act together and then by keeping an Indian population totally unprepared for such a calamity alive and above the water line.The contrast between the "primitive" but adaptable Sentineli and a modern civilization with all its fragile infrastructure was, and still is, astonishing.

Sentinelese boy

Raja Jirake (ca. 1940-2005), chief of the Great Andamanese and his family, shortly before his death on 17 April 2005

(see Obituary)

Jiroki, chief of the 50-strong Great Andamanese tribe who all survived the tsunami. "I am the king. They follow what I say," he said.Photo: AP

Genetic legacy of the Andamanese

The Andamans are theorized to be a key stepping stone in a great coastal migration of humans from Africa.

Africa is the world's second-largest and second most-populous continent, after Asia. At about 30.2 million km? including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of the Earth's total surface area and 20.4% of the total land area....

along the coastal regions of the Indian mainland and towards Southeast AsiaSoutheast Asia

Southeast Asia or Southeastern Asia is a subregion of Asia, consisting of the countries that are geographically south of China, east of India and north of Australia....

, JapanJapan

Japan is an island country in East Asia. Located in the Pacific Ocean, it lies to the east of the Sea of Japan, People's Republic of China, North Korea, South Korea and Russia, stretching from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north to the East China Sea and Taiwan in the south....

and OceaniaOceania

Oceania is a geography, often geopolitics, region consisting of numerous lands—mostly islands in the Pacific Ocean and vicinity. The term "Oceania" was coined in 1831 by French explorer Jules Dumont d'Urville....

. Genetic analysis of the Andamans have included nuclear DNA and haplotype DNA, both such that is inherited through the female line - mitochondrial DNAMitochondrial DNA

Mitochondrial DNA is the DNA located in organelles called mitochondrion. Most other DNA present in eukaryotic organisms is found in the cell nucleus....

and such that is inherited through the male line - Y chromosomes.

Great Andamanese tribe

As to the Y Chromosomes, the Andamanese belong to the lineage which is designated M130 by Wells . This is the lineage that seems to have emigrated from East Africa at least 50,000 years ago along the south coast of Asia eastwards to Australia.

Within this lineage, the Andamanese (Onges and Jarawas) belong almost exclusively to the subtype designated Haplotype D Haplogroup D (Y-DNA)

In human genetics, Haplogroup D is a Y-chromosome haplogroup. Both D and E lineages also exhibit the Single Nucleotide Polymorphism M168 which is present in all Y-chromosome haplogroups except haplogroup A and haplogroup B , as well as the YAP Unique Event Polymorphism, which is unique to Haplogroup DE....

, which is also common in Tibet and Japan, but rare on the Indian mainland. However, this is a subclade of the D haplogroup which has not been seen outside of the Andamans, marking the insularity of these tribes. The only other group that is known to predominantly belong to haplogroup D are the Ainu aboriginal people of Japan. Male Great Andamanese, on the other hand, have a mixed presence of Y-chromosome haplogroups OHaplogroup O (Y-DNA)

In human genetics, Haplogroup O is a Human Y-chromosome DNA haplogroup. Haplogroup O is a close cladistic brother group with Haplogroup N , and is one of several descendants of haplogroup K ....

, LHaplogroup L (Y-DNA)

In human genetics, Haplogroup L is a Human Y-chromosome DNA haplogroup....

, KHaplogroup K (Y-DNA)

In human genetics, Haplogroup K is a Human Y-chromosome DNA haplogroup. This haplogroup is a descendant of Haplogroup IJK . Its major descendant haplogroups are haplogroup L , haplogroup M , Haplogroup NO , haplogroup P , haplogroup S , and haplogroup T ....

and PHaplogroup P (Y-DNA)

In human genetics, Haplogroup P is a Human Y-chromosome DNA haplogroup.This haplogroup contains the patrilineal ancestors of most European ethnic groupss and almost all of the indigenous peoples of the Americas....

, which places them between mainland Indian and Asian populations.

The mitochondrial DNA haplogroup distribution, which indicates maternal descent, confirms the above results. Firstly, all Andamanese belong to the subgroup M which is widely distributed in south Asia, but not found in Africa. Furthermore, they belong to subgroups M2 and M4, which both occur frequently throughout India. On the Andamans, M4 occurs as a subtype known also elsewhere, whereas M2 occurs in two different subgroups which both are unique to the Andamanese, implying a long history on these islands, allowing the time for local genetic development As the lineages M2 and M4 separated 60,000 - 30,000 years ago, and both occur abundantly outside the Andamans, it seems likely that the Andaman islands have been originally colonised not by one single group, but by two different groups, which have kept separate for tens of thousands of years, whereby both lineages have been preserved on the islands up to our days.

The results concerning nuclear DNA stress the uniqueness of the Andamanese people. First, they show a very small genetic variation, indicating that the populations have been isolated for a very long time, and also that they have probably passed through a population bottleneck. Second, there was found one allele among the Jarawas which is found nowhere else in the world. And third, there is no specific affinity to any other population in the world. It is concluded in the article referred to above that they "seem to have remained in isolation for a much longer period than any known ancient population of the world", and thus they are genetically quite unique. The most likely explanation for the observed pattern is probably that the Andamanese are surviving descendants of early migrants having come by boat from Africa and that they have remained isolated in their habitat in the Andaman Islands since their settlement. This is in sharp contrast to the people of the Nicobar islands which are mostly mongoloid immigrants from mainland Asia.

