DIM CHUKUEMEKA ODUMEGWU-OJUKWU: THE NIGERIAN-BIAFRAN ICONIC WARRIOR AND THE GIANT IKEMBA OF IGBOLAND

"For you (Igbo and Eastern Nigerians), I abandoned all ease and embraced pain. For you I impoverish myself to buy your protection. For you, I walked every battlefront to assure your welfare. For you, I stood when every other person crouched. For you, I endured 13 years of bitter exile. For you, I endured 10 months of maximum security prison. For you, I endured priestly poverty. For you, I continue to struggle...

What I have said is not harsh, it is only the naked truth and it reflect only the intensity of the love I harbour for my people." General Dim Christopher Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu, Ikemba of Nnewi, Dikedioramma, Eze Igbo Gburugburu, Biafran Warlord and a prominent Nigerian politician

General Dim Christopher Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu, Ikemba of Nnewi, Dikedioramma, Eze Igbo Gburugburu, Biafran Warlord and a prominent Nigerian politician

General Dim Christopher Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu (4 November 1933 – 26 November 2011) was the world`s renowned Nigerian military officer and celebrated politician.This gifted orator and a leader was affectionately called Emeka and held the titles Ikemba Nnewi and Eze Igbo Gburugburu for his selfless and dedicated service to his people,Ndi Igbo. The mighty iroko, Ojukwu served as the military governor of the Eastern Region of Nigeria in 1966, the leader of the breakaway Republic of Biafra from 1967 to 1970 and a Nigerian politician from 1983 to 2011, when he died, aged 78. Ikemba Nnewi`s exploits both on the battle and political fields portray him as a restless soul, constantly engaged with the processes aimed at birthing an egalitarian society. He was a man with a most powerful narrative. An essential Nigerian story, with a career compelling in several respects. Ikemba Nnewi was a brave soldier and great thinker!

This great man made his debut into the theatre of life with a silver spoon; into a luxury of a high pedestal; given the best education of our time and had the world at his feet, but chose the road less traveled. He immersed himself in the service of the people. A man of scholastic brilliance from Oxford, Ojukwu chose to serve in the Nigerian military. He will be remembered as a fine officer and a gentleman.

Chief Asiwaju Bola Ahmed Tinubu former Governor of Lagos State and National Leader, Action Congress of Nigeria (ACN)) posits that "after the contributions of our great nationalists such as Nnamdi Azikwe, Chief Obafemi Awolowo and Sir Ahmadu Bello, no single Nigerian has altered the course of Nigeria's history as the late Ikemba Ojukwu. He was forced by the circumstance of history to defend his people when he believed they faced physical and political annihilation. His reasons were clear to his people and his voice and strong determination reverberated across Nigeria. Ultimately, he altered the course of Nigerian political history in profound ways."

Dim Christopher Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu

Ojukwu’s political consciousness evolved very early, and very quickly. As a ten-year old boy in form one at King’s College in Lagos, in 1943, he too had already joined the anti-colonial struggle. That year, he joined senior students like Tony Enahoro (who later became famous Nigerian politician Chief Anthony Enahoro) and Ovie Whiskey among others, to stage an anti-war, anti-colonial protest against the colonial administration, for which some of the students were reprimanded, others conscripted to fight, and from which people like Enahoro emerged into national limelight. Ojukwu was tried as a juvenile in the courts in Lagos for his participation, and two pictures essay that moment: when he lay sleeping at the docks, and when his father, Sir Louis, carries him still sleepy, on his shoulder at the end of proceedings. In 1944, he was briefly imprisoned for assaulting a white British colonial teacher who was humiliating a black woman at King's College in Lagos, an event which generated widespread coverage in local newspapers.

Out of necessity to protect his people and save them from pogrom Odumegwu Ojukwu the brave leader his Ndi-Igbo and Eastern Nigerian people to war against the federal Nigerian government under the military leader Yakubu Gowon in the bid to secede from the federation. Despite losing the war after 3 years and going to exile for 13 years, his people decided to crown him a king in a race that does not believe in the concept of kingship. Yes, Chukwuemeka Odumegwu-Ojukwu was crowned king as the first Eze Igbo Gburugburu. Etymologically, the word gburugburu literally means, “ over all”, which by implication means that his great Igbo brothers and sisters consensually accepted the late fire brand and oracular leader as the over all King of the Igbo. Beside the title of Eze Igbo Gburugburu, the late first Quarter Master General of post-colonial Nigerian Army, also had in his kitty such other titles like; Dikedioranma of Igbo land and Ikemba Nnewi.

Though some Nigerians like Chief Obafemi Awolowo as well as some of his own Igbo people saw Ojukwu`s going to war with the federal government as evil and total mistake, but Dr Osy Ekueme and Dr Ngo Ekwueme disagreed and virtually likened Ojukwu to biblical Moses. In their "Tribute to a Great Man: Dim Chukwuemeka Odumegwu-Ojukwu," Ekwueme&Ekwueme (2012) stated the that Ojukwu "was a ministering angel to Ndi-Igbo. He brought the world's attention to the pogrom against the Igbos by fellow Northern Nigerians. History will have it that he was just like vox clamantis in deserto.. the voice of one shouting in the desert."

The world`s renowned writer, Noble laureate, Yoruba man and proud Nigerian Professor Wole Soyinka who then flew into Biafra to act as a peacemaker and as a result was thrown into jail by the Nigerian President, General Yakubu Gowon posited that Ojukwu`s Ojukwu`s hands were tied and he had to obey the voice of his people to go to war with Nigeria as Chinua Achebe aptly described as "a country desperately cobbled together by British merchants,missionaries and politicians showed signs of its shaky foundations." Soyinka echoed in his tribute to Ikemba Nnewi that "Chukwuemeka Odumegwu-Ojukwu, thrown by Destiny onto that critical moment of truth as a leader, became the voice, the actualising agent of their overwhelming recognition. He heard the answers given by the interrogatory that proceeded from gross human violation, and he responded as became a leader. In so doing, he challenged the pietisms of former colonial masters and the sanctimonousness of much of the world. He challenged an opportunistic construct of nationhood mostly externally imposed, and sought to replace it under the most harrowing circumstances with a vital purpose that answered the purpose of humanity-which is not merely to survive, but to exist in dignity. The world might cavil; the ideologues of undialectical unity might shake their head in dubious appraisal and denounce it as reckless adventurism. This however was his reading, and even the most implacable enemy would hardly deny that his position transcended individual judgment that it rested firmly on the collective will of a people, while they awaited the decisiveness of a responsive leadership."

I must state that even for his bitterest opponents, Ojukwu is known for his discipline, hard work and diplomacy. Daniel Amassoma, President, Ijaw Youth Development Association, said Ojukwu was a leader who believed in equity, justice and fairness. ``Ojukwu was a leader the youth so much believed in; a leader that every follower would always want to follow, till the very end.... we will not be tired, but we shall continue to seek until we are able to get a leader like him.’

Ikemba Nnewi was sentimental, passionate, great lover and jolly romantic man. He married thrice and had several children before he bowed graciously out of this world.

So how did Ikemba Nnewi started his life? It is apparent that Chukwuemeka Odumegwu-Ojukwu was driven by a sense of destiny. He was in any case, a child of destiny. For those who are wont to see something magical and symbolic in coincidences, it is not for nothing that the two greatest leaders from among the Igbo in the 20th century - Nnamdi Azikiwe and Chukwuemeka Odumegwu-Ojukwu - were born in the same month of November, in the same little town, Zungeru. Chukwuemeka "Emeka" Odumegwu-Ojukwu was born on 4 November 1933 at Zungeru in northern Nigeria to Sir Louis Odumegwu Ojukwu, an Igbo businessman from Nnewi, Anambra State in south-eastern Nigeria. Ojukwu was his father`s first son and was born after his parents separation. Sir Louis was in the transport business; he took advantage of the business boom during the Second World War to become one of the richest men in Nigeria. Ojukwu`s personal friend for 15 years Frederick_Forsyth, the world`s celebrated British best-selling novelist and biographer wrote in his biography "Emeka" that "Sir Louis Phillipe Odumegwu-Ojukwu was the wealthiest Nigerian of his generation: a multi-millionaire businessman, who had been chairman of UAC (West Africa), the Nigerian Stock Exchange, director of Shell-BP, had vast investment in property in Lagos, Kano, Port-Harcourt, Enugu, Onistha and other places and owned controlling shares in many of the top blue-chip corporations that still operate in Nigeria today, Emeka Ojukwu could have walked naturally to a life of ease and indolence. In actual fact, by today’s value, Sir Louis Ojukwu’s wealth would be in the range of about ten billion in proper sterling."

