NDEBELE (MANALA NDEBELE AND NDZUNDZA NDEBELE) PEOPLE: SOUTH AFRICA`S ARTISTIC, COLORFUL DRESSING AND PEACEFUL PEOPLE

Ndebele (South/original Ndebele) people artistic Bantu-speaking people of Nguni extraction comprising abakwaManala (the Manala Ndebele) and abakwaNdzundza (the Ndzundza Ndebele) located in South Africa and Zimbabwe.

The people refer to themselves as "AmaNdebele," or "Ndzundza" or "Manala," denoting the two main tribal groupings. They are distinct from Mzilikazi`s led Northern Ndebele people popularly known as Matebele people of Zimbabwe and South Africa. Ndebele people are also known as the Southern Transvaal Ndebele, and are centered around Bronkhorstspruit in the Republic of South Africa.

Ndebele women from Gauteng wearing colorful traditional clothings during the National Women's day in Pretoria.

The so-called Southern and Northern (ama) Ndebele of the Republic of South Africa constitute a single ethnic group that claims its origin from the ancestral chief, Musi (or Msi). According to scholars Fourie (1921), Van Warmelo (1930), Van Vuuren (1983), De Beer (1986), Skhosana (1996) and others, the (ama)Ndebele originate from KwaZulu-Natal. Long before Shaka's wrath they parted as a bigger clan from their main Hlubi tribe around 1552 under the chieftainship of Mafana and took their route northwards. The other clan also separated from the main (ama)Hlubi tribe and went south via Basotoland. The clan that went south ultimately became part of (ama) Xhosa Nguni people who are presently found in the Eastern Cape.

Ndebele initiation of boys

The first group that parted from the main Hlubi group (i.e., (ama)Ndebele) crossed the Vaal River and entered the then Transvaal and settled themselves around eMhlangeni, known as Randfontein, which is on the western side of Johannesburg (Van Vuuren, 1983:12). From eMhlangeni, they moved to KwaMnyamana (also known as Bonn Accord) near Pretoria, and arrived there in 1610.

Young Ndebele girls in their traditional attire

At KwaMnyamana, (ama)Ndebele were under the chieftainship of Musi who, according to Fourie in Van

Warmelo (1930:10), had five sons, namely Manala, Nzunza, Mhwaduba, Dlomu and Mthombeni.

However, according to Van Warmelo (1930:10), Sibasa was the sixth son of Musi while Massie in Van

Warmelo (ibid. 10) claims that the sixth son of Musi was M'pafuli (or Mphafudi).

Ndebele woman

The South Ndebele people found in the former Transvaal today consists mainly of two tribes, namely, abakwaManala (the Manala Ndebele) and abakwaNdzundza (the Ndzundza Ndebele). The population census of 1980 indicated that the Ndebele people in South Africa numbered some 392 420. This number was composed as follows: 27 100 in urban areas and 87 940 in former KwaNdebele and 33 480 in the other parts of South Africa. (Population Census, 1980,3-4).

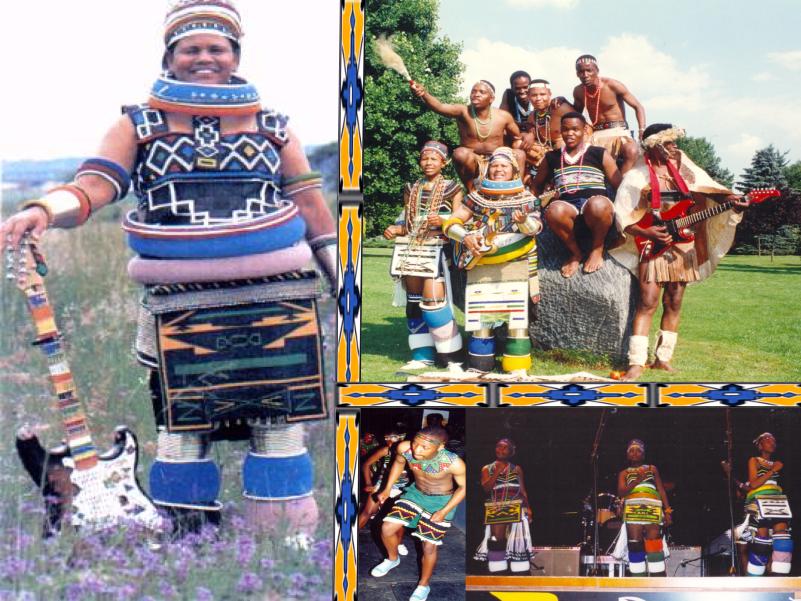

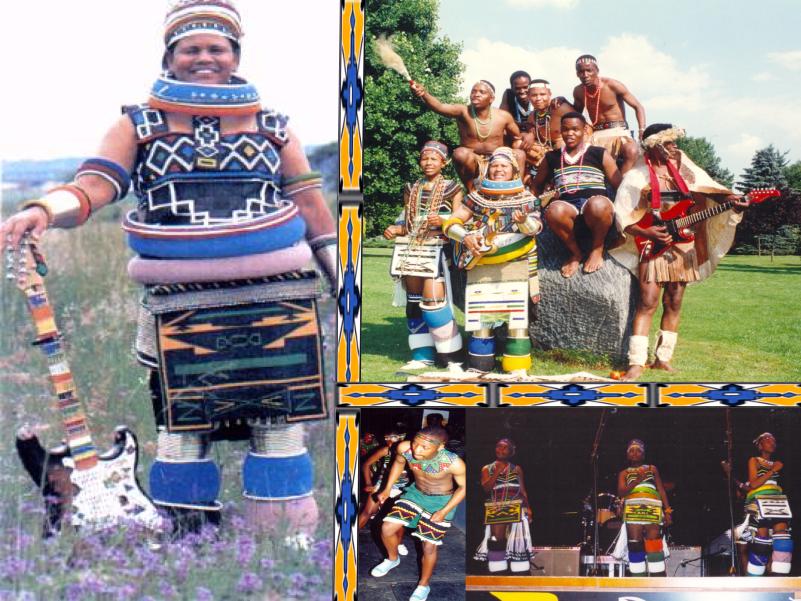

The Ndebele are noted for their Colorful dress and their artistic creativity, which includes sculpted figurines, pottery, beadwork, woven mate, and their celebrated wall painting. An outstanding example is the breaded nguba, a "marriage blanket" which the bride to be, inspired by her ancestors, makes under the supervision and instruction of the older women in her ethnic group. Traditionally the women work the land and are the principal decorators and artists, while the men fashion metal ornaments such as the heavy bracelets, anklets and neck rings that are worn by women.

Traditional Ndebele attire: beaded leg bracelets

Ndebele homes are, perhaps, the most eye-catching local style. Women, using bright primary colors, traditionally paint walls of the rectangular structures. No stencils are used for the geometric motifs

Ndebele women in North West, South Africa

Location

The majority of Ndebele live in the former Bantustans or "homelands" of KwaNdebele and Lebowa, between 24°53′ to 25°43′ S and 28°22′ to 29°50′ E, approximately 60 to 130 kilometers northeast of Pretoria, South Africa. The Southern Transvaal Ndebele people now lives specisely around Gauteng and Mpumalanga provinces of RSA whilst the Northern Transvaal Ndebele (now Limpopo Province) are also around the towns of Mokopane (Potgietersrus) and Polokwane (Pietersburg).

The total area amounts to 350,000 hectares, including the Moutse and Nebo areas, which were previously part of the former Lebowa homeland. Temperatures range from a maximum of 36° C in the northern parts to a minimum of -5° C in the south; rainfall averages 50 centimeters per annum in the north and 80 centimeters per annum in the south. Almost two-thirds of the entire former KwaNdebele lies within a vegetational zone known as Mixed Bushveld (Savanna type), in the north. The southern parts fall within a zone known as Bankenveld (False Grassland type)

Language

IsiNdebele is the beautiful African or Bantu language spoken by the Ndebele people of South Africa who are also sometimes known as the amaNdebele. IsiNdebele forms part of the “Southern Bantu” group of African languages, which in turn forms part of the larger Niger-Congo language family. IsiNdebele is one of the officially languages of South Africa.

The Central subgroup is further subdivided into geographical regions, each designated by a letter. The S-Group covers much of southern Africa and includes the two major dialect continua of South Africa: the Nguni and the Sotho-Tswana language groups. Languages within these two groups tend to be mutually intelligible and the groups make up 47% and 25% of the South African population respectively. IsiNdebele forms part of the Nguni language group and is therefore closely related to the other major languages in this group, isiZulu, isiXhosa and siSwati. Linguists commonly drop the language prefix when referring to these languages. Hence isiNdebele is commonly referred to as “Ndebele.” This practice is, however, contested and in South Africa the official use of the prefixes has increased during the post-apartheid period. In South Africa isiNdebele is also commonly known as Southern Ndebele, to distinguish it from the Zimbabwean variety or Northern Ndebele (also known as Sindebele). IsiNdebele is also occasionally referred to as isiKhethu.