Some anthropologists postulate that Southern India and Southeast Asia was once populated largely by Negritos similar to those of the Andamans, and that some tribal populations in the south of India, such as the IrulasIrulas

Irula is a scheduled tribe of India. Irulas are found in various parts of India, but their main habitat is in the Thiruvallur district of Tamil Nadu....

are remnants of that period.

Other tribes on the Andamans have been eradicated after catching diseases, or have become alcoholics and beggars after coming into contact with outsiders

Picture: RAGHU RAI/MAGNUM PHOTOSThe Andamanese Traditional Society

Social life among traditional Andamanese centred on something called, for want of a better word, the local group. This was a village community, albeit a highly nomadic one. It was in their local group that the Andamanese found peace and a secure place in the world, this was where they felt at home. Membership of a tribe had no practical importance; traditional Andamanese had few if any peaceful dealings with people from outside their own immediate neighbourhood. In most cultures, the family fulfils the emotional and physical functions that in Andamanese society were taken up by the local group. Children were readily adopted away from their parents, descent by blood did not interest anyone much and clans were quite unknown. Children were not expected to show more respect to their parents, real or adopted, than they had to show to all older people. It was age that demanded respect above all else.

Local groups were essentially nomadic, Aryoto somewhat more so than Eremtaga. The groups moved from place to place, wherever the most abundant seasonal food supply could be found, spending only the rainy season in the main camps. Rarely staying at one place outside the main camp for longer than a few weeks, each group remained strictly within its own tiny hunting territory. Any trespassing, let alone poaching, on the land of a neighbouring group would have led to immediate and serious problems. Just how ancient the local groups, their regular trails and campsites could be is shown by the kitchen midden that dot the Andamanese countryside. These are heaps of domestic refuse accumulated when a local group occupied the same site for a period of time year after year for countless generations. The midden are our only source of reliable information about the pre-1858 Andamanese and we shall look more closely at their evidence when we deal with the prehistory of the islands.

Midden were not just piles of domestic refuse that became useful platforms on which to build camps when they had reached a certain size. Their size also reflected the hunting and gathering prowess of the owning group and as such were a source of local pride, serving as a unmistakable markers to the surrounding hunting territory. The symbolic value of a large midden was further strengthened by a link to the group's ancestors by the custom, especially among Onge, to bury their dead or some bones from them under their communal huts, i.e. in the midden. Local pride in their kitchen-midden faded among the Great Andamanese after the 1860s and among Onge after the 1920s with the introduction of the dog. Dogs allowed even the most inept hunter to catch more than enough pigs and made the bow and arrow almost redundant. We find here that helping a primitive group become more efficient can destroy pride in its achievements, undermining the self-confidence necessary for long-term survival.

Beautiful Coastline of the Andamanese Island

The size of local groups has been estimated at between 30 and 50 men, women and children. Each was made up of a few families consisting of father, mother and their unmarried children at the core with unmarried older spinsters and bachelors, widows and widowers and the occasional waif and stray on the fringe. The average group owned a territory of around 40 sq.km (16 sq. miles) while the average tribe consisted of 10 local groups. People were free to leave their own group to take up residence with another and this seems to have been quite a common occurrence. Newly-weds could take up residence wherever they wished: at the local group of the bride or the bridegroom or with any other local group that would accept them. Such movement between friendly local groups was easy but it was normally limited to neighbouring groups. Emigration outside the neighbourhood may have taken place in the old days but must have been rare. A crossing from Aryoto to Eremtaga or across tribal borders would have been unthinkable.

The traditional Andamanese aborigine had a very limited geographical horizon. Members of one group were unaware of the existence of other groups living as little as 30 km (20 miles) away. The ignorance of the traditional Andamanese (apart from the Onge) of their island geography was profound: they knew and cared only about their own hunting grounds and those of their neighbours. The Andamanese seem to have been quite unconscious of being one people and there was no fellow-feeling towards other Andamanese. Quite the contrary, in fact. If a member of one tribe found himself accidentally adrift in his canoe, fetching up on the beach of another tribe, his goose would as surely be cooked as if he had been a shipwrecked British sailor: he would be killed. A feeling of belonging together would only come to the Andamanese after the outsiders and their diseases had cut the ground from under all of them.

The local groups did not have their own names but instead were known by the area they occupied. This could be a major land feature, a hill, a rock, a creek, an island or the name of the main camp-site. For example, a local group of the Aka-Bale tribe living on the island of Teb-juru was known as the Teb-juru-wa, with -wa meaning "people". The northern equivalent of wa was koloko but the system of naming local groups was the same. A local group of the northern Aka-Bo tribe that lived on a creek (buliu) called Terant was known, with irresistible logic, Terant-buliu-koloko. Of 58 place names that could be translated, 39 referred to trees and plants, 12 to topographic features and 7 to socio-cultural aspects. In the old days, it would have been very rare to come across a person from an unknown local group so that the names of local groups became useful only after 1858 when people started to move around and had to identify themselves to strangers.

Several communities at peace with each other and connected by ties of friendship and matrimony, whose members knew and trusted each other and whose ancestors over many generations had done likewise, formed a higher-level grouping, the sept. Social contacts within a sept were frequent and close. Groups met for feasting, dancing and the exchange of gifts, while children were often adopted out to other local groups within the sept where their biological parents could visit them.