Ojukwu started living with his father in Lagos at age 3, and began to climb his educational ladder from his infancy in Lagos, southwestern Nigeria, attending St. Patrick’s School, and CMS Grammar School. At the age of ten he entered form one at King's College in Lagos in 1943. "That year, he joined senior students like Tony Enahoro and Ovie Whiskey among others, to stage an anti-war, anti-colonial protest against the colonial administration, for which some of the students were reprimanded, others conscripted to fight, and from which people like Enahoro emerged into national limelight. Ojukwu was tried as a juvenile in the courts in Lagos for his participation, and two pictures essay that moment: when he lay sleeping at the docks, and when his father, Sir Louis, carries him still sleepy, on his shoulder at the end of proceedings." In 1944, he was briefly imprisoned for assaulting a white British colonial teacher who was humiliating a black woman at his King's College in Lagos, an event which generated widespread coverage in local newspapers.

Sir Louis Ojukwu sensing his son`s radicalism and troubles he was causing in political agitations transferred Emeka to Epsom College, Surrey, England in 1946. Emeka stayed in England for six years excelling in sports-sprinting, rugby, javelin and discus-gaining admission to Lincoln College, Oxford University in 1952. Forsyth (1992) writes "He took BA from Oxford in 1955 and MA both in History having lived a multimillionaire’s son’s life, driving a Rolls Royce, enjoying feminine company, and spending pleasant vacations in Lagos high society." He returned to colonial Nigeria in 1956.

Upon Ojukwu`s return to Nigeria and contrary to Sir Louis’ desire that he join the family business, Ojukwu chose to join the Civil Service, seeking a posting to Northern Nigeria. Due to Nigeria’s federal structure, he was posted instead in 1955 to his native Eastern Region, to Udi as an Assistant District Officer. Udi transformed Ojukwu into an authentic Igbo man! Before then he was a black British gentleman and Lagos boy, who spoke Queens English and fluent Yoruba. According to Forsyth (1992), Ojukwu for the first time, found the land of his ancestors, “I became aware that I was Igbo, and a Nigerian, and an African, and a black man. In that order. And I determined to be proud of all four. In that order.” At Udi, he learnt Igbo language, forsook routine office paperwork in favour of working with villagers and peasants, and learnt the true nature of the African reality. As would later happen with other Igbos, the Udi villagers trusted him and he transcended official colonial administrator, becoming adjudicator and leader. He was subsequently posted to Umuahia and Aba until 1957 and might well have stayed in the civil service, but for his father’s actions. Horrified at Ojukwu’s next posting to Calabar (where he feared that an Efik woman would “capture” his son), Sir Louis deployed his connections with the Governor-General, Sir John Macpherson, who immediately cancelled the transfer.

Evidently Emeka’s choice of the civil service was to craft his own destiny, rather than walk eternally in his father’s wealthy and influential shadows. Frustrated at Sir Louis’ interference in his career, he decided to join the army. Ojukwu joined the military as one of the first and few university graduates to join the army. Ojukwu’s father again tried to prevent him from joining the army as a cadet officer, prompting his joining as a private in 1957! It was only after British military officers recognised the futility and dysfunction of having a Masters from Oxford as a Private in the army with illiterates as contemporaries and superiors that his entry was regularised and his father’s wishes overturned. The other university graduates in the army were O. Olutoye (1956); E. A. Ifeajuna, C. O. Rotimi (1960), and A. Ademoyega (1962).

Emeka Odumegwu-Ojukwu went through training at Teshie in Ghana; Officer Cadet School at Eaton Hall, England from February 1958 for six months; Infantry School at Warminster; Small Arms School at Hythe returning to Nigeria’s Fifth Battalion, Kaduna in November 1958. He was deployed in 1959 to Western Cameroun to join the hunt for rebel Felix Moumi at one point discovering over one million pounds worth of various European currencies which he sent back to Army Headquarters for which he received commendation, but (in early signs of corruption) reportedly never heard of the funds again.

Ojukwu was already in military service at independence in 1960 and wrote in “Because I am Involved” that he “burnt my British passport and turned my back permanently on colonialism and neo-colonialism”; promoted Captain in December 1960; was staff Officer at Army Headquarters from 1961; became Major in summer 1961 (at which point his father reconciled with him); passed Joint Services Staff Course. Ojukwu's background and education guaranteed his promotion to higher ranks. At that time, the Nigerian Military Forces had 250 officers and only 15 were Nigerians. There were 6,400 other ranks, of which 336 were British. After serving in the United Nations’ peacekeeping force in the Congo, under Major General Johnson Thomas Aguiyi-Ironsi, Ojukwu was promoted to Lieutenant-Colonel in January 1963 when he was appointed army Quartermaster-General. In January 1966, when the first military coup happened Emeka Odumegwu-Ojukwu was Commander at the 5th Battalion, Kano.

1966 coup

Lieutenant-Colonel Ojukwu was in Kano, northern Nigeria, when an Igbo army Major Patrick Chukwuma Kaduna Nzeogwu on 15 January 1966 executed and announced the bloody military coup in Kaduna, also in northern Nigeria. Ojukwu as battalion commander in Kano resists Nzeogwu’s end of the coup in the North, an action which leads to the collapse of the Ifeajuna-led coup of January 1966.

The January 1966 coup was led by five majors-Chukwuma Kaduna Nzeogwu, Emmanuel Ifeajuna, Wole Ademoyega, Chris Anuforo and Don Okafor, though there were three other majors (Humphrey Chukwuka, Tim Onwuategwu, John Obienu); five captains (Ben Gbulie, Nwobosi, Oji, Ude and Adeleke); four lieutenants (Ezedigbo, Okaka, Oguchi and Oyewole) and seven 2-Lietenants involved. Overall leadership and conceptualisation may be attributed to Nzeogwu and Ifeajuna. Nzeogwu was a first-class, Sandhurst-trained soldier, a radical, courageous, anti-colonial and revolutionary officer who had become disillusioned with the direction of the emerging Nigerian nation, and a nationalist and patriot, who appeared incapable of tribalism and other parochial thinking. Ifeajuna had revolutionary ideas, but was a less-predictable person.

In this coup different actors were given roles to eliminate certain political targets.Nzeogwu’s single-mindedness and dedication accounted for success of the plotters in eliminating their Hausa/Fulani targets in Kaduna and Lagos while Ifeajuna and cohorts failed to eliminate Igbo targets such as Army GOC General Aguiyi-Ironsi, Eastern Premier Dr Okpara and Dr Nnamdi Azikiwe. At the end of the coup, the prime minister, Tafawa Balewa, Northern Premier Ahmadu Bello; and Northern officers-Brigadier Maimalari, Colonel Kur Mohammed, Lt.Colonels Abogo Largema, and Yakubu Pam had been killed. The largely politically illegitimate Western Premier S.L.A Akintola, Ademulegun and Shodeinde were also killed. All Igbo political and military targets had somehow escaped except for Lt.Colonel Arthur Unegbe. It wasn’t long before the coup was transformed in the minds particularly of Northerners into an Igbo attempt to wipe away their political and military leaders and the counter-coup of July 1966 which brought Yakubu Gowon (and the North) back to power became inevitable.

Gen. Ironsi watching a mortar concentration at Kachia near Kaduna in 1966, shortly before his overthrow and assassination. L-R: Lt. Col. Imo, Major Obioha, Lt. Col Okoro (with umbrella), Lt. Col. A. Madiebo, Major Ogbemudia (with map), Col. Wellington Bassey, Maj. Gen. A. Ironsi, Lt. Col. O. Kalu, Lt. Col. M. Shuwa, Lt. Col. J. Akagha etc.

In all this Ojukwu was loyal army servant and never involved himself in the putsch. Lt. Col Emeka Odumegwu-Ojukwu then, Brigade Commander in Kano was never consulted by the plotters probably because they saw him as a pro-establishment officer who was unlikely to sympathise with their plans, and because he was senior to all the coup plotters. There is no dispute over the fact that as the actual coup unfolded, Ojukwu absolutely refused to cooperate with Nzeogwu in Kaduna and the other plotters. Rather he rallied and kept his troops loyal to the federal government. He also protected Northern citizens including his friend, Emir of Kano, Ado Bayero during the period of uncertainty after the coup attempt. Indeed Ojukwu’s appointment as military governor of the Eastern Region was a clear acknowledgment of his loyalty to the nation and army authorities. It is indeed an irony that it was this same pro-establishment, nationalist and loyalist officer who would soon lead the Biafran rebellion against Nigeria! It is clear that circumstances thrust this role upon Ojukwu and he merely accepted the role history had earmarked for him.