The Southern Ndebele speakers are found in the Limpopo Province which was formerly known as the Northern Transvaal (also known as Nrebele). They can be found in and around Mokopane and Polokwane and are few in number. Because no one ever compiled a proper orthography for the language, it has never been taught in schools and is slowly dying out. Most of the younger Southern Ndebele now speak Northern Sotho since the language is considered by many to be more versatile and useful.The Northern Ndebele speakers are found mainly in Mpumalanga and Gauteng.

All isiNdebele speakers trace their roots to Nguni migrations out of the region that is now known as KwaZulu-Natal. The earliest of these settled in the Pretoria area in the 1600's. After the death of their king, Musi, the kingdom was split between his two sons, Manala and Ndzundza. The two main South African traditions, Manala in the Pretoria area and the Ndzundza further east, derive from this split. During the 1820's Mzilikazi broke away from Shaka’s Zulu Kingdom and fled northwards, settling ultimately in the region that is today Bulawayo in Zimbabwe. That is the origin of the Ndebele of Zimbabwe.

In 1994 isiNdebele became one of nine indigenous languages to obtain official recognition in South Africa’s first post-apartheid Constitution. The 2001 South African census estimates the number of isiNdebele speakers to be 711824. At 2% of the population, isiNdebele speakers make up the smallest official language group in South Africa.

IsiNdebele is an agglutinating language, in which suffixes and prefixes are used to alter meaning in sentence construction. Like the other indigenous South African languages, isiNdebele is also a tonal language, in which the sentence structure tends to be governed by the noun. Examples of phrases in the language include: lotjhani (hello); Unjani? (How are you?); Ngikhona (I am fine).

As a written medium isiNdebele is one of the youngest indigenous languages in South Africa, as formal codification began in the late twentieth century. The language has a very small literature, most of which dates from 1984. The most significant literary work is the Bible, which was translated in 1986. Ironically, most of this language development took place during the Apartheid years.

Hail to the host: Bongani's father wears the skin of a jackal -- known as iporiyane -- signifying that he is the host of the ceremony. (Oupa Nkosi, M&G)

During the apartheid period, the ruling National Party’s policy of Grand Apartheid was built on a vision of ethno-linguistically discrete territories for South Africa’s indigenous population. Beginning after 1960, the widely condemned “Bantustan” policies of Prime Minister H.F. Verwoerd resulted in the creation of ten self-governing territories in predominantly rural areas of South Africa.

Thus the independent territory of “KwaNdebele” was established in 1984, in the Transvaal (today the Northern Province), to serve as the designated homeland of isiNdebele speakers. Under apartheid separate language boards were also created for each of the nine standardized indigenous languages. These boards effectively appropriated the work of language development that had previously been done by missionaries. In 1976 the South Ndebele Language Board was established. The board sought to formulate spelling rules, compile a vocabulary list for schools, and promote the production of written materials. The board also had an oversight function – preventing the publication of politically challenging material. From 1984 the language was taught for the first time as a subject in primary and secondary schools. A number of schools also began to use it as a teaching medium. The KwaNdebele territorial authority was disbanded in 1990 and now forms part of the Northern Province administration.

Boys to men: Bongani Sindane bids farewell to his family. (Oupa Nkosi, M&G)

Following the democratic transition 1994 responsibility for language policy and development now rests with the Department of Arts, Culture, Science and Technology. A new body – the Pan South African Language Board (PanSALB) – was also created and charged with responsibility for language planning. PanSALB has sought to facilitate the further development of the language. Under PanSALB, the isiNdebele Lexicography Unit is responsible for developing new terminology for the language. The functional development of the language is proving rather difficult. Education poses particular problems. Until recently isiNdebele speakers tended to learn Zulu at school. Although the language is now taught as a subject at both primary and secondary level, it is only used as a medium of instruction from grade 1 to grade 3.

As a very small language, the development of isiNdebele faces particular economic difficulties. The heartlands of the language are situated in predominantly rural regions. High unemployment means that many young Ndebele speakers are compelled to move to towns and cities in order to find work. Here they invariably come into contact with speakers of other languages – including closely related languages such as Zulu, which they understand and often adapt to. They received their own radio station, Radio Ndebele which was later renamed to Ikhwekhwezi (Star) in post-apartheid years. It might be said that the radio station has largely contributed to the continued use of the Northern Ndebele language and much of the vocabulary remains the same with the exception of a few Northern Sotho and Afrikaans words which have become commonplace. IsiNdebele is used on radio and shares a television channel with other Nguni languages. There are no isiNdebele newspapers.

Proud day: Mothers of the amasokana look on as their sons perform. (Oupa Nkosi, M&G)

History

The origin of the name "Ndebele" is full of speculations and there are many school thoughts. The necessity of trying to trace the origins of the term "Ndebele" has become apparent. Some school of thought posit that Mzilikazi, who originated from Zululand and led the breakaway factions from the Zulu people called himself Ndebele. It is however not very clear as to when he actually started calling himself Ndebele because historically there are no facts indicating that he ever used the name whilst still in Zululand. This is aggravated by the fact that, the people who now live across the Limpopo in Zimbabwe call themselves Ndebele as well.

Ndebele people. Circa 1940. Courtsey http://www.ezakwantu.com/

D W Kruger in his 1983 seminal work "The Ndzunclza-Ndebele and the Mapoch caves, Pretoria" tried to solve this confusion saying "The Transvaal Ndebele, who comprise the Northern and Southern Ndebele, should not be confused with the Ndebele or Matebele of Mzilikazi (Silkaats). The latter were "recent"

immigrants (c 1825) into the Transvaal originating from the Khumalo in NataL

According to historical data, the Ndebele must have been of the earliest immigrants into the Transvaal, and came here most probably before 1500. This makes the Transvaal Ndebele in all likelihood the earliest Nguni immigrants into the TransvaaL It is however, not clear at what stage and where the branching off from the main Nguni group took place".(Kruger, 1983,33).

It is clear from Kruger`s account that, firstly. the Ndebele people found in the Transvaal today are not the same group as those found in Zimbabwe. The group found in the Transvaal today is estimated to have been there at least three centuries before the arrival of Mzilikazi. (sic!) Secondly, although the name "Ndebele" is shared by both the groups, ill actual fact one of the groups must have "inherited" the name.

P S Mthimunye a history researcher wrote in an unpublished manuscript that the name "Ndebele" was another name by which the first chief of the Ndebele people was known. According to the same writer, chief Ndebele and chief Mafana were one and the same person. The issue here is that the name Ndebele was derived from an early Ndebele chief and can by no means be connected to the Zulu or Zululand. Just like in most African nations, the name of the first king normally becomes the name whereby the nation as a whole becomes known. We can think here of the Swati people of king Mswati; the Shangane people of Soshangane; the Bashweshwe people of king Moshoeshoe etc.

The other school of thought of how Ndebele people got their name was led by historian Rasmussen when he writes: "the name 'Ndebele' is a good example of the almost universal tendency of people receiving their names from outsider."(Rasmussen, 1978, 161). He further points out that the name "Ndebele" is a Nguni

version of the seSotho name "Matebele". He says that this name was used by the Sotho people to refer to any member of the Nguni group who came from the "East". It has been used on several other Nguni people other than Mzilikazi. The Sotho people used this name on all Nguni speaking people, most probably, because they found "little difference", if any at all, in the languages spoken by the latter. He concludes: 'Eventually the name 'Matebele', or 'Ndebele' in its Anglo/Nguni form, came to apply only to Mzilikazi's people and to the 'Transvaal Ndebele'. These latter were the descendants of much earlier Nguni immigrants onto the highveld. (Rasmussen, 1978, 162).

Ndebele Woman at Wall (South Africa), 1936-1949. By Constance Stuart Larrabee

The oral version among the Africans explained why Ndebele became Matebele by stating that the name Matebele comes from Sotho words "mathebe telele", meaning "carriers of long shields". It is only Shaka's warriors who are known to have carried long shields. This idea of long shields is said to be Shaka's own, and no other king before Shaka is known to have employed this type of war armoury. When the Sotho people saw these long shields for the first time, to them it was just a queer sight. Because of the fact that it is not easy to pronounce "mathebe telele" in a fast speech, one ends up saying "matebele'.

The last school of thought believes that the Ndebele people originated from Zululand but left Zululand quiet early. This view estimates that the breakaway time could be during the sixteenth century, certainly many, many years before the Shaka period. An interesting view is the one documented by Skhosana. He writes: "AmaNdebele adabuka kwazulu eminyakeni yabo 1557, abamhlophe bangakalibeki inyawo labo kileli leSewula Afrika. Aphuma kwazulu asitjhabana esincani ekungaveli kuhle bona sasibuswa ngiyiphi ikosi.

(Skhosana, 1996, 5) which translates as "The Ndebele people originated from Kwazulu around 1557, this was before the arrival of white people in South Africa. They were a small group when they left kwazulu and it is not very clear who their king was at this time." (Skhosana, 1996,5). It presupposes that the Ndebele people originated from Zululand around the year 1557. They were a small nation and it is not very clear who their king was at the time.

On Mzilikazi who is a founder and leader of Northern Ndebele (Matebele) people, it is said that Mzilikazi on his way to the North, fleeing from Shaka, must have requested for "political asylum" from among the original Ndebele (Southern Ndebele) people. There is also a view that, Mzilikazi, a former Shaka warrior, impressed the Ndebele people with his impi techniques he learned from Shaka, so much that he gained himself a good name of being a hero.

According to Skhosana (Skhosana, 1996, 8) the encounter between the Ndebele people and Mzilikazi was not that harmonious. A fierce war was waged and Mzilikazi was victorious. Mzilikazi left a trail of destruction wherein he murdered two Ndebele chiefs before proceeding to Zimbabwe. Skhosana writes "Ngesikhathi kwaMaza kubusa ikosi uMagodongo, kwafika uMztlikazi abaleke kwaZulu ngestmanga sezipi zakaShaka.

UMzilikazi wafika wasahlela uMagodongo nesitjhaba sakhe. Uthe bona abulale uMagodongo uMzilikazi, wathumba ifuyo nabafazi wanyuka nenarha watjhinga eTlhagwini, waze wayokunzinza eRhodesia

esele yaziwa ngeZimbabwe namhlanje. UMzilikazi wathi nakasahlela uMagodongo kwabe sele adlule ngakuManala, abulele uStbindi. (Skhosana, 1996, 8). This is translated as "During the reign of king Magodongo at kwaMaza, there arrived Mzilikazi who was fleeing from Shaka wars in KwaZulu. Mzilikazi killed Magodongo and thereafter took as captives stock and wives and went Northwards, and ultimately

settled in Rhodesia known today as Zimbabwe. When Mzilikazi attacked Magodongo, he had already passed via Manala and killed Sibindi. (Skhosana, 1996, 8).

In researching all the various historical account its now an established fact that the history of the Ndebele people can be traced back to Mafana, their first identifiable chief. Mafana’s successor, Mhlanga, had a son named Musi who, in the early 1600’s, decided to move away from his cousins (later to become the mighty Zulu nation) and to settle in the hills of Gauteng near where the capital, Pretoria is situated.

Historically, KwaMnyamana is the most important settlement area of the (ama) Ndebele of the

Republic of South Africa, because it is the place where the (ama)Ndebele split into two main groups

and numerous smaller sub-groups. When Musi died in 1630, the succession struggle ensued between

two of his sons, namely Manala and Nzunza, and the tribe split into the Southern and Northern (ama)Ndebele, respectively, as well as other smaller tribes. The Southern (ama)Ndebele comprised

the followers of Manala and Nzunza while the Northern (ama)Ndebele consists the followers of Mthombeni. Together with his brother, Nzunza, Mthombeni left KwaMnyamana until at KwaSimkhulu, north of Belfast in the present Mpumalanga Province. It is at KwaSimkhulu where Mthombeni, the founder of the Northern (ama)Ndebele, parted ways with Nzunza and strategically moved northwards along the Olifant until he reached his present place of abode, around Zebediela. On his way northwards, Mthombeni inherited a new name known as Gegana (or Kekana) and his followers were referred to as the ‘people of Gegana (or Kekana)’ instead of remaining the‘people of Mthombeni’.

In 1883, during the reign of the Ndebele chief Mabhogo (whom the Boers refer to as Mapoch), war broke out between the Ndzundza and the Voortrekker settlers (Boer) of Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek (South African Republic) over land and other resources. The Boer leader Piet Joubert led a campaign against the Ndebele leader and his people. For eight months, the Ndebele held out against the onslaught by hiding in subterranean tunnels in their mountain stronghold at Mapoch’s Caves near the town of Roossenekal.

From time to time, Mabhogo’s brave warriors crept past the enemy lines undetected to fetch water and food. However, after two women of the tribe had been ambushed in the nearby woods and tortured, one revealed the Mabhogo’s whereabouts. After Mabhogo’s defeat, the cohesive tribal structure was broken up and the tribal lands confiscated. Despite the disintegration of the tribe, the Ndebele retained their cultural unity.

Ndebele wars continued under Chief Nyabela. Ndzundza lost their independence, their land was expropriated, the leaders were imprisoned (Chief Nyabela to life imprisonment), and all the Ndebele were scattered as indentured laborers for a five-year (1883-1888) period among White farmers. The Manala chiefdom was not involved in the war and had previously (1873) settled on land provided by the Berlin Mission, some 30 kilometers north of Pretoria, at a place the Manala named KoMjekejeke (Wallmannsthal).

Chief Nyabela Mahlangu was released after the Anglo-Boer War (1899-1902) in 1903 and died soon afterward. His successor tried fruitlessly in 1916 and 1918 to regain their tribal land. Instead, the royal house and a growing number of followers privately bought land in 1922, around which the Ndzundza-Ndebele reassembled. Within the framework of the bantustan or homeland system in South Africa, the Ndebele (both Manala and Ndzundza) were only allowed to settle in a homeland called KwaNdebele in 1979. This specific land, climate, and soil was entirely alien to them.

Ndebele women in South Africa in their traditional costume

Ndebele Boer Wars

AN AFRICAN MASADA Nyabela, Mampuru and the Defence of Mapochstad (by by David Saks)

When the 1880s commenced, with the dramatic defeats of the powerful Zulu and Pedi kingdoms at the end of the previous decade still fresh in the memory, it was clear that the days of African independence in South Africa were numbered. Only a handful of black tribes across the Vaal River had yet to succumb to the military and technological superiority of the all-conquering Europeans. In the course of the next two decades, these last outposts of black autonomy would fall, one by one, before the relentless expansion of the Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek (ZAR).

The military expeditions through which all this came about were, in general, dreary affairs, with few noteworthy incidents to make them memorable. The Transvaal Boers, intent on reducing their opponents to submission as quickly and cheaply as possible, went about their work with business-like caution, opting wherever possible for methods of systematic attrition over open clashes of arms. For all that, there was a certain grim drama in these little-known campaigns, a sense of tragic inevitability in the skirmishing and sniping before the brooding mountain fortresses where South Africa's last remaining free blacks made their last doomed stand.

The year 1882 began with the Transvaal Boers enjoying their second year of independence, having disposed of their imperial adversaries with remarkable ease in a short, sharp war of independence concluded the previous year. The year ended with the commandos once again in the field, this time against Nyabela's Ndzundza clan. An Ndebele people, the Ndzundza occupied the wild, hilly terrain bordering the ZAR's Middelburg district.

Nyabela's royal headquarters, KoNomtjarhelo, was built by his father Mabhogo (whom the Boers referred to as Mapoch) in the 1830s. Mabhogo commissioned various renowned land surveyors, hunters and military experts, who were subjects of the Swazi King, Mangwane, to layout his capital. The area they selected consisted of ravines and hills, strewn with boulders and honey-combed with intricate caves. KoNomtjarhelo was laid out with large cattle pens, terraced agricultural fields and irrigation ducts fed by water springs. An interlocking system of fortresses, subterranean tunnels, rock barriers and underground bunkers was constructed for defensive purposes. The Ndzundza kingdom comprised 84 km2 and had a population of 15 000 when Nyabela became regent chief in 1875.

During the first four decades of white settlement, the Ndzundza had managed to maintain a fragile autonomy. At first, they were in a client relationship with the new arrivals, paying taxes for the lands they occupied and accepting the writ of the local commandant. In the 1860s, this overlordship was challenged by Chief Mabhogo, who managed to withstand a prolonged war of attrition and eventually compelled the ZAR to recognise his jurisdiction over the lands that his people occupied.