Aguiyi-Ironsi took over the leadership of the country and thus became the first military head of state. On Monday, 17 January 1966, he appointed military governors for the four regions. Lt. Col. Odumegwu-Ojukwu was appointed Military Governor of Eastern Region. Others were: Lt.-Cols Hassan Usman Katsina (North), Francis Adekunle Fajuyi (West), and David Akpode Ejoor (Mid West). These men formed the Supreme Military Council with Brigadier B.A.O Ogundipe, Chief of Staff, Supreme Headquarters, Lt. Col. Yakubu Gowon, Chief of Staff Army HQ, Commodore J. E. A. Wey, Head of Nigerian Navy, Lt. Col. George T. Kurubo, Head of Air Force, Col. Sittu Alao.

In May 1966, riots and a bloodbath erupted in the North with at least 3,000 Easterners killed, and others fleeing South. This presented problems for Odumegwu Ojukwu. He did everything in his power to prevent reprisals. As a Governor of the Eastern Region since January 1966, he pleaded with Igbos to return up North and in June 1966, barely a month after the massacre, he appointed his old friend, Emir of Kano, Chancellor of the University of Nigeria.

On 29 July 1966, a group of officers, including Majors Murtala Muhammed, Theophilus Yakubu Danjuma, and Martin Adamu, led the majority Northern soldiers in a mutiny that later developed into a "counter-coup" or revenge coup. The coup failed in the South-Eastern part of Nigeria where Ojukwu was the military Governor, due to the effort of the brigade commander and hesitation of northern officers stationed in the region (partly due to the mutiny leaders in the East being Northern whilst being surrounded by a large Eastern population). The initial objective of the Northern officers who led the coup (Murtala Muhammed, Yakubu Gowon, Theophilus Danjuma, et al) appeared clearly to be secession (“araba” – separation in Hausa) from Nigeria until they were reportedly persuaded by the British High Commissioner that “you’ve got it all now; why settle for half” and Gowon became Head of State, leading to Ojukwu’s first disagreement with the Northern military establishment.

In the coup, the Supreme Commander General Aguiyi-Ironsi and his host Colonel Fajuyi were abducted and killed in Ibadan. On acknowledging Ironsi's death, Ojukwu insisted that the military hierarchy be preserved. In that case, the most senior army officer after Ironsi was Brigadier Babafemi Ogundipe, should take over leadership, not Colonel Gowon (the coup plotters choice), however the leaders of the counter-coup insisted that Colonel Gowon be made head of state. Both Gowon and Ojukwu were of the same rank in the Nigeria Army then (Lt. Colonel). Ogundipe could not muster enough force in Lagos to establish his authority as soldiers (Guard Battalion) available to him were under Joseph Nanven Garba who was part of the coup, it was this realisation that led Ogundipe to opt out and accepted posting as High Commissioner to the United Kingdom. Thus, Ojukwu's insistence could not be enforced by Ogundipe unless the coup plotters agreed (which they did not). The fall out from this led to a stand off between Ojukwu and Gowon leading to the sequence of events that resulted in the Nigerian civil war.

Many Eastern/Igbo officers had been killed during the July counter-coup, evidently as collateral revenge for the earlier deaths in January. In September 1966, a second pogrom commenced with large scale killings everywhere across Northern Nigeria. After Gowon’s broadcast on September 29, rather than abate, the killings intensified. Pain, anger and rage were felt across the East, especially by Ojukwu who, to his eternal regret, had urged those who fled in May to return, many to their brutal end. Ojukwu started resisting Federal army`s pogrom on Easterners and Igbos. It must be noted here that the first threat of force was issued by Gowon on 30/11/66 and the first shells were fired on 6/7/67 by the “federal” side

In January 1967, the Nigerian military leadership went to Aburi, Ghana for a peace conference hosted by the Ghanaian head of state General Joseph Ankrah. In Aburi, Ojukwu proposed the foundational thesis for the evolution of a modern Nigerian state under clear federal principles. The Aburi agreement, meant to resolve the crisis and was freely signed by all parties under General Ankrah’s auspices, was unilaterally rejected by Gowon upon pressure from his British minders and their agents in the Nigerian civil service, and levies war against the East, when he return to Lagos on 26/1/67 upon. The accord established equal, federal control over the armed forces through the Supreme Military Council (SMC); a military HQ with equal regional representation; regional military area commands; major national appointments – diplomatic, senior armed forces and police, and “super-scale” federal civil service and corporations – would be made by the SMC. In effect, Ojukwu’s quest was equality of federating regions and rejection of hegemony. Unceasing calls for “true federalism”, “zoning”, “rotation”, “federal character”, “non-marginalisation”, etc., show that Ojukwu’s position was prescient.

On 30 May 1967,as a result of this, Colonel Odumegwu-Ojukwu declared Eastern Nigeria a sovereign state to be known as BIAFRA:

"Having mandated me to proclaim on your behalf, and in your name, that Eastern Nigeria be a sovereign independent Republic, now, therefore I, Lieutenant Colonel Chukwuemeka Odumegwu-Ojukwu, Military Governor of Eastern Nigeria, by virtue of the authority, and pursuant to the principles recited above, do hereby solemnly proclaim that the territory and region known as and called Eastern Nigeria together with her continental shelf and territorial waters, shall, henceforth, be an independent sovereign state of the name and title of The Republic of Biafra."

(No Place To Hide – Crises And Conflicts Inside Biafra, Benard Odogwu, 1985, Pp. 3 & 4).

Biafran (Nigerian Civil) War

On 6 July 1967, Gowon declared war and attacked Biafra. For 30 months, the war raged on. Now General Odumegwu-Ojukwu knew that the odds against the new republic were overwhelming. Most European states recognised the illegitimacy of the Nigerian military rule and banned all future supplies of arms, but the UK government substantially increased its supplies, even sending British Army and Royal Air Force advisors. The British watached on unconcerned as humanitarian and food aid to the Biafran enclave was stopped. The Nigerian government tried to starve out the rebels. Chief Obafemi Awolowo, then a minister, said in 1968 “all is fair in war and starvation is one of the weapons of war. I don’t see why we should feed our enemies fat in order for them to fight us harder.”

During the war in addition to the Aburi (Ghana) Accord that tried to avoid the war, there was also the Niamey (Niger Republic) Peace Conference under President Hamani Diori (1968) and the OAU sponsored Addis Ababa (Ethiopia) Conference (1968) under the Chairmanship of Emperor Haile Selassie. This was the final effort by General Ojukwu and General Gowon to settle the conflict at the Conference Table. The rest is history and even though General Gowon, a good man, promised "No Victor, No Vanquished," the Igbos were not only defeated but felt vanquished.

After three years of non-stop fighting and starvation, a hole did appear in the Biafran front lines and this was exploited by the Nigerian military. As it became obvious that all was lost, Ojukwu was convinced to leave the country to avoid his certain assassination. On 9 January 1970, General Odumegwu-Ojukwu handed over power to his second in command, Chief of General Staff Major-General Philip Effiong, and left for Côte d'Ivoire, where President Felix Houphöet-Biogny – who had recognised Biafra on 14 May 1968 – granted him political asylum.

Death of the Biafran mercenary Marc Goosens in an attack on Onitsha, which was dramatically captured on film

There was one controversial issue during the Biafra war, the killing of some members of the July 1966 alleged coup plot and Major Victor Banjo. They were executed for alleged treason with the approval of Ojukwu, the Biafran Supreme commander. Major Ifejuna was one of those executed. More or so, there was a mystery on how Nzeogwu died in Biafra enclaved while doing a raid against Nigeria army on behalf of Biafra.

In all on could decipher that Ojukwu fights to protect the lives of his threatened people, and in the interval, creates what may possibly have been the most advanced, most progressive modern state in Africa. The evidence of administrative efficiency was there in the way Ojukwu mobilized the civil and bureaucratic structures of the East in Biafra.

Sustaining the Biafran war

Blockaded by air, land and sea, Ojukwu and Biafra refined enough fuel stored under the canopies of jungle trees in the town of Obohia in Mbaise, Imo State Nigeria. These were the products of makeshift Refineries that moved from place to place as the enclave receded. Facing deadly air raids from Russian MIG jets piloted by Algerian and Egyptian mercenaries, Ojukwu's Biafra and University scientists designed, collected resources, and build the "Ogbunigwe," a series of large bombs, in only a matter of weeks. As the drums of war were sounding, Ojukwu's Biafra was planning the establishment of the University of Science and Technology in Port-Harcourt.

Ojokwu`s Biafra had counted on USSR support but they were let down. The retired Supreme Court Judge, Paul Nwokedi has recounted the premise for which the Soviet Union refused to support "a young nation seeking self-determination" when as Ojukwu’s envoy to Moscow he asked the same questions. Andre Gromyko’s, response to him was instructive: "Pauliya, Europe will not let you go…you have not fought this war for one year and you’re already producing your own rockets and rocket fuel…" he said to Nwokedi in 1968. That comment is a tribute to the visionary leadership of Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu.

Biafran Development

Biafran technicians conceived and produced the Ogbunigwe, a cone shaped, sometimes cylindrical cluster bomb that disperses shrapnel with percussion. It was also used as a ground to ground and ground to air projectile and was used with telling and destructive effect.

Ojukwu and the Biafra RAP built airports and roads, refined petroleum, chemicals and materials, designed and built light and heavy equipment, researched on chemical and biological weapons, rocketry and guidance systems, invented new forms of explosives, tried new forms of food processing and technology.

Biafra home-made armoured vehicle the "Red Devil," celebrated also in the book by Sebastian Okechukwu Mezu Behind The Rising Sun, was a red terror in the battle field. The Biafra shoreline was lined with home-made shore batteries and remote controlled weapons systems propelling rockets and bombs.

The famous photo that heralded the armistice and official end of the Nigerian civil war in the newsmedia in January 1970: federal troops celebrating while running on the Uli air strip that had been the final foothold of the secessionists, and from where rebel leader Ojukwu fled into exile in Cote D'Ivoire

After Biafra

After 13 years in exile, the Federal Government of Nigeria under President Shehu Aliyu Usman Shagari granted an official pardon to Odumegwu-Ojukwu and opened the road for a triumphant return in 1982. The people of Nnewi gave him the now very famous chieftaincy title of Ikemba (Strength of the Nation, while the entire Igbo nation took to calling him Dikedioramma ("beloved hero of the masses") during his living arrangement in his family home in Nnewi, Anambra.

His foray into politics was disappointing to many, who wanted him to stay above the fray. The ruling party, NPN, rigged him out of the senate seat, which was purportedly lost to a relatively little known state commissioner in then Governor Jim Nwobodo's cabinet called Dr. Edwin Onwudiwe.

Following these events some of Ojukwu`s critics argued that Ojukwu engaged in "self-demystification" after remaining an enigmatic myth. In his defense for re-entering politics, Chinua Achebe writes "A man of lesser stature may have chosen to disappear from public view and engagements. Not Ikemba! He decided that being a shy Nigerian was out of the question. Regardless of the occasional taunts he received from various corners of Nigeria-including from among some of his own people-he rolled up his sleeves and offered himself as a labourer in Nigeria’s vineyard. He knew more than many, the steep price that millions had paid for the prospects of founding a Nigerian nation. He knew too that Nigeria remained an unfounded idea, that it was caught in the cycle of lost opportunities, of promising roads not taken .Above all, he knew the risks involved in partisan politics ,but would rather take the risks than remain a spectator in the process that shaped the lives of his people." Ojukwu has himself argued that he does not want to be a "myth" when there is so much work to be done. This is an act of courage.

The second Republic was truncated on 31 December 1983 by Major-General Muhammadu Buhari, supported by General Ibrahim Badamosi Babangida and Brigadier Sani Abacha. The junta proceeded to arrest and to keep Ojukwu in Kirikiri Maximum Security Prison, Lagos, alongside most prominent politicians of that era. Having never been charged with any crimes, he was unconditionally released from detention on 1 October 1984, alongside 249 other politicians of that era—former Ministers Adamu Ciroma and Maitama Sule were also on that batch of released politicians. In ordering his release, the Head of State, General Buhari said inter alia: "While we will not hesitate to send those found with cases to answer before the special military tribunal, no person will be kept in detention a-day longer than necessary if investigations have not so far incriminated him." (WEST AFRICA, 8 October 1984)

After the ordeal in Buhari's prisons, Dim Odumegwu-Ojukwu continued to play major roles in the advancement of the Igbo nation in a democracy because

"As a committed democrat, every single day under an un-elected government hurts me. The citizens of this country are mature enough to make their own choices, just as they have the right to make their own mistakes".

Ojukwu had played a significant role in Nigeria's return to democracy since 1999 (the fourth Republic). He had contested as presidential candidate of his party, All Progressives Grand Alliance (APGA)for the last three of the four elections. Until his illness, he remained the party leader. The party was in control of two states in and largely influential amongst the igbo ethnic area of Nigeria.

Left-Governor Obi(Anambra State),Odumegwu-Ojukwu,his wife ,Bianca.I call him-'The man who saw tomorrow'.

Ojukwu`s Married life

Ojukwu the warrior and a giant of a man was a known socialite. He is well-known for partying big-time and also surrender himself with beautiful women. However, in 1965, Ojukwu married his wife, then the 19 year old devorcee Mrs. Njideka Ojukwu (Aunty Njideka).

Sonny Okosun, Ojukwu, and Christie Essien Igbokwe

When Njideka got married to the legendary Ikemba Nnewi, she had separated from her first husband Dr Brodie Mends, a Ghanaian Fante surgeon. She married Brodie-Mends in 1955 and gave birth to her first and only daughter, Iruaku, in 1956. After marrying Ojukwu in 1962 they move from Lagos to Kano in 1965 where her husband was staying. The marriage was celebrated at Apapa, Lagos with reception at Sir Odumegwu’s Ikoyi residence. Aunty Njideka was said to be a very brave woman who stood by Ikemba Nnewi throughout the entire civil war. Phillip Effiong jr, son of Ojukwu’s second in command in the Biafran army, Gen Phillip Effiong, "Mrs. Njideka Ojukwu is one of Biafra’s Unsung “Sheroes" of Biafran war. Mrs Njideka Ojukwu and mother to the former Anambra State Commissioner for Special Duties and Transport, Mr. Emeka Odumegwu Ojukwu.

After divorcing Aunty Njideka, Ikemba married another beautiful woman, Stella Onyeador. The marriage went on for sometime and ended in a divorce.

After this Ojukwu got involved with the 20 years old Bianca, "the most beautiful woman in Nigeria" in 1989. Their relationship went on for some years they got married formally on November 12, 1994.

Bianca Ojukwu the third wife of Ikemba

The will listed Ojukwu's children as follows: Tenny Hamman (daughter), Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu Jnr (son), Mmegha (Mimi) (daughter), Okigbo (son), Ebele (daughter), Chineme (daughter), Afam (son) and Nwachukwu (son). Of his Children, Tenny was never known until Ojukwu`s death when his will made mentioned of this secret daughter.

Death

On 26 November 2011, Ikemba Odumegwu Ojukwu died in the United Kingdom after a brief illness, aged 78. His death was an instant international news as all the most powerful media outlets in the world carried the sad news. Tributes pour in from from the fore-corners of the world showing Ikemba`s international popularity and fame.

The Nigerian army accorded him the highest military accolade and conducted funeral parade for him in Abuja, Nigeria on 27 February 2012, the day his body was flown back to Nigeria from London before his burial on Friday, 2 March. He was buried in a newly built mausoleum in his compound at Nnewi.

Before his final interment, he had about the most unique and elaborate weeklong funeral ceremonies in Nigeria besides Chief Obafemi Awolowo, whereby his body was carried around the five Eastern states, Imo, Abia, Enugu, Ebonyi, Anambra, including the nation's capital, Abuja. Memorial services and public events were also held in his honour in several places across Nigeria, including Lagos and Niger state his birthplace.

DIM CHUKWUEMEKA ODUMEGWU-OJUKWU'S BURIAL IN NNEWI FROM LEFT: FIRST LADY, DAME PATIENCE JONATHAN; PRESIDENT GOODLUCK JONATHAN; SON OF THE LATE DIM CHUKWUEMEKA ODUMEGWU-OJUKWU, EMEKA JNR, AND GOV. PETER OBI OF ANAMBRA, AT THE BURIAL OF DIM CHUKWUEMEKA ODUMEGWU-OJUKWU AT NNEWI, ANAMBRA, ON FRIDAY (2/3/12). NAN

His funeral was attended by President Goodluck Jonathan of Nigeria and ex President Jerry Rawlings of Ghana among other personalities.

ex President Jerry Rawlings of Ghana PAYING HIS LAST RESPECT TO iKEMBA

"President Jonathan said that the achievements that set Ojukwu apart and which had made him subject of “edifying posthumous commentaries”, though undeniably solid were far from personal. “They were solid altruistic achievements of a man whose life epitomized love and self sacrifice.

High ranking military officers and pall bearers carry the coffin of Nigeria's secessionist leader Odumegwu Ojukwu during the national inter-denominational funeral rites at Michael Opkara Square in Enugu, southeastern Nigeria

For only such love could explain his preference for the great risk involved in the leadership role he assumed in his lifetime to the privileged background into which he was born,” he said. Recalling how Ojukwu sailed to leadership limelight and how “he reluctantly accepted the role that perhaps most critically defined his place in the history of our country”, the president also noted how the late Biafran leader, “despite his reluctances, he acquitted himself quite historically, heroically while fulfilling that role, not withstanding the difficult odds that stood against his side” during the civil war.