Signs of manhood: Beads (umncamu) are wrapped around the amasokana ahead of the rite. (Oupa Nkosi, AFP)

The Boer-Ndzundza truce was maintained during the 1870s, and the two even came together at one stage to fight against Sekhukhune's Pedi further east. It was only after the Transvaal regained its independence in 1881 that the relationship began to deteriorate rapidly. The ZAR was annoyed with Nyabela for asserting his independence (by, for example, declining to pay taxes, refusing to hold a census when instructed to do so and preventing a boundary commission from beaconing off his lands). What eventually became the casus belli was Nyabela's decision to harbour the renegade Pedi chief, Mampuru.

For years prior to this, Mampuru had been engaged in a power struggle with his half-brother, Sekhukhune. In mid-1882, some of his followers attacked the old chiefs kraal and murdered him. On two previous occasions, the ZAR authorities had attempted to arrest Mampuru for fomenting disorder, and this latest outrage was the last straw. Mampuru and his supporters sought refuge with Makwani, one of Nyabela's subordinate chiefs. When ordered to extradite the fugitive, Nyabela made the fateful decision not to do so. Whatever his reasons, it gave credence to rumours that he and Mampuru were jointly plotting to coordinate a general uprising of black communities in the Transvaal against the Boer republic. War was inevitable.

On 12 October, the Volksraad authorised General Piet Joubert to raise a commando. At first, only Mampuru was the target of the expedition, but, at the end of the month, Joubert was also instructed to bring to heel any blacks who had harboured or assisted him. Joubert had little enthusiasm for his latest brief, but this would not prevent him from pursuing it to its conclusion with relentless thoroughness.

Raising enough able-bodied burghers for the expedition was not an altogether easy task. Few relished having to leave their farms for months on end to take part in a dull and prolonged campaign against rebellious blacks, even under a leader as respected and popular as Joubert. Nevertheless, an expeditionary force was duly raised. The white citizens of the ZAR had few civic obligations, but serving on commando was one of them, and most of those called out reported for duty.

Places, everyone: Abonobhova [women] and men are forbidden from sitting together at the initiation ceremony. (Oupa Nkosi, M&G)

By the end of October, the vanguard of Joubert's commando, which was about 2 000-strong, began arriving in Mampuru's territory. An ultimatum was sent to Nyabela, giving him one last chance to surrender Mampuru and to undertake to cooperate with the Republican authorities in future or war would ensue. Joubert was anxious that he comply as a military campaign was not likely to be an easy one. For one thing, illicit trading in guns had provided both Nyabela and Mampuru with extensive firearms, albeit of a relatively poor quality. For another, the latter would be defending terrain that was ideal for defence. Any hopes he might have had for compliance were soon disappointed. Nyabela famously answered that he had swallowed Mampuru, and if the Boers wanted him they would have to kill him and take him out of his belly.

The Ndzundza capital of KoNomtjharelo was a formidable fortress. It was here that the Ndzundza had rallied and entrenched themselves to withstand Mzilikazi's reign of terror half a century previously. The stronghold was situated between precipitous cliffs and sheer rock faces on the eastern extremity of a range of heavily forested, boulder-strewn hills. A complex network of caves, grottos and tunnels pockmarked these heights, providing both places of refuge and space for storage to help withstand a long siege. The caves were a remarkable phenomenon, some being so extensive as to enable fighters to disappear into one entrance and reappear from a different one more than a kilometre away. Moreover, to capture the main stronghold, the attacking force would first have to overcome a series of well-fortified hills, most notably KwaPondo and KwaMrhali (called 'Vlugkraal' and 'Boskop' respectively by the Boers; KoNomtjharelo was simply 'Spitskop') which guarded its approaches to the west.

Joubert would ultimately eschew direct attacks against these strong points. The Boers were past masters when it came to storming hills (as they had demonstrated at Majuba and Schuinshoogte the previous year) but in this particular war they could not be relied upon to take too many risks. Already half-hearted about the coming fight, they were liable to desert or simply refuse to cooperate. Instead, therefore, Joubert's chosen strategy was to wear the chiefs down, confining them and their people to their mountain fortresses and allowing starvation to do the rest. This would at least minimise losses among the Boers. On the other hand, it would inevitably prolong the war. It was already known that the Ndzundza were stockpiling their grain in anticipation of a long siege.

Opening shots, November/December 1882

On 5 November, a last-ditch attempt to conclude the dispute peacefully came to nothing and, two days later, the first clash of the war took place. Without warning, a Ndzundza raiding party swooped down from the surrounding heights and began driving the commando's oxen, nearly a thousand head, towards a cave in the mountainside. The Boers were not to be caught napping on this occasion. About 150 of them galloped after the raiders, running them to ground before they reached their destination and reclaiming their cattle. About twenty Ndzundza were killed in the skirmish; the Boers suffered just one, minor, casualty.

Ndebele Men with Bicycles (South Africa), 1936-1949. By Constance Stuart Larrabee

The main body of Joubert's commando was concentrated against Nyabela while two smaller divisions were detailed to attack Mampuru. A series of simple stone or earthwork forts were built to seal off the various entrances and exits to the chiefs' territory, hemming them in. This both limited the enemy's access to fresh supplies and protected the white farmers in the vicinity. The forts themselves were tiny, triangularshaped affairs, crudely thrown together in haste. They were nevertheless accorded grand-sounding names, such as 'Fort Potchefstroom' and 'Fort Nuwejaar'. Screened by such defences, regular patrols began scouring the area, seizing what cattle they could while gradually closing in on the capital, but not without loss. On 14 November, five men were ambushed and killed.

Within two weeks of the commencement of hostilities, the KwaPondo bastion was already being menaced. Three cannon as well as a considerable amount of dynamite had since arrived from Pretoria to help reduce the defences. On 17 November, a fort was erected no more than two thousand paces away. While a second fort was being built near the first, the Ndzundza attempted to drive back the besieging force, but were themselves beaten off after two and a half hours offierce fighting with the loss of some forty men. Only one Boer was killed. The Boers brought two of their guns into the firing line during the engagement. Soon after this repulse, Nyabela sent out emissaries to discuss peace terms, but Joubert was only prepared to deal with the chief in person and sent them back. Nyabela declined to present himself, no doubt suspecting that it was a ploy to capture him.

VIPs: The mothers of the amasokana are seen as the most important the people at the ceremony. (Oupa Nkosi, M&G)

KwaPondo, a semi-circular plateau surrounded by cliffs and strewn with boulders, was subjected to a heavy bombardment on 21 November, but to little effect. The defenders merely jeered at and taunted the burghers from the safety of their breastworks. Joubert's dynamiting operations were also unsuccessful, since the warriors had taken refuge in caves that were in most cases too deep for the blasts to have much effect. Laying the charges was also a dangerous business. On 25 November, the popular Commandant Senekal and another man were lost to sniper fire in the course of those operations.

Ndebele House painting

The commando was substantially reinforced in the last week of November, many of the new arrivals being drawn from friendly black tribes in the northern and eastern parts ofthe Republic. In early December, part of the force was deployed against Mampuru, who was still in Makwane's territory. Accompanying the Boers were a large number of Pedi, who had been loyal to the late Sekhukhune and were eager to avenge his murder. On 7 December, this combined force launched a determined assault, only to retire in some confusion in the face of an unexpected counter-attack by over 600 of the Ndzundza. This, the first Boer defeat of the war, was avenged two days later in an early morning raid, during which dozens of Ndzundza were driven into a cave and all but six of them were shot or asphyxiated in the course of being smoked out.

Throughout these dreary weeks of petty skirmishing, raiding and counter-raiding, Joubert continued to draw his cordon of forts tighter. By mid-December, most of the Ndzundza subordinate chiefs had been subdued, and from then on, the attention was focused mainly on Nyabela's capital and on Mampuru. There was somewhat of a lull in the fighting until the arrival of J A Erasmus and 1 500 black levies on 30 December prompted another offensive. Two days into the new year, the commandos attacked KwaMrhali (Boskop) and eventually took it after a fierce firefight. This was one of the few set-piece battles of the war, one more hardfought than the relatively low casualty toll would suggest.

The Boers suffered more casualties nine days later when lightning struck 'Fort Nuwejaar' (Fort New Year), killing one and injuring seventeen of its defenders. Similarly, the worst defeat Nyabela and Mampuru suffered was inflicted not by the burgher force but by its black allies. On 20 January 1883, about 300 of their followers raided the kraals of two loyal tribes. They were promptly set upon by the followers of four other pro-Boer chiefs, hotly pursued and eventually almost wiped out after being trapped on the banks of the rain-swollen Steelpoort River.

Closing in, February/March 1883

On 5 February, Joubert mustered his forces for a determined assault on KwaPondo/Boskop, which had withstood the besiegers for three months. The battle began just before daybreak and raged all morning. The burghers and their black auxiliaries, in the teeth of a stubborn resistance, were forced to clear the stronghold ledge by ledge and cave by cave. Three Boers were killed and a number of others seriously wounded - no tally was made of their black casualties - before the fortress fell. The hill's fortifications were dynamited that same day to prevent the Ndzundza from reoccupying the position.

Now only KoNomtjharelo lay between the commando and Nyabela's capital. Joubert and his war council ruled out storming the position and decided instead to use dynamite against it. This would entail digging a trench up to the base of the mountain, tunnelling deeply under it and laying sufficient charge to bring it all crashing down. It was indeed a bizarre and tortuous strategy, certainly amongst the most curious ever to have been devised in modern warfare.

On 28 February, Commandant Stephanus Roos became the latest Boer casualty when he was shot dead while dynamiting a cave. It was Roos who had led the decisive Boer charge over the crest at Majuba and he died the day after the second anniversary of that famous victory. The nearby town of Roossenekal, established soon after the war, was named after him and Commandant Senekal. Its official name today is Erholweni.

Digging commenced on 2 March. Unusually heavy rains that season had softened the ground, and after only a week the trench had been brought to within 400 metres of its objective. The diggers were harassed constantly by snipers, losing one killed and several wounded during this period. The real threat to the Ndzundza by then was imminent starvation. Four months of relentless attrition had seen their crops destroyed and most of their livestock captured, and their once plentiful food stocks had dwindled steadily. By early April, all petty chiefs had submitted to the invaders. Nyabela was promised that his own life would be spared and his people allowed to remain on their lands if he did likewise. He chose to fight on instead, perhaps still hoping, even at that late stage, to emulate his father's achievement of withstanding a Boer siege some fifteen years previously.

Final Stages, April/June 1883

Fighting petered out in the closing months of the war. Joubert was content to maintain his stranglehold until the inevitable surrender, receiving constant reports that the besieged Ndzundza were close to starvation. Most of the Boers merely lounged around in their forts, kicking their heels and waiting to be relieved. Some worked on the trench, which at least provided something to do. The Ndzundza harried the diggers as much as possible. In the middle of April, they staged a successful night attack, doing considerable damage and delaying operations by at least two weeks

. In the meantime, one member of the commando, evidently a Scotsman by the name of Donald MacDonald, had defected to Nyabela. He had done so, it was believed, because of rumours that the Ndzundza had offered him copious supplies of diamonds (which may have been illegally acquired while working on the Kimberley diamond fields), in exchange for his services. Regardless of whether or not he ever received any diamonds, MacDonald proved to be of some use to his new comrades-in-arms. Amongst other things, he taught them how to catapult large boulders down onto those working below. This tactic was one of the reasons that the Boers introduced a mobile iron fort to assist them with the digging. About two metres long, with two wheels inside and eight loopholes for firing, clumsy and unwieldy, it at least ensured that work on the trench could continue in relative safety.

The war thus degenerated into a tortuous throwback to a medieval-era siege, but there was not even the satisfaction of a big bang at the end of it. Shielded by the iron fort, the diggers managed to reach the base of the hill without further mishap. They commenced tunnelling underneath it, but had not progressed very far when they were held up by a bed of rock. Operations were suspended, permanently, as it turned out.

Even then, the Ndzundza continued to fight back. Early in June, they launched a daring raid on the Boer kraals and netted themselves some 200 oxen, enabling them to hold out a little longer. At the end of the month, they also proved equal to the first and only attempt to take the stronghold by storm. About seventy of the bolder Boers, frustrated by the tedium of the siege, volunteered to rush Spitzkop and get it all over with. They had climbed to within fifteen metres of the crest when the Ndzundza counter-attacked, hurling down a continuous hail of stones and pitching the attackers headlong down the way they had come.

On 8 July, Nyabela belatedly decided to sacrifice Mampuru in the slender hope that this would end the siege. The Pedi fugitive was seized, trussed up and delivered to Joubert, but the offering came too late. The prolonged campaign had cost the ZAR a small fortune (the Volksraad later estimated the war costs to be £40 766) in addition to several dozen burgher lives lost, and Joubert was now bent on forcing an unconditional surrender. This came two days later. Nyabela gave himself up, along with about 8 000 of his people who had stayed by him to the end. As reparations, the entire amaNdebele country was usurped.

The post-war settlement imposed by the ZAR was harsh. The amaNdebele social, economic and political structures were abolished and a proclamation on 31 August 1883 divided 36 000 hectares of land among the white burghers who had fought in the campaign against Nyabela, each man receiving seven hectares. Followers of the defeated chiefs were scattered around the republic and indentured to white farmers as virtual slave labourers for renewable five-year periods. In 1895, this whole country, now called Mapoch's Gronden, was incorporated as the fourth ward of the Middelburg District. From 1979 to 1995, it comprised part of KwaNdebele, one of the 'independent homelands' established during the Apartheid era.

Ndebele house

Nyabela and Mampuru were treated as common criminals. They were tried in Pretoria and sentenced to death. Mampuru was hanged, a not undeserved fate, given his part in the murder of Sekhukhune. Fortunately, Nyabela was reprieved after the British government lodged an appeal for clemency on his behalf. Sentenced to life imprisonment, he spent fifteen years in captivity before being released. He died on 19 December 1902 at Wamlalaganye, Hartebeestfontein, near Pretoria.

The 'Mapoch War' had not been of much credit to the ZAR, neither in the manner in which it had been conducted, nor in its aftermath. Even so, it had achieved its primary aim. Another 'troublesome' pocket of African sovereignty had been extinguished and, as a result, European hegemony in the eastern Transvaal was confirmed beyond doubt.

Ndebele boys

Ndebele boys

The settlement area of KoNomtjharelo, located about ten kilometres east of Roossenekal on the road to Lydenburg, has long been held in deep reverence and has a deep emotional significance for the amaNdebele, and especially for the Ndzundza. In 1970, a statue of Nyabela was erected at the foot the hill in the presence of his descendant, Chief David Mabhogo, as well as many descendants of those who had fought there.

Ndebele wall painting

* * *

Every year on the anniversary of Nyabela's death on 19 December, the amaNdebele gather at KoNomtjharelo ('Mapoch's Caves') to venerate their ancestors and to commemorate the death of Nyabela, the last king to rule over that area, and all other traditional leaders and freedom fighters. At the 2003 Erholweni ceremony, Mpumalanga Premier, Ndaweni Mahlangu, paid tribute to Nyabela and his gallant warriors who fought so determinedly and endured so much to defend their freedom:

'It is fitting that another small step in reclaiming our history is taken not far from where our forefathers fought pitched battles in defence of encroaching colonialism and land theft. Indeed it was here that those who came before us said "no!" to colonialism. Despite being outgunned, they laid down their lives so you and I could be free. They laid down their lives in defence of their dignity, their land and their freedom. Today we meet again in these caves as proud descendants of those valiant fighters - in a different setting, in a different era, to plan for peace and not war; to promote unity and not division; to forge a common nationhood and not exclusive privilege.'

Economy

Subsistence and Commercial Activities. The precolonial Ndebele were a cattle-centred society, but they also kept goats. The most important crops, even today, are maize, sorghum, pumpkins, and at least three types of domesticated green vegetables ( umroho ). Since farm-laborer days, crops such as beans and potatoes have been grown and the tractor has substituted for the cattle-drawn plow, although the latter is still commonly used. Pumpkins and other vegetables are planted around the house and tilled with hoes. Cattle (now in limited numbers), goats, pigs, and chickens (the most prevalent) are still common.

Ndebele maidens

Industrial Arts.

Present crafts include weaving of sleeping mats, sieves, and grain mats; woodcarving of spoons and wooden pieces used in necklaces; and the manufacturing of a variety of brass anklets and neck rings. Since precolonial times, Ndebele are believed to have obtained all pottery from trading with Sotho-speaking neighbors. The Tshabangu clan reportedly introduced the Ndebele to blacksmithing.

Trade

Archaeologists believe that societies such as that of the Ndebele formed part of the wider pre-nineteenth century trade industry on the African east coast and had been introduced to consumer goods such as tobacco, cloth, and glass beads. Historians such as Delius (1989) believe that a large number of firearms reached the Ndzundza-Ndebele during the middle 1800s.