“We are also aware of how after the dust of hostilities had settled, he became strong advocate of a united Nigeria. All these governed by the same ideals of justice and fairness to all which were the hallmark of his vision as a patriot of humanists,” the president said."

Ikemba of Nnewi was a special soul born to fulfill a special role. He was no angel but he was a great leader and even his opponents cannot deny him that. Chinua Achebe put it aptly that he "was a rare masquerade, the kind that appears once in a generation among a people."

Former Secretary of the Commonwealth Emeka Anyaoku (L) sits with the Nobel Laureate Wole Soyinka during the national funeral ceremony for Biafran ex-warlord Lieutenant Colonel Odumegwu Ojukwu in Nigeria's southeastern city of Enugu

For some Igbos who criticized him unfairly over the creation of independent state of BIAFRA and subsequent civil war that ensued leading to the death of over 3 million Igbos and Easterners, Ikemba poured out his heart and told them the naked truth that "For conferring these titles on him, Ojuku had this to say:""For you (Igbo and Eastern Nigerians), I abandoned all ease and embraced pain. For you I impoverish myself to buy your protection. For you, I walked every battlefront to assure your welfare. For you, I stood when every other person crouched. For you, I endured 13 years of bitter exile. For you, I endured 10 months of maximum security prison. For you, I endured priestly poverty. For you, I continue to struggle...

What I have said is not harsh, it is only the naked truth and it reflect only the intensity of the love I harbour for my people." Clearly one can see from his speech here that It takes Ikemba like Odumegwu Ojukwu of nnewi to be Ikemba.

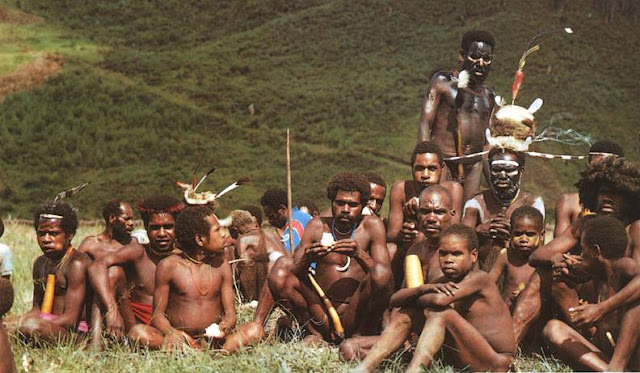

Ndi Igbo performing Ohafia War dance at Ikemba Nnewi`s funeral

In his last speech to the Igbo people whilst addressing the meeting of South East Elders and Leaders held in Owerri on the 5th of March, 2010 (just before the stroke), he insisted that Ndi-Igbo should continue to act as the adhesive force holding the Nigerian fabric together. He stated "Ndigbo are nation-builders not nation-wreckers, but that the strong Igbo moral sense, handed down to us by our ancestors, will always resent and rebel against injustice, inequity and mindless blood-letting." ...........he " exhorted Ndigbo to be assertive and courageous in protecting their rights, lives and properties as bona fide citizens of Nigeria whilst respecting the rights of other citizens."

Ojukwu like Robert Green Ingersoll said of his late brother, "This brave and tender man in every storm of life was oak and rock, but in the sunshine he was vine and flower. He was the friend of all heroic souls. He climbed the heights and left all superstitions far below, while on his forehead fell the golden dawning of the grander day".

When Edward Snowdon interviewed him and Wole Soyinka and Achinua Achebe before his death weather he would have done different thing if the circumstances that led to the civil war should crop up, Ikemba the who saw yesterday replied "“History does not repeat itself,” he growled. “But if it did, I would do exactly the same again. Excuse me.”

Yet Ojukwu's life and times were not defined by his cosmopolitan appeal, though he was no rustic; nor was he defined by flaming Nigerian nationalism, though many would insist, with more facts on the tragic Nigerian Civil War (1967-1970), that he was a rebel with a cause. He was rather defined by Igbo nationalism, if not irredentism. But given the turn of events in Nigeria, with its continuous crisis of nationhood and identity, neither Igbo nationalism nor Igbo irredentism would appear illegitimate. (Asiwaju Bola Ahmed Tinubu

Former Governor of Lagos State and National Leader, Action Congress of Nigeria (ACN))

Source:http://www.businessdayonline.com/NG/index.php/analysis/columnists/33696-ojukwu-and-nigerian-federalism-3

OJUKWU: A GIANT WHO LIVED FOR OTHERS

Being a tribute to Ojukwu taken from Pages 23-26 of the Book of Tribute-Life and times of Dim Chukwuemeka Odumegwu-Ojukwu

By Professor Chinua Achebe

There is a cruel irony in the coincidence between the death of Ikemba Nnewi, Chukwuemeka Odumegwu-Ojukwu (1933-2011) and a disturbing surge in sectarian violence in Nigeria. Ojukwu’s life, career, and abiding commitments were shaped by just such trying circumstances as Nigeria faces today. That his death and funeral

are framed by the familiar circumstances that he fought against four decades ago clearly projects the significance of his life and the unsolved challenges confronting our dear homeland. A beleaguered nation sorely needs Ikemba’s voice at this juncture to caution our feet against treading the path of thunder.

And even in death his voice rings clear, as urgent and resonant as perhaps only he had the ability, bearing the message of restraint, justice and restitution.

This giant of a man may now lie inert, but his intrepid voice speaks to all of us from the grave. We should listen and hearken to the message that issues from him. The question is: Are we ready to listen?

Or are we like the proverbial housefly devoid of counsel that journeys with the corpse into the grave?

I have called Ojukwu a giant of a man, and I know there are people ready to challenge the praise.

Even so, I am confident that in death, his stature and the scale of his achievements will rise above the malice and scepticism of his traducers. Why do I think he was a giant?

One mark of greatness lies in how a man or woman responds to onerous historical challenges and how his or her ideas and vision endure over time. Ojukwu was barely 32 when history thrust him onto the stage of great

convulsions.Nigera, a country desperately cobbled together by British merchants,missionaries and politicians [/b]showed signs of its shaky foundations. Bitter regional and sectarian rivalries and resentments had combined with corruption and rigged elections to bring the fledging nation to a jagged edge. After several waves of ethnic cleansing of southeasterners, there was little doubt that the idea of one Nigeria was strained beyond forced amalgamation.

When embattled easterners demanded self-determination, Ojukwu displayed true greatness by accepting –and quickly rising-to the challenge of leadership. In proclaiming his people’s choice to live as a separate national entity called Biafra,he bravely entered a territory that was for the most part uncharted. True, he had read history at Oxford, but he had no history of secession in Africa to go by. He and Biafra had no models.

Ojukwu’s Biafra was, then an experiment in the best sense of that word. Along with the confident, self-posessed, but never pompous man who led us, we had to learn every lesson about the dim prospects and huge frustrations of founding a nation, as we went along. Even so, through the sheer eloquence of his representation of the plight of his people, the passion and charisma he brought to the Biafran cause, and his powers of engagement with Biafrans and others,Ojukwu found a way to stamp the Biafran struggle in the world’s consciousness ,to elevate his people’s struggle onto the international platform.

Much of the grit,inventive genius and resilience of the Biafran people owed to Ojukwu’s inspiring leadership. For a child of uncommon privilege-his father Sir Louis Odumegwu Ojukwu was once Nigeria’s towering

businessman-he exuded a common touch and infectious charm and empathy that galvanised Biafrans and many supporters around the world. His cosmopolitan background-born of Igbo parents in Zungeru, Northern Nigeria, experienced adolescence as a student in Kings College, Lagos, South Western Nigeria, and studied abroad-was an asset that defined his engagement with the world. If he soared above other public figures in Nigeria and is so well celebrated, it was partly because of his disdain for the culture of wanton accumulation at the expense of the people. Instead he made self-disregarding sacrifices as the leader of an economically strapped Biafra.

The "Biafran" Cabinet at a Church service, on the extreme right is the late Sir Louis Mbanefo- former Supreme Court Judge and Judge of the World Court, who severally advised Ojukwu to negotiate a dignified end- to no avail and who was then left - alongside Phillip Effiong to negotiate surrender, after Ojukwu took off.

Ojukwu always insisted, rightly, that the fact that Biafra ultimately buckled should not be read as a sign that the cause itself was misconceived. He was adamant that the quest for Biafra- as a quest for justice

and equity –lives on and will continue to reverberate in Nigeria and elsewhere.

He made point of rebuking Nigeria for behaving all too frequently as if it had not fought a war. True to Ikemba’s vision, forty years after the war, Nigerians from various regions have continued to agitate for a sovereign national conference to determine the structure and terms of a federal union.

Another measure of Ojukwu’s greatness can be glimpsed from his deportment once he returned to Nigeria, after a prolonged exile in Cote D’Ivoire.