Division of Labor

In a pastoral society such as that of the Ndebele, men attended to animal husbandry and women to horticultural and agricultural activities except when new fields ( amasimu ) are cleared with the help of men who join in a communal working party called an ijima. Even male social age status is defined in terms of husbandry activities: a boy who herds goats ( umsana wembuzana ), a boy who herds calves ( umsana wamakhonyana ), and so forth. Men are responsible for the construction and thatching of houses, women for plastering and painting of walls. Teenage girls are trained by their mothers in the art of smearing and painting. Even today girls from an early age (approximately 5 or 6) assist their mothers in the fetching of water and wood, making fire, and cooking. Female responsibilities have arduously increased in recent years with the increase in permanent and temporary male and female labor migrants to urban areas. It is calculated that some 80 percent of rural KwaNdebele residents are labor migrants.

Land Tenure

Land was tribal property; portions were allocated to individual families by the chief and headmen as custodians, under a system called ukulotjha , with the one-time payment of a fee that also implied allegiance to the political ruler of the area. Grazing land was entirely communal. The system of traditional tenure still applies in the former KwaN-debele, except in certain urban areas where private ownership has been introduced. In South Africa, Black people could never own land; the Ndzunzda-Ndebele's land was expropriated in 1883, when they became labor tenants on White-owned farms. Most Ndzunzda-Ndebele exchanged free labor for the right to build, plant, and keep a minimum of cattle. Since the formation of the KwaNdebele homeland, traditional tenure, controlled by the chief, has been reintroduced.

The last born son inherits the land, but married sons often build adjacent to their natal homesteads, if space allows it. In certain rural areas (e.g., Nebo), this form of extended three-generational settlement is still intact.

Kinship

Kin Groups and Descent.

On the macro level, Ndebele society is structured into approximately eighty patrilineal exogamous clans (izibongo ), each subdivided into a variety of subclans or patrilineages (iinanzelo or iikoro ). Totems of animals and objects are associated with each clan. The three- to four-generational lineage segment (i aro ) is of functional value in daily life (e.g., ritual and religion, socioeconomic reciprocity); it is composed of various residential units (homesteads) (imizi).

Kinship Terminology. Classificatory kinship applies, and with similar terms in every alternate generation—for example, grandfathers and grandsons (obaba omkhulu ). Smaller distinctions are drawn between own father (ubaba ), father's elder brothers (abasongwane ), and his younger brothers (obaba omncane ), although all these men on the same generation level may be called ubaba.

Marriage and Family

Marriage

Ndebele bridal dress. http://www.africamediaonline.com

Polygyny has almost disappeared. Bride-wealth consists of cattle and/or money (ikhazi ). Marital negotiations between the two sets of families are an extended process that includes the stadial presentation of six to eight cattle and may not be finally contracted until long after the birth of the first child.

Marital residence is virilocal, and new brides (omak jothi ) are involved in cooking, beadwork, and even the rearing of other small children of various households in the homestead. Brides have a lifelong obligation to observe the custom of ukuhlonipha or "respect" for their fathers-in-law (e.g., physical avoidance, first-name taboo).

Ndebele married women and unmarried women in the middle

A substitute wife (umngenandlu or ihlanzi ), in case of infertility, was still common in the 1960s. In case of divorce, witchcraft accusation, and even infidelity, a woman is forced to return to her natal homestead.

Currently, wealthy women with children often marry very late or stay single. Fathers demand more bride-wealth for educated women. Both urban and rural Ndebele weddings nowadays involve a customary ceremony (ngesikhethu ) as well as a Christian ceremony.

Ndebele Women in traditional Ndebele attire

Domestic Unit

The traditional Ndebele homestead (umuzi ), based on agnatic kinship and inter-generational ties, consists of several households. Apart from the nuclear household, the three-generational household along agnatic lines still seems to be the prevalent one among rural Ndebele.

Married sons of the founder household head still prefer to settle adjacent to the original homestead, provided that building space is available. A single household may be composed of a man, his wife and children (including children of an unmarried daughter), wives and children of his sons, and a father's widowed sister.

Inheritance

Although the inheritance of land and other movable and immovable household assets are negotiated within the homestead as a whole, Ndebele seem to subscribe to the custom of inheritance by the youngest son (the upetjhana ).

Socialization

The three-generational household enhances inter-generational contact; the absence of migrant mothers and fathers necessitates that grandparents care for children. Contemporary Ndebele households are essentially matrifocal, and children interact with their fathers and elder male siblings only over weekends.

Sociopolitical Organization

Social Organization

In precolonial times, Ndebele clan organization seemed to have been hierarchical in terms of duration of alliance to the ruling clans, Mahlangu for Ndzundza and Mabhena for the Manala. This pattern pervaded the entire political system.

Ndebele kid entering his house at Mpumalanga, South Africa

Political Organization

Tribal political power is in the hands of the ruling clan and royal lineage, Mgwezane Mahlangu (among the Ndzundza) and Somlokothwa Mabhena (among the Manala). In the case of the Ndzundza, the paramount (called Ingewenyama), the royal family, and the tribal council (ibandla ) together make political decisions to be implemented by regional headmen (amaduna or amakosana ) over a wide area, including the former KwaNdebele, rural areas outside KwaNdebele, and urban (township) areas. The headmen system includes more than one hundred such men of whom the greater portion are amakosana, or men of royal (clan) origin. Certain of these headmen were elevated to the status of subchiefs (amakosi ).

Give thanks and praise: Amasokana sing songs of praise, known as ukubongelela. (Oupa Nkosi, M&G)

There is currently a national political debate as to whether headmen, chiefs, paramounts, and kings like these will in future be stipended by local or central government.

Ndebele women

Social Control

Traditionally, criminal and civil jurisdiction were vested in the tribal court. The latter still presides over regional disputes (i.e., those relating to land, cattle and grazing, and bride-wealth). All other disputes are forwarded to local magistrates in three districts in the former KwaNdebele.

Conflict

Except for the 1800s, the Ndebele as a political entity were not involved in any major regional conflicts, especially after 1883, when they lost their independence and had their land expropriated. Almost a century later, in 1986, they experienced violent internal (regional) conflict when a minority vigilante movement called Imbokodo (Grinding Stone) took over the local police and security system and terrorized the entire former homeland.

In a surprising move, the whole population called on the royal house of Paramount Mabhoko for moral support, and, within weeks, the youth rid the area of that infamous organization. Royal leaders emerged as local heroes of the struggle.

Religious Beliefs.

In Ndebele religions, God, or the Supreme Being, uMlimu/Zimu is seen as the creator and sustainer of the universe in much the same manner as within Christianity. Ndebele uMlimu is believed to be active in the everyday lives of people, and even in politics. The more widely encompassing realm of the religious sphere compared to Western societies, as indicated by the central governing principle of traditional beliefs and practices. In general, people communicate with Zimu through the abezimu/amadhlozi (ancestral spirits) . These are the deceased ancestors.

Ndebele witch-doctor. http://www.africamediaonline.com/

Nineteenth-century evangelizing activities by the Berlin Mission did little to change traditional Ndebele religion, especially that of the Ndzundza. Although the Manala lived on the Wallmannsthal mission station from 1873, they were in frequent conflict with local missionaries. Recent Christian and African Christian church influences spread rapidly, however, and most Ndebele are now members of the Zion Christian Church (ZCC), one of a variety of (African) Apostolic churches, or the Catholic church. Traditional beliefs were centered on a creator god, Zimu, and ancestral spirits ( abezimu ).

Ndebele people

Religious Practitioners

Disgruntled ancestral spirits cause illness, misfortune, and death. Traditional practitioners ( iinyanga and izangoma ) act as mediators between the past and present world and are still frequently consulted.

Sorcerers (abathakathi or abaloyi) are believe to use familiars like the well-known "baboon" midget ( utikoloshe ), especially in cases of jealousy toward achievers in the community in general. Both women and men become healers after a prolonged period of internship with existing practitioners.

Ndebele woman

Ceremonies

Initiation at puberty dominates ritual life in Ndebele society. Girls' initiation ( iqhude or ukuthombisa ) is organized on an individual basis, within the homestead.

It entails the isolation of a girl after her second or third menstruation in an existing house in the homestead, which is prepared by her mother. The weeklong period of isolation ends over the weekend, when as many as two hundred relatives, friends, and neighbors attend the coming-out ritual.

The occasion is marked by the slaughtering of cows and goats, cooking and drinking of traditional beer ( unotlhabalala ), song and dance, and the large-scale presentation of gifts (clothing and toiletries) to the initiate's mother and rather. In return, the initiate's mother presents large quantities of bread and jam to attendants. The notion of reciprocity is prominent. During the iqhude, women sing, dance, and display traditional costumes as the men remain spatially isolated from the courtyard in front of the homestead.

Male initiation ( ingoma or ukuwela ), which includes circumcision, is a collective and quadrennial ritual that lasts two months during the winter (April to June). The notion of cyclical regimentation is prominent: initiates in the postliminal stage receive a regimental name from the paramount, and it is this name with which an Ndebele man identifies himself for life.