A man of lesser stature may have chosen to disappear from public view and engagements. Not Ikemba! He decided that being a shy Nigerian was out of the question. Regardless of the occasional taunts he received from various corners of Nigeria-including from among some of his own people-he rolled up his sleeves and offered himself as a labourer in Nigeria’s vineyard. He knew more than many, the steep price that millions had paid for the prospects of founding a Nigerian nation. He knew too that Nigeria remained an unfounded idea, that it was caught in the cycle of lost opportunities, of promising roads not taken .Above all, he knew the risks involved in partisan politics ,but would rather take the risks than remain a spectator in the process that shaped the lives of his people.

In death, his voice has understandably become louder. Like a venerable ancestor, that he is, he has much to teach us about the negotiations and investments we must make in order to dispel the dark clouds that are

looming over us, especially at this dangerous chapter in our history. If we listen,we can still usher in the long-dreamed achievement of our collective aspirations.[b] A man like Ojukwu was a rare masquerade, the kind that appears once in a generation among a people.

May his soul rest in perfect peace.

Chinua Achebe was a former professor n David and Marrianna Fisher University and Professor of African Studies at Brown University,Providence, USA. He is well-known for his Novel "Things Fall Apart."

By Wole Soyinka

Culled from "Book of Tributes-life and times of Dim Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu"

"Having mandated me to proclaim on your behalf and in your name, that Eastern Nigeria be a sovereign Independent Republic, now therefore, I Lieutenant Colonel Chukwuemeka Odumegwu-Ojukwu, Military Governor of Eastern Nigeria, by virtue of the authority, and pursuant to the principles recited above, do hereby solemnly proclaim that the territory and region known as and called EASTERN Nigeria, together with her continental shelf and territorial waters shall henceforth be an independent sovereign state, of the name and title Republic of Biafra"

With these words, on May 30 of the year 1967, a young bearded man, thirty-four years of age in a fledgling nation that was barely seven years old, plunged that nation into hitherto uncharted waters, and inserted a battalion of question marks into the presumptions of nation-being on more levels than one. That declaration was not merely historic, it re-wrote the more familiar trajectories of colonialism, even as it implicitly served notice on the sacrosanct order of imperial givens. It moved the unarticulated question, when is a nation? away from simplistic political parameters-away from mere nomenclature and habitude – to the more critical area of morality and internal obligations.

It served notice on the conscience of the world, ripped apart the hollow claims of inheritance and replaced them with the hitherto subordinate yet logical assertiveness of a people`s will. Young and old, the literate and the uneducated; urban sophisticates and rural dwellers, citizen and soldier-all were compelled to re-examine their own situating in a world of close inter-relations and distant ideological blocs, bringing many to that basic question :Just when is a nation?

Throughout world history, many have died for, but without an awareness of the existential centrality of that question. The Biafran act of secession was one that could claim that its people had direct and absolute intimacy with the negative corollary of that question. Their brutal, immediately antecedent circumstances ensured that they could provide one of more truthful and urgent answers to the obverse of that question, which would then read: when is a nation not?

Chukwuemeka Odumegwu-Ojukwu, thrown by Destiny onto that critical moment of truth as a leader, became the voice, the actualising agent of their overwhelming recognition. He heard the answers given by the interrogatory that proceeded from gross human violation, and he responded as became a leader. In so doing, he challenged the pietisms of former colonial masters and the sanctimonoussness of much of the world. He challenged an opportunistic contruct of nationhood mostly externally imposed, and sought to replace it under the most harrowing circumstances with a vital purpose that answered the purpose of humanity-which is not merely to survive, but to exist in dignity. The world might cavil; the ideologues of undialectical unity might shake their head in dubious appraisal and denounce it as reckless adventurism. This however was his reading, and even the most implacable enemy would hardly deny that his position transcended individual judgment that it rested firmly on the collective will of a people, while they awaited the decisiveness of a responsive leadership.

Even today, many will admit that, in this very nation, that question remains unresolved; that more and more people are probing that question; that all over the world, certainly in our own continent, multitudes are braving impossible odds, conceding immense sacrifice to contest the facile and complacent answer that whatever is, is divinely ordained, thus conferring the mantle of divinity to those whose spatial contrivances called nations continue to creak at the seams and consume human lives in millions.

Their mission is to conserve a sacrosanct order that was ever given human legitimacy as if it is not the very humanity that grants authority to the cohesion of any inert piece of real estate and thus, only such humanity contains, and can exercise a moral will in designating it a habitable and productive entity that truly deserves the designation of nation-being.

Humanity must be allowed to make its errors. Indeed errors are the unregistered provisions in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. There are however degrees and qualities of errors, and the most lamentable are those that proceed from the lack of courage to interrogate whatever humanity has merely happened upon, or has been imposed upon us as thinking humans, and failure to accept the resultant clamour and the antecedents of this clamour for change. This is what constitutes a primal error, a deficiency in responsive capabilities, a condition of mental enslavement.

Change is not an absolute however, but I acknowledged it to be the product of human curiosity, observation, creativity and transformative intelligence. Nor should change imply ,of necessity, the destruction of what is viable, what amplifies the value that already make us human, or bind us in the common pursuit of the amelioration of existence. Where stagnation, retrogression, or diminution of those very virtues, those very progressive qualities that make even self-fulfilment possible stare a people in the face however then, surely the iterative of change becomes irresistible and its horizons exert the pressure of inevitability. That immense call fell on the shoulders of our comrade Chukwuemeka, and he responded in the manner we all know, for better or for ill, but he was not found wanting in the hour of decision.

The error of Biafra is what we hear plenty of. Only rarely with dismissive condescension, are rightly attributed, those achievements against overwhelming odds that gave rise to that ancient adage: Necessity is the mother of invention, or even, Sweet are the uses of adversity. There were indeed cruelties here also, on Biafran soil, as on her opposing side, and there were needless prolongation of human suffering. Biafra became a byword for paranoia. There were politics that dug Biafra deeper and deeper into its self-dug bunker, from where the world became a blank surrounding, closing in despite apertures that were clearly visible to many, even from within.

A leader must accept responsibility for all such failings, with perhaps the meagre consolation that throughout the history of conflicts and especially of conflicts based on the righteous perception of wrongs; such has been the fate of the beleaguered. But it would be a greater injustice from all of us if we fail in the apportionment of the positive ,such as an inspirational leadership that held a people together and aroused an unprecedented level of creative adjustments, of practical inventiveness ,the like of which has yet to be recorded on our continent. What a pity that policy and suspicion has led to the squandering of such bequests!

The regrets, individual and collective, the triumph of the dominance of human spirit, no longer matter to the man whose passage among us we are gathered here to commemorate any more than the very questioning structures of human co-habitation. He who lived to embrace, to share bread and salt with his once implacable enemies, is no longer with us, yet he remains among us. In his lifetime, bitterness did turn so many pages towards the chapter of reconciliation, but has it truly brought mutual understanding?

Let us reflect on that question carefully today-yes a full half century later- as we bid farewell to one who did not flinch from the burden of choice, but boldly answered the summons of history.

Former Commonwealth Secretary-General Emeka Anyaoku (L) and former Ghanaian President Jerry Rawlings arrive to attend the national inter-denominational funeral rites for Odumegwu Ojukwu, at Michael Opkara Square in Enugu

As the saying goes the rest is also history.

Source:http://saharareporters.com/article/wole-soyinkas-tribute-dim-odumegwu-ojukwu

Biafra Revisited: civil war leader Ojukwu dies – By Richard Dowden

There was one astounding moment at Chinua Achebe’s Colloquium at Brown University in the US last year when three of the most influential men in the Biafran War came together on the platform – Chukwuemeka Odumegwu-Ojukwu, the Oxford educated Biafran rebel leader, Professor Achebe himself, the most articulate proponent of the Biafran cause, and Wole Soyinka who flew into Biafra to act as a peacemaker and as a result was thrown into jail by the Nigerian President, General Yakubu Gowon. Only Gowon was missing.

Just to see the three old men together was extraordinary – the slow-spoken, reflective Achebe in his beret, Soyinka with his shock of snowy hair and white beard speaking bluntly then enigmatically, and Ojukwu, a giant of a man in a huge black coat but now blind, led around by an assistant. He said very little but I wanted to ask a simple question, so when the session ended I managed to stop him for a moment and ask if he had any regrets about the war. He paused but did not turn his head. “History does not repeat itself,” he growled. “But if it did, I would do exactly the same again. Excuse me.” He moved on.