Ndebele initiation (ukuya eNgomeni) from being a boy to being a man is a complex and involved process. Him and his fellow initiates (Amasokana) were away for 3 months in the blistering cold going through whatever it was they are taught in the bush (women and non-initiated men are forbidden from knowing what goes on there).

The Ndzundza-Ndebele have a system of fifteen such names that are used over a period of approximately sixty years. The cycle repeats itself in strict chronological order. The Manala-Ndebele have thirteen names.

Ndebele male initiates

The numerical dimension of Ndebele male initiation is unparalleled in southern Africa. During the 1985 initiation, some 10,000 young men were initiated and, during 1993, more than 12,000. The ritual is controlled, installed, officiated, and administered by the royal house.

Young Ndebele men have just finished their initiation stint wherein they were interned for two months and learning the responsibilities of a man.

It is decentralized over a wide area within the former KwaNdebele, in rural as well as urban (township) areas. Regional headmen (see "Political Organization") are assigned to supervise the entire ritual process over the two-month period, which involves nine sectional rituals at emphadwini (lodges in the field) and emzini (lodges at the homestead).

Ndebele bearded wear

Arts

Ndebele aesthetic expression in the form of mural art and beadwork has won international fame for that society during the latter half of the twentieth century. Mural painting ( ukugwala ) is done by women and their daughters and entails the multicolor application of acrylic paint on entire outer and inner courtyard and house walls.

Ndebele beadwork. http://www.africamediaonline.com/

Earlier paints were manufactured and mixed from natural material such as clay, plant pulp, ash, and cow dung. Since the 1950s, mural patterns have shown clear urban and Western influences. Consumer goods (e.g., razor blades), urban architecture (e.g., gables, lampposts), and symbols of modern transportation (e.g., airplanes, number plates) acted as inspiration for women artists.

Beadwork ( ukupothela ) also proliferated during the 1950s; it shows similarity in color and design to murals. Ndebele beadwork is essentially part of female ceremonial costume. Beads are sown on goat skins, canvas, and even hard board nowadays, and worn as aprons. Beaded necklaces and arm and neck rings form part of the outfit that is worn during rituals such as initiation and weddings.

As Ndebele beadwork became one of the most popular curio art commodities in the period from the mid-1960s to the mid-1990s, women also beaded glass bottles, gourds, and animal horns. The recent prolific trading in Ndebele beadwork concentrates on "antique" garments as pieces of art. Some women are privately commissioned to apply their painting on canvas, shopping center walls, and even cars.

Car decorated with Ndebele paintings in Pretoria, South Africa.

The recent discourse on Ndebele art suggests that the phenomenon should be interpreted in terms of the conscious establishment of a distinctive ethnic Ndebele niche at a time in South African history when the Ndebele struggled to regain their land and were not regarded as a society with its own identity.

Medicine

Current medical assistance includes the simultaneous use and application of traditional cures and medicines and visits to local hospitals and clinics. Children are born with or without the assistance of modern maternity care.

Death and Afterlife

Death is attributed to both natural and supernatural causes. A period of night watch over the body precedes the funeral. Funerals reunite the homestead and family members and involve the recital of clan praises ( iibongo ) at the grave and the slaughtering of animals at the deceased's homestead afterward. Today many Ndebele receive church burials. Widows are regarded as unclean; they may be ritually cleansed after many months or even a year. Traditionally, the deceased are buried at family grave sites, which are usually at the ruins of previous settlements and often far away from their homes. Nowadays, however, people are mostly buried at nearby cemeteries.

source:http://www.encyclopedia.com/topic/Ndebele.aspx

Initiation School Amongst the Southern Ndebele People of South Africa: Depreciating Tradition or Appreciating Treasure?

By Linda van Rooyen*, Ferdinand Potgieter and Lydia Mtezuka

Faculty of Education, University of Pretoria, South Africa

Initiation in Southern Ndebele culture

Initiation, bush school or secret society in Southern Ndebele culture refers to the secretive and closed preparation of the young teenager for adulthood. This type of school is presented in a single block and mainly serves as the child's transit-education during which he or she progresses from childhood to adulthood. "It denotes a body of rituals that marks the passage from one stage of development to another" (Mabena, 1999, p. 24; Fowler and Fowler, 1972, p. 527; Mbiti, 1971, p. 94; Rooth, 1984, p. 69; Monroe, 1957, p. 3). The literature also refers to oral teachings of which the purpose is to exert a pertinent influence on, and

produce a decisive alteration in the social status of the candidate to be initiated (Bozongwana, 1983, p. 29; Mabena, 1999, p. 12; Snoek, 1987, p. 101).

According to these scholars and against the Rites of Passage presented by Van Gennep, the initiation school

of the Southern Ndebele people may best be understood under the following subheadings;

Ndebele male initiates

1. Initiation as severance and separation

The phase of severance and separation (Van Gennep) can be described as the first phase of the secretive and closed process of initiation that takes place when a young person is prepared for adulthood. During this phase, the young person has to "dissociate" and '"disjoin" (Kritzinger, Steyn, Schoonees and Cronje, 1970, p. 316) him or herself from a childlike lifestyle and identity. This severance or abstraction is not a superficial

or partial detachment, but a rather intense process that involves the total person (intellectual, psychological, social, emotional, spiritual, etc. [Mtezuka, 1995, p. 67]).

During the isolation, the child has to progress from an "old self" to a "new I" with a new identity and a new role to fulfil. The child becomes a new person and at first, a stranger to him or herself. Based on the principle

that through abstraction comes clarity, the child, during the process of isolation, has to master the developmental task of altering his or her self-concept and the way he or she thinks about it.

1.1 The phase of severance and isolation as part of the Southern

Ndebele initiation - an introduction

Both boys and girls, ranging from twelve to twenty years of age, undergo initiation. Initiation is also offered to

adolescents who are about to marry and have not yet attended any initiation school. Unless the child has attended a state school (which is compulsory in South Africa), he or she had very little formal schooling up to the point that he or she goes to initiation school. In the traditional setting, there are no teachers or tutors specially employed to assist with the education of the children and no schools or special places that are set aside for learning.

Traditional children learn by being around and imitating their parents and other adults. They also learn through experience and as such gradually learn to exercise control over their behaviour on their own. By letting the children assume responsibility and by making them, as members of a larger group, responsible

for the performing of certain tasks, their own behaviour and the behaviour of their peers, the "system" contributes to the education of the child (Makopo, 11 July 1995, interview).

The young boy is generally regarded as relatively unimportant, an undignified member of his family, not

united with his soul, and, consequently, "not really human". He is therefore relatively free to do as he pleases (up to the point of going to initiation school), and any form of misbehaviour, even theft, is not condoned from a young boy (Makopo, 11 July 1995, interview). Before going to the initiation school, boys are called "umsogwabo", a term which refers to their insignificant status. The attire for the insignificant is referred to as "amabetshu" and the basic item of clothing to reveal their "inferior status" is a front apron, made from a goat's skin to which they can add any number of decorative items (either borrowed from their sisters or friends such as decorative badges or pieces of headwork made by their mothers or sisters) (Mphahlele, 1992, p. 9).

The initiation ceremonies for boys are known as "wela" and those for girls, "ukuthomba" and "uqude" (first and final stage). The boys and young men who have been chosen and are ready for initiation are referred to as "amaja". They are differentiated from other boys or young men by hornlike structures made out of grass and reed ("umshojo"), which are placed on their foreheads for a period of a month, prior to initiation. The age of initiates is regarded as very important. It confers economic and social privileges, primarily as far as

the distribution of game, rewards and wealth is concerned.

Otterbein (1969, p. 118) states that the exact age for initiation among African cultures cannot be determined, as this differs from culture to culture. He maintains, however, that generally speaking, initiation takes place between ages ten to twenty years. Ntombeni (2005, p. interview) however emphasized that the girls rarely start menstruating before the age of thirteen years and therefore only start their initiation when they are thirteen years of age. The first menstruation and the first ceremony are referred to as "ukuthomba".

During the isolation, each initiate receives a new name, different from the one given to him or her at birth, a

symbolic indication that he or she has entered a different developmental stage with a different, new identity.

1.2 Time and place of isolation

The isolation of boys takes place between April and June, always in wintertime when there is less risk for their wounds to become septic. The boys spend the time of isolation in a secluded and special rural camp, always under the supervision of an elder, appointed by the chief. Temporary grass shelters, hidden by bushes or trees, are erected, preferably on hilltops outside the village or in the mountains.