He died in London last Saturday and his death may trigger a re-assessment of that terrible war. In so many ways the Biafran conflict defined war in Africa for the rest of the century. It challenged the universal agreement among the newly independent African states to accept the colonial borders. The Ibos attempted to leave Nigeria and create their own state, (although they would have taken with them several other ethnic groups, like the Ibibios, the Annanga and the Ogojas, who were not consulted). This tribally based rebellion was to be replicated throughout the continent in following years. The war divided Africa, with Gabon, Cote d’Ivoire and Tanzania supporting the Biafran cause and other countries backing Nigeria. A divided African Union prevented it acting as a peacemaker, and from then on the AU played almost no role in ending wars in Africa.

Biafra was also about resources – oil in this case, which supercharged the conflict and ensured that outsiders like Britain took sides and supplied weapons. While not causing Africa’s subsequent wars, oil, diamonds, coltan and other valuable resources have exacerbated and prolonged conflicts. It did not however divide the world along Cold War lines. The Soviet Union also supplied weapons while the US took a neutral stance imposing its own arms embargo on both sides.

But perhaps Biafra’s greatest impact was its image. The last time the world had seen masses of starving people was at the end of the Second World War. The ‘Biafran baby’ – a starving child with huge sad eyes, stick-like limbs and bloated stomach – became a defining image of Africa for the next half century as wars broke out in almost half the continent’s states.

Aid agencies, which had had few emergencies since the end of World War II, found a new role in Biafra and there confronted all the problems they were to face elsewhere in Africa in the coming decades. A whole generation of aid workers were forged in the Biafran fire. The biggest problem for the aid agencies was that they knew some of the food and medical supplies were being taken by the combatants, thereby prolonging the war. The aid air bridge was also used by arms suppliers and one aid plane was shot down by the Nigerians. The Nigerian government tried to starve out the rebels. Chief Awolowo, then a minister, said in 1968 “all is fair in war and starvation is one of the weapons of war. I don’t see why we should feed our enemies fat in order for them to fight us harder.”

On January 12th 1970 the war ended with the collapse of Biafra and the flight of Ojukwu (although he said he would die rather than run away). General Yakubu Gowon declared that there would be no victors and no vanquished and there appears to have been no retribution once the fighting stopped. But there was no peace building or reconciliation either. Nigeria returned to peace, Ojukwu returned to Nigeria and was given an official pardon. But many Ibos feel they have been excluded from high office ever since and there has been little discussion of the war or its effects. The history of the war and its causes is not taught in schools and until Chimamanda Adichie’s novel Half of a Yellow Sun there was no written memory of what happened.

Perhaps with the death of Ojukwu that will change.

Richard Dowden is Director of the Royal African Society and author of Africa: altered states, ordinary miracles

NIGER-DELTA INDIGENES CELEBRATE ODUMEGWU-OJUKWU

The Coordinator, Ijaw Monitoring Group (IMG), Mr Joseph Evah, on Wednesday in Lagos urged the Federal Government to rename the Eagle Square, Abuja as ``Odumegwu-Ojukwu Square’’.

Evah made the plea at an event organised by Niger-Delta indigenes in honour of the late Ikemba of Nnewi, Chief Chukwuemeka Odumegwu-Ojukwu.

``The Federal Government should confirm the slogan that Abuja is, indeed, the Centre of Unity by renaming the Eagle Square, Abuja as ``Odumegwu-Ojukwu Square,’’ in the same way the former Race course in Lagos was renamed ``Tafawa Balewa Square,’’ he said.

Evah described Odumegwu-Ojukwu as a prophetic revolutionary and a man who believed that the Nigeria dream should be based on Justice.

``The prophetic revolutionary succeeded in convincing all actors in the civil war to sign off on what was known as the ``Aburi Accord,’’ the `famous’ document which was signed at Aburi, Ghana in January 1967,’’ he said.

Evah recalled that during the conference in Ghana, Ojukwu’s articulations and brilliance resonated and it was clear that he was a man that saw `tomorrow’.

According to him, the Aburi Accord would have solved most of the nation’s political and economic problems.

``The solutions Odumegwu-Ojukwu proffered for peaceful coexistence and national unity were based on the Aburi Accord and they are still germane,’’ Evah said.

Earlier, the chairman of the occasion, Mr Ben Murray-Bruce, who was represented, said Odumegwu-Ojukwu deserved all the honour being accorded him because he was a great man.

Bruce also suggested that the Federal Government should give Odumegwu-Ojukwu some appropriate recognition by renaming a national monument after him.

In his remarks, Mr Daniel Amassoma, President, Ijaw Youth Development Association, said Ojukwu was a leader who believed in equity, justice and fairness.

``Ojukwu was a leader the youth so much believed in; a leader that every follower would always want to follow, till the very end.

``As he has passed on, we will not be tired, but we shall continue to seek until we are able to get a leader like him,’’ Amassoma said.

In his tribute, the Eze Ndigbo of Lagos State, Chief Christian Chukwuemeka Nwachukwu, also supported the call to immortalise Ojukwu, saying he was a fighter for Justice.

``We have made an excellent suggestion to President Goodluck Jonathan and we expect that he will heed our advice and immortalise Ojukwu, as a way of showing love to a great Nigerian.

Odumegwu-Ojukwu (78), a former Military Governor of the defunct Eastern Region and a retired Nigerian military officer, who died in a London Hospital on Nov. 26, is to be buried in his hometown, Nnewi, Anambra State, on March 2. (NAN)

Okadigbo was to be the arrowhead, since he was the Political Adviser to the President. Tahir, then Chairman of the Board of Nigerian Telecommunications, was chosen because of his influence and political pre-eminence within northern political circles. Masi was an important Minister of Works in the Shagari administration and a brilliant Army Captain with the Biafran Army Engineers. General Chukwuemeka Odumegwu-Ojukwu gave these as his reasons for preferring that we worked with these eminent Nigerians.

The meeting with Tahir and Obiano

In part two of this narrative that appeared last week, I traced the initial involvement of Okadigbo in the project of Emeka's homecoming, and how I took him and Obiozo to Bingerville to meet and discuss with the General. Soon after we returned to Nigeria, we tracked Dr. Tahir at Ikoyi Hotel, where he was temporarily accommodated. He was very warm and polite to us and Okadigbo had tutored Vincent Obiano and I how to present the case to Tahir. As he chain-smoked, he listened us out and made promises he so dutifully fulfilled. We then moved to Victor Masi's official residence in Ikoyi. He was waiting for us. Obiano had contacted him, for they knew themselves at the University of Nigeria in the early sixties. Here, again, the reception was warm and friendly. Before we knew it, Emeka called Chief Ike Onunaku, a top management staff of the United Africa Company (UAC) (I mean the UAC under Chief Ernest Shonekan), who was a part of us and who hosted so many of our meetings in those difficult days, to say he was getting feelers on how effective the team had become. By this time, Emeka had asked Colonel Joe Achuzia to join us and to handle the security component of the project. We continued to meet regularly at Onunaku's Bourdillon Road, Ikoyi residence - Bless his soul.

Ojukwu met Shinkafi in London

One early Saturday morning, Onunaku sent his driver to bring me to Ikoyi. 'What about'? I asked the driver. He wouldn't know beyond the instruction to get to my Ikeja residence and 'get Kanayo here before two o'clock.' When I arrived, I was told that the General wanted to give me a new brief by 3pm, and since I didn't have a telephone at home, Onunaku's place at Ikoyi was the best option. At exactly three o'clock, the call came through and Emeka said he had just returned to Abidjan from London, where he had 'fruitful and rewarding discussions' with the Director-General of the Nigeria Security Organization (NSO), Alhaji Shinkafi. I was to constitute a strong media team to start working on softening the ground for his journey home. His meeting in London with Shinkafi had increased his optimism that his days in exile were, indeed, coming to an end, he said. He sounded slightly excited, and I was happy and so was Chief Onunaku.

The media campaign

Two days later, I traveled to Enugu on a Nigeria Airways flight, in the company of Vincent Obiano. We were in Enugu to ask for the support of a good friend and colleague, Obinwa Nnaji, who was then Editor of Sunday Satellite of the Satellite Newspaper Group in Enugu. We confided in him and told him precisely how the General wanted the media aspect of the project handled from the East. After getting his advice, support and firm commitment, Vincent and I came back to Lagos. The following day, I drove to Iwaya Road Yaba, Lagos to brief and request the support and sympathy of veteran journalist and editor, Gbolabo Ogunsawo, the former editor of Sunday Times. Emeka knew him by reputation and specifically advised me to reach out to him. In his days as the editor, the weekly was reputed to be the highest circulating newspaper in Africa, south of Sahara. And from exile, he was a loyal reader of Sunday Times.

We secured Gbalabo's sympathy and through him the understanding of the Unity Party of Nigeria, as well as access to as many editors in the Lagos/Ibadan media axis as possible. Obinwa Nnaji also inherited the duty of getting his editor colleagues in the South East to step up the media campaign. Before we all knew it, Ojukwu's return to Nigeria had developed into a huge national discussion and conversation. Indomitable Tai Solarin added his voice in an article that was published in both the Nigerian Tribune and the Daily Sketch.