As mentioned above (par. 1.1), the isolation of the girls only takes place after she has started her first menstruation.

Traditional Southern Ndebele girls seem to have a close relationship with their mothers and are expected to report everything that happens to them, to their mothers (Mtezuka, 1995, p. 66; Ntombeni, 2005, interview). This includes the requirement that when a girl menstruates for the first time, she has to inform her mother, who will inform her father. The mothers and sisters, as well as the elderly women of the closest family will also be informed, so that they can become involved in the applicable ceremonies.

During her isolation she is kept at home (except for the "washing" which takes place at the river) or after the final stage when she and the other young girls gather for a feast at a demarcated place.

1.3 Duration of isolation

The duration of the isolation differ between cultures. Among Southern Ndebele the ceremonial training of the

boys is completed within two to three months. The duration usually depends on the healing process after the "cutting" or surgery (circumcision). Child (1993, p. 149) describes that circumcision takes place on the second day at the initiation school and that the healing has taken place satisfactorily by the end of the ceremony, about two to three months thereafter.

Southern Ndebele girls are not circumsized. There are two isolation periods for girls. The first period lasts from between five to ten days for the first menstruation or menarche and the second stage, referred to as "uqude", follows, which lasts for two to three months (Makopo 11 July 2002; interview). This second period of isolation is usually held after the second or third menses. The girl is kept in her mother's but or in one of the rooms in the house, depending on the size of the house "and her father's wealth" (Mtezuka, 1995, p. 55). She is kept in isolation for a period of eight weeks. "During this period, she is not to be seen by anybody besides her mother and aunts" (Mtezuka, 1995, p. 55). It seems as if a lateral system of authority prevails as the aunts are closely involved, not only in the rather private matters of the girls' growing-up, but also in

the general disciplining of the young girl.

2. Initiation as threshold, restoration and entrance

Van Gennep describes the second phase in his Rites of Passage as that of threshold, restoration and entrance. The concept "thresholding" was originally used to refer to the piece of timber or stone which lies beneath the bottom of a door (the sill of a doorway); hence, the entrance to a house or building (Emery and Brewster, 1948, p. 1985). With regards to the initiation of a young person the concept "threshold" refers to that period when a young person, in his or her state of isolation, while being in a confined, isolated space, consciously lingers on the threshold of, or in the "great divide" between childhood and adulthood.

It is during this period of thresholding, before the young person takes the plunge into a new developmental phase with a new identity, that the actual restoration (Van Gennep, 1909) (to bring back to a former, original, or normal condition; to reinstate in dignity" [Emery and Brewster, 1948, p. 1540]) and preparation

(Van Gennep, 1909) ("to put in due condition by training or instruction" [Emery and Brewster, 1948, p. 1383]) of the young person for adult life, take place.

2.1 Restoration, preparation and entrance of

(a) the Southern Ndebele girl

It is during this phase, while in isolation and waiting on the threshold of life, that the young girl undergoes her restoration. She is mainly tutored on the secrets of womanhood. These teachings include aspects such as the rules of hygiene and privacy, advice with regard to sexuality, childbirth, health, married life, on how to be a good and loving mother, and the best honoured wife. Self-respect and self-discipline (Makopo, 11 July 2002, interview) and submissiveness (Ntombeni, 2005, interview) are highly valued and expected of the girl. She also learns the appropriate feminine behaviour as observed by the group, e.g., the correct use of the left and the right hand when eating (the right hand is used for lifting food to the mouth and therefore, at all times, has to be kept clean) (Ntombeni, 2005, interview).

The teachings include lectures on sexuality and relationships with members of the opposite sex. She will be allowed to be friends with boys, to receive visits and to go out with them, but is warned not to be tempted to partake in sexual actions, "viz caressing as it can lead to sexual intercourse" (Mtezuka, 1995, p. 42). Although no internal intercourse is allowed the girl is encouraged to have external intercourse as it is believed not to be "dangerous". By "'external intercourse" it is understood that a man is not allowed to ejaculate inside the female's body- ejaculation is to be done outside the vagina, thus "external intercourse". The girl is warned that, should she conceive a child before marriage, as a form of punishment she will be forced to marry a

widower, the oldest man in the village or community, or a man with many wives where she will have the lowest status (Makopo, 11 July 2002, interview).

On a question about the prevention of HIV/AIDS, Ntombeni (2005, interview) remarked that she heard about it and that '"it is sad" but that she, as an elder, can't do anything to prevent the youth from being infected.

On the last day of her isolation the young girl will make a symbolic "entrance" into the outside world. Her girl

friends will start to dance and sing outside the hut, early in the evening until the following morning when she will appear and they will accompany her, singing and dancing, to the river ("emlangeni") where she must be washed and "purified". The girl is literally washed in the river to make the '"dirt" flow downstream and away and she "becomes" the new person, prepared and restored, with a new identity (Mtezuka, 1995, p. 39).

(b) the Southern Ndebele boy

Boys grow up with the knowledge that they have to identify themselves with their own peer group ("undangani") until the "time comes" for them to go to initiation school and, after that, to get married (Mphahlele, 1992, p. 44).

It is culturally and traditionally determined that the boy cannot marry until he has successfully completed initiation school. But after completing initiation school, the boy has to get married. The family would suggest that, if there is a brother in the group that has recently completed initiation school,

he must marry before the next brother is sent to initiation school. If he fails to get married within four years of

completion, his parents together with his school teachers have to choose a wife for him.

Ndebele initiates

It is only through initiation (in the phase of thresholding) that the Southern Ndebele boys are able to learn the

definition of and identification with the male role maintained by the organized adult males and to view the wall from the male adult's point of view. Not all the initiates succeed in passing through this rigorous period, in some instances some young men actually die (Ntombeni, 2005, interview). The survivors of the initiation period are considered to have proved themselves worthy of rejoining society as responsible and worthy adults. The initiates experience a considerable amount of social pressure to succeed and pass through the

period of transition and transformation (restoration): i.e. the rebirth of the person with a new identity. To symbolise the break with the past, all the objects used ("wela") during the ceremony are burnt and while the fires rage, a feast is held; a celebration to manhood!

Unlike girls, boys are taken out of the village to a chosen place only known to the males of that community (in this regard also refer to par. 1). Boys attend initiation school for three to four months, staying there until they have completed the course, together with their teachers.

During the restoration and preparation, the boys are tutored on bodily changes, their relationship with members of the opposite sex, e.g., the importance of not having internal intercourse until after they got married and their roles as fathers and marriage partners. As part of their social education (also refer to the par. The social preparation of the child, p. 24), the initiates inter alia learn to honour the chief and tribal custom, respect those older than themselves, value those things which are of value to the society and to

observe tribal taboos, especially those connected with food and their sexual life.

Initiation is a period during which the individual is continuously being tested and invariably even the best

effort is judged by the supervisors of the initiation to be inadequate and deserving of a beating. The hardships that are endured by male initiates, such as standing in freezing rivers for hours, carrying burning coals and eating stale food are all aimed at teaching the initiates the correct behaviour that their society will expect of them, such as being humble and respectful to their elders. While undergoing these hardships they gain an appreciation for the values and comforts of society and can't wait to rejoin their families to take up their new roles.

Circumcision of boys as a symbol of their preparation for life

The initiates must be humble and respectful to all and have to use the special terms characteristic of the school whenever they speak. The initiates are highly secretive of the content of initiation, they are told not to disclose information. Child (1993, p. 149) cited that the initiates seem clearly aware of the critical meaning of the ceremony as a turning point in their lives. On the one hand they fear the danger of castration or death from circumcision, but on the other hand, they experience the absolute necessity of taking part, in order to shift from one mode of life to another. Both the initiates who were interviewed stated clearly that they do not see the so-called value of initiation schools and do not understand all the fuss made about the ceremony of

initiation. The boys stated that, if they had a choice, they would certainly not agree to go to the initiation school (Initiate X, interview, Initiate Y, interview).

Young men of the Ndebele tribe in South Africa participate in an initiation ceremony – Image Invisionfree

The identity of the person performing the circumcision is kept a secret; it could be a magician, a witchdoctor or an elderly member of the village chosen by the chief. During an interview (Mahlangu, 2004, interview) the following statement was made; "whatever happens at initiation, it must not be discussed or revealed to anybody who has never undergone such training".

It is believed that the foreskin of the penis is removed by cutting it with a sharp knife. This is to be done without an anesthetic on the first day of initiation. It is to be done in secret, which in most cases, is out in the veld. After cutting, the wound is not covered, but has to be dressed regularly by a mixture of medicines prepared by the village's witchdoctor to avoid it becoming septic. The boy's body is smeared with ash to identify him as an initiate.