The debate was now widening and going in the direction we had planned. And Emeka was letting us know that he was following developments closely but warned: 'You must not relent until Shagari pronounces the magic word 'Emeka, Come Home.'' Dr. Chuba Okadigbo was doing just fine in the political turf. He called me one day to say that the media tempo must not go down at all. Gbolabo, Obinwa and I were taking care of the media angle. Colonel Achuzia (now a chief in his native Asaba and its Ochiagha) was making progress with security arrangements. Everything was going good. Everybody was cooperating and the end of Emeka's days in exile was nearing its terminal stage.

Shagari's declaration

In a terse statement issued by the presidency, Shehu Shagari allowed Emeka to come home and a huge volley of joy and jubilation were unleashed. Preparations for his trip home began in earnest. Individuals and groups that were afraid to mention Emeka Ojukwu's name in public since January 1970 began to come out of their holes, like termites. I remember one fellow who refused to touch the letter from Ojukwu to him in 1972, and even warned Emeka Enejere and I never to mention that we ever saw or came to his office located in central Lagos, was busy granting elaborate press interviews soon after the amnesty announcement. He was hailing the General as 'my infinite hero,' who is on his way back home. Such is life.

At the end of it all, however, many genuine Igbo groups made contacts with us and began to donate time and buses that would convey people to Lagos and back.

The Cote d'Ivoire angle

Many Ivorians, too, voluntarily donated huge sums for the printing of thousands of T-shirts. Emma Ackah, an Ivorian presidency staff, was in-charge of that. Emeka had instructed what should be written on the shirts - simple Igbo words, 'ONYEIJE NNO.' What happened at the airport the day he arrived Nigeria is now history. The day his body arrives Nigeria will record yet another history.

It is on this note that I say, with tears in my eyes, to my General, mentor, adviser and ogam: sleep well and good night - Chukwu nabata mkpuru obi gi. Ka emesia!

source:http://www.thenigerianvoice.com/nvnews/77878/1/how-shagari-granted-ojukwu-amnesty.html

What was your childhood and growing up like?

My birth was said to be special in that my mum was barely seven months pregnant when I came prematurely with my twin sister. We were said to have been covered with all sorts of clothing, wool and other things to make us warm. My mum could not offer bosom milk because she was not too well and so we had to be bosom-fed by other women. I made it but the other child didn’t. I was named Njideka, which means “I am grateful for this child.”

My parents had seven of us, one died at thirteen and I became the second from the original third position among the children. I attended St. Monica’s in Onitsha and Archdeacon Crowder Memorial Girls School, Elelenwo, near Port Harcourt. I was born in a Christian family. My parents were very strict Christians. It’s difficult to say this, but the truth is that I was born in abundance. I had everything I wanted. True also is that it wasn’t a happy childhood. My father, for reasons best known to him, wanted very much to marry me off and yet he had five daughters, I was number two.

Coming from a wealthy home, how was school like?

It was not easy at all. Teenagers had their own ways of thinking. We had so many people. My father would not allow one to say hello to a man.

But here was I, in Elelenwo, with students from University College, Ibadan coming to teach. I will be going on, and see one and say hello, or shake hands, my father would see that and descend on me. Our house was so high that he could see you from afar. In any case, I was not ready to play hide and seek. I read a lot, stayed indoors a lot.

My father was one of the pioneers in the recording business. There was another called Joe Febro, though I have forgotten the man behind it. Those days, they used to work together.

My father, had seven living children I was first number three, but when the eldest died at thirteen, I became the second.

How did your relationship with Ojukwu start?

It was after my divorce from Dr. Brodi-Mends, a Ghanaian and the father of my first child, Iruaku. Ojukwu is somebody you see around or bump into because our parents were business people. I’d seen him the day my younger sister was going to England at the airport. She knew him before me. Later on, he told me my sister was my best ambassador. That she was always talking about me and that I was always at home.

Then, you had to fly by a small aircraft from Enugu to Kano to join the British Airways. So, we had gotten to the airport when my name was announced, I was shocked. I had the feeling that maybe something terrible had happened to my father. My hands were shaking when they were giving me the telegraph. I opened it and what was the content: “I am sorry; I mean to come to meet you at the airport. But I was sent to Kpeshi (Teshie) in Ghana. Emeka. “When I read it, I had to wonder, why is he concerned and where is “Kpeshi”. Because, I was not familiar with military locations.

After that, I went to London and continued with my life, until three years later, when I met him again at a tube station. I had gone with a friend of mine, Mrs. Obiekwe, she is late now. While we were going with the husband, somebody just said ‘they do not greet people in Igbo.’’ I turned back and lo and behold, it was Emeka, who had escorted his father to the station.

He said he was on a course and asked for my phone number and I gave him. A week later, he called. “Hello, I am very sorry I have not been able to call,” he said, I said no problem, in any case, you give your number to several people not with any expectation that they’ll call. We met on several occasions thereafter. He pursued me like I have never experienced. At a point he asked me about a Canadian friend of mine and said that I had to let go of him.

One major reason I didn’t mind him was my father. I was afraid he could have a heart attack and die if he got to know I had a white friend. By then, we were thinking of a serious relationship.

Anyway, Emeka was calling and calling and staying on the phone. I didn’t realize what he was up to until I asked him why he liked wasting time and money on phones. He asked if I really wanted the truth, then revealed that he wanted to take that my friend, who he had christened “Canada.” off me! (laughter).

One day, Emeka invited me to his house. I took a friend of mine, Efun Shobande, with me. We got to his house and he took me aside. So, you brought someone to come and spy on me? I laughed it off but that was indeed why I brought my friend with me.

By the way, I lost contact with Efun and have not seen her since. I understand she was married and was in Kaduna, she was brought up in Jos.

On the way back the next day, we talked about him and I was so confused, that when we go to Baker Street, I almost passed out.

Efun told me that she liked and preferred Emeka. In any case, she added, “he is a Nigerian.”

I thereafter, told him to get in touch with my parents if he was serious. He had known about Iruaku, my daughter by Brodi-Mends. She was two when I left home. When I got back to Nigeria, I saw a huge teddy bear with Iruaku and when I asked who gave it to her, I was told it was Emeka.

He had obviously wooed everybody in the house over. My mother and the rest were all in love with him. Our parents, fathers were well known to one another, though they are from Nnewi and we are from Nawfia, not too far from Awka.My mother and the rest were all in love with him. Our parents, fathers were well known to one another, though they are from Nnewi and we are from Nawfia, not too far from Awka.

Your marriage with Ikemba started on a high. He was a military man and all that… Did you know he was in the military when it started.?

I knew he was a soldier. But I didn’t know much about what being a soldier meant. There was a day he came home while in London with the British Army uniform, I asked him and he said he is on course and so have to put on the uniform during the duration of the course.

I only got to know more when I came back. The first party he took me took me to was Ironsi’s. I didn’t remember seeing many women there. I remember seeing Murtala Mohammed who was then Ironsi’s Aide De Camp. The men were so polished; spoke impeccable English, well mannered and unbelievably polite. I was pleasantly surprised. So we had people like this in Nigeria? I sort of liked them. The crop I saw was impressive. And Emeka was very good at taking care of a woman.

Was he randy, full of soft words, romantic?

I didn’t even know the word is romance. Not really. He is just a very kind man, very polite, not intrusive. He cared less about what happened in the kitchen, he just settled for whatever you offered him. He respected me and my opinion a lot. Later, when the children got across to him, he would ask them what my opinion was on issues. And I loved him immensely in return.

If you were this in love, why the separation?

Well, somebody summed it up: Fredrick Forsyth in his book. He knew the very beginning of the story. I agree with him that it is the war. I suppose, in a given situation, where things are very bad, there is always a casualty. I guess I was the last casualty of the war.

I do not hold Emeka responsible. I think there was pressure on him to have another wife and he was resisting. And you know there are other undercurrents that are better left in the past where they belong.

So, one day, you just decided to leave him or he asked you to leave?

No, I just left. I disappeared. I went to London. Okigbo my last son was then around two and a half years. He didn’t allow any of the children to go with me. Eventually, we communicated again and I got the children back.

Maybe the problem is that I can’t tolerate distraction in my marriage. I gave all, my soul, life and all and could not stand ridiculous stories. The unfortunate part of it all was that I kept marrying single sons. But if I had married again and had trouble, I would just have left I love my peace.

Since then, what have you been doing?

I have been doing business. When I was in London, I was ordering George, jewelleries from India, Italy and selling them to other traders. I couldn’t continue with my education, so I went into buying and selling. Some people asked me, what was Deka (West Africa) Limited (my company) into? And I answered: we sell everything except illegal